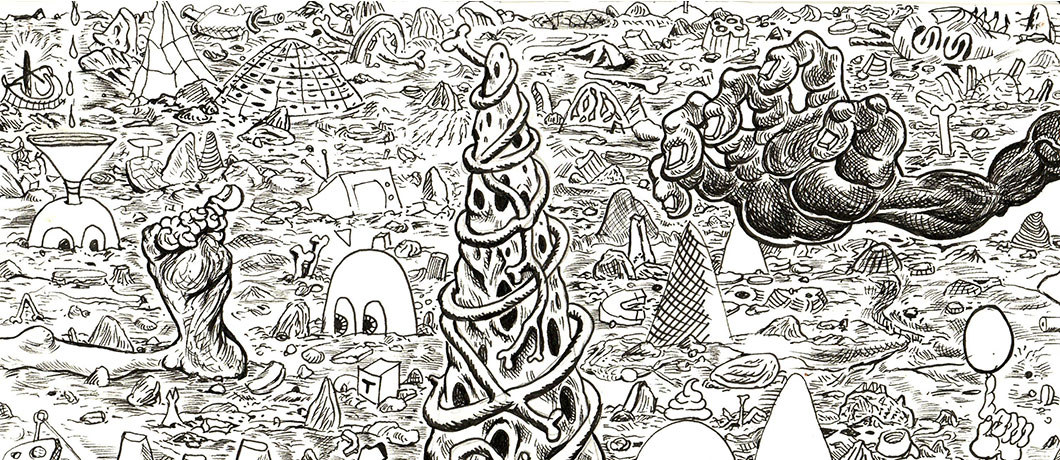

IMAGE ABOVE: Trenton Doyle Hancock. Cave Scape #3, 2010. Ink on paper, 6 ¼ x 10 inches. Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York.

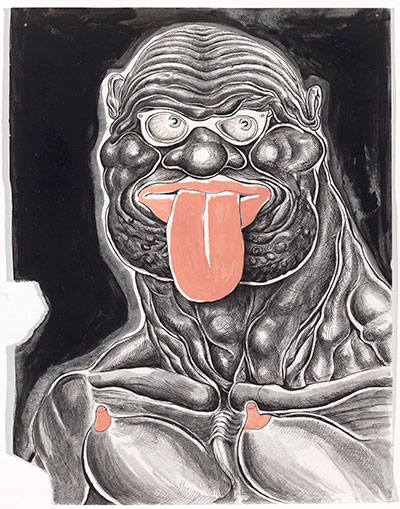

Self-Portrait with Tongue, 2010

Acrylic, mixed media on paper

16 x 13 ½ inches

Courtesy the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York

Any daydreamer remembers being back in school, either ignoring the teacher or absorbing the world around them as they doodled in the margins of their notes. From superheroes to band names, those drawings and their subjects come to mind more quickly than the school lessons that influenced them. Teachers often think of them as slackers, and sometimes they are, but once in a while one of those “slackers” is developing something deeper. Organized by Senior Curator Valerie Cassel Oliver, Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing gives CAMH visitors an in-depth look into the development of Hancock’s style by showcasing works dating back to when he was 10 years old.

This is not to say that Hancock was ever a slacker, although, as Brian Droitcour wrote in “Young Incorporated America,” his recent Art in America article, “The slacker or the loser, the hacker and the user—these are some of the bodies making meaningful art now.” With over 200 works on display, it’s clear that Hancock has an ability to daydream reserved for only the most creative of artists.

Rather than a chronological display, Cassel Oliver has separated the works into five thematic sections. Central to the exhibition, literally and figuratively, is Moundish. The vulgar, adorable, and disturbing series includes drawings associated with the narrative of the Mounds, fictional creatures propagated by the ejaculation of an ape man in a field, as well as the destructive force of their world: the Vegans. In a fashion both comic and graphic, the narrative shows struggles with birth, life, death, jealousy, good, and evil.

Epidemic and The Liminal Room are two free-standing sections dedicated to stand-alone work and ephemera that showcase the artist’s development in two very different manners. While The Liminal Room explores Hancock’s experimentation with drawing, Epidemic gives viewers a look back at comics from his college days and other early sketches, and debuts a new series entitled Step and Screw.

An examination of self-inclusion in art, From the Mirror allows a view into the artist’s mindset throughout the artistic process. Whether intentional or subconscious, we view the world and create works through ourselves. This section showcases Hancock’s interpretation of himself over the past two decades through an exploration into the various forms of portraiture that he has used.

The final section, The Studio Floor, is a series of ten drawings. In Hancock’s mind, these represent the catalyst of graphic narratives into his art practice, bringing his daydreams to life without ever losing sight of the issues. For others, it’s a reminder that school-age daydreamers might find their passion outside of the classroom.

—MICHAEL MCFADDEN

Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston

Through Aug. 3