The scene is the summer of 2020. The country is in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Protestors are outraged by the murder of George Floyd and other Black men at the hands of the police. A raucous presidential election has split the country into two hard camps.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth curators were also planning their exhibition schedule. The associate curator of photographs, Kristen Gaylord, recently acquired nearly 250 vernacular photographs of Black Americans from Peter Cohen, a prolific collector of the medium based in New York City.

Gaylord said the photographs of Black Americans filled a gap in the museum’s esteemed photography collection. So, she pitched the idea of a show challenging viewers to examine how Black life is, and isn’t, portrayed in the arts using the new acquisitions. That show, Black Every Day: Photographs from the Carter Collection, co-curated with the University of North Texas Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Art and Design Studies Lauren Cross, whose artistic, curatorial and scholarly interests include Black representation, on view June 11-Sept. 11.

“Black Every Day shows Black people living as Black people every day,” Gaylord said. “Not just on trauma days. Not just on holidays. But also looking at the ‘Black everyday.’ What does everyday life look like? And why don’t we depict that more often in institutions?”

“One could assume that with these vernacular photographs, many of them could have been taken by Black people, outside of maybe the more portrait-like, professional photographs. But we don’t know,” Cross said.

That assumption also weaves itself into one of the biggest arguments among curators and scholars of photography. Are vernacular photographs still considered collectible and valuable just because a star photographer took them? Someone, after all, took them.

1 ⁄9

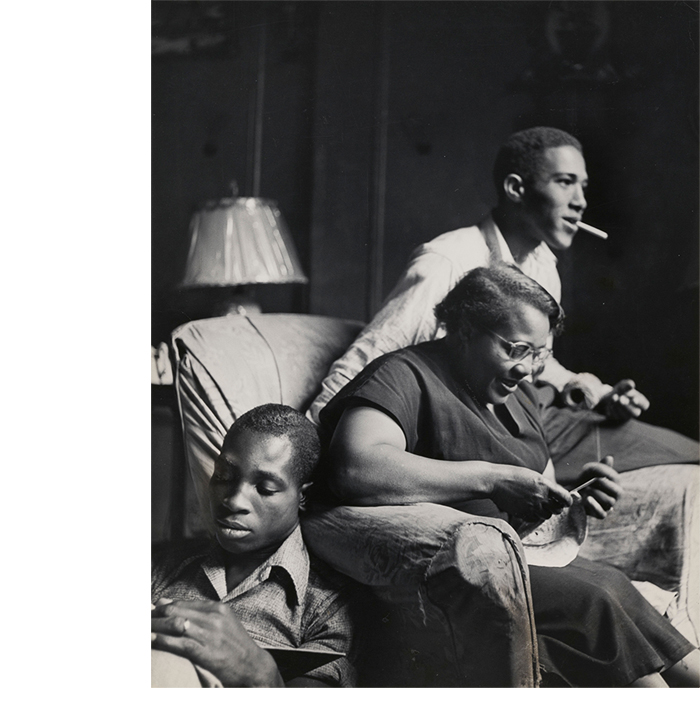

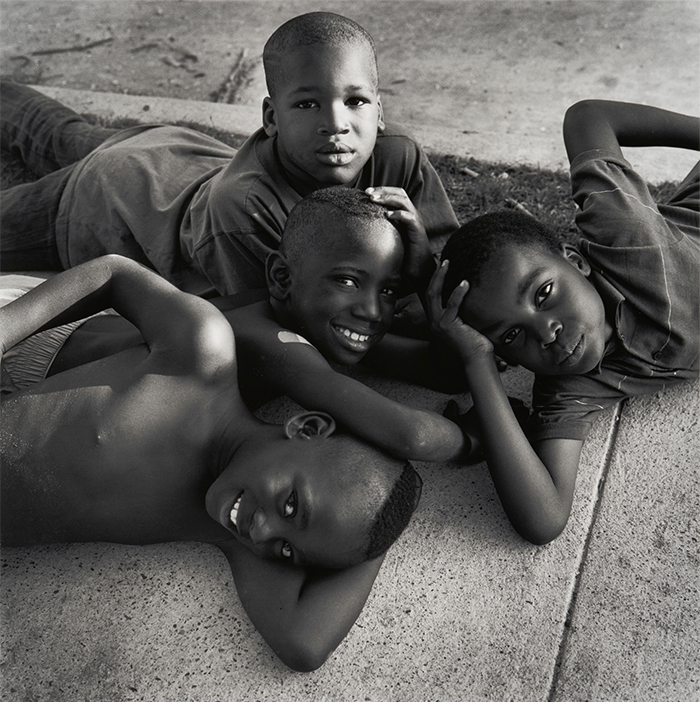

Gordon Parks (1912–2006), Red Jackson with His Mother and Brother, Harlem, New York, 1948, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1998.33, © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

2 ⁄9

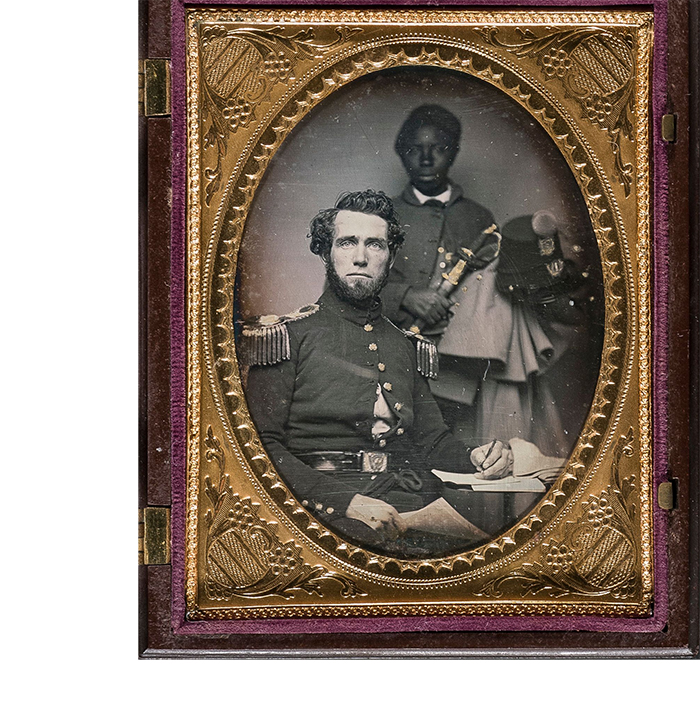

Sheldon K. Nichols (active ca. 1850–1854), [Untitled], ca. 1851, daguerreotype with applied color, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1986.9

3 ⁄9

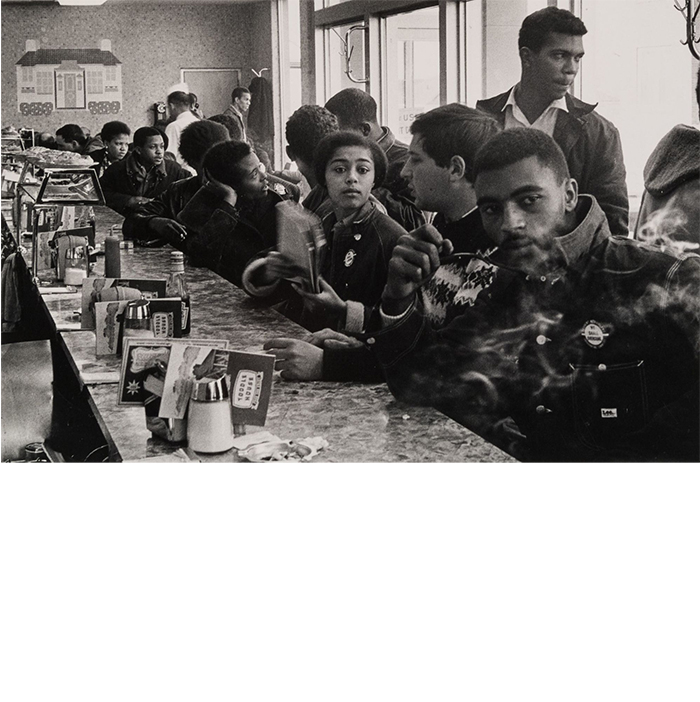

Danny Lyon (b. 1942), Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Sit-In, Atlanta, 1963, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1997.30, © Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos.

4 ⁄9

Earlie Hudnall, Jr. (b. 1946), Wheels, 1993, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P1997.19, © 2012 Earlie Hudnall, Jr.

5 ⁄9

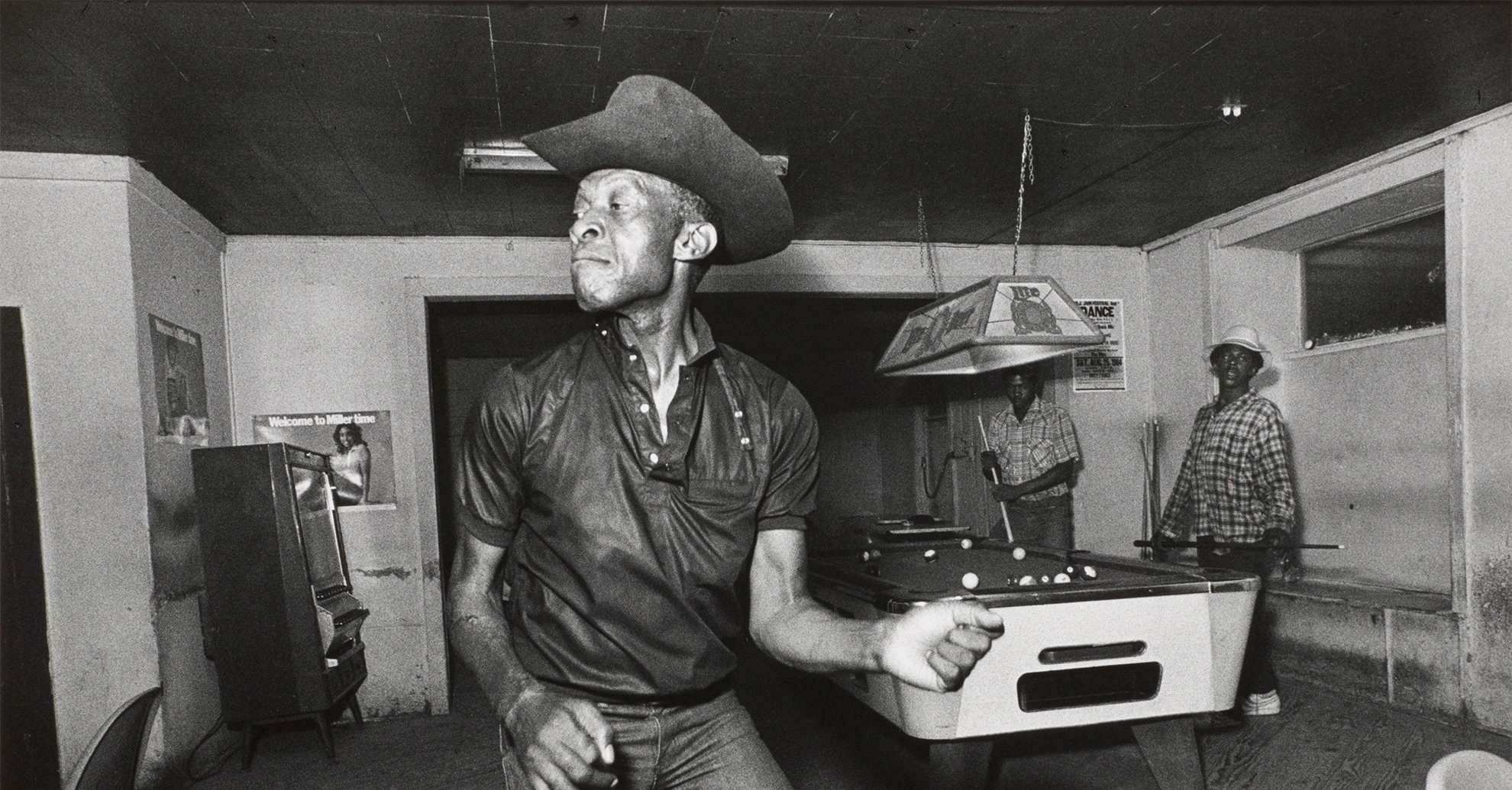

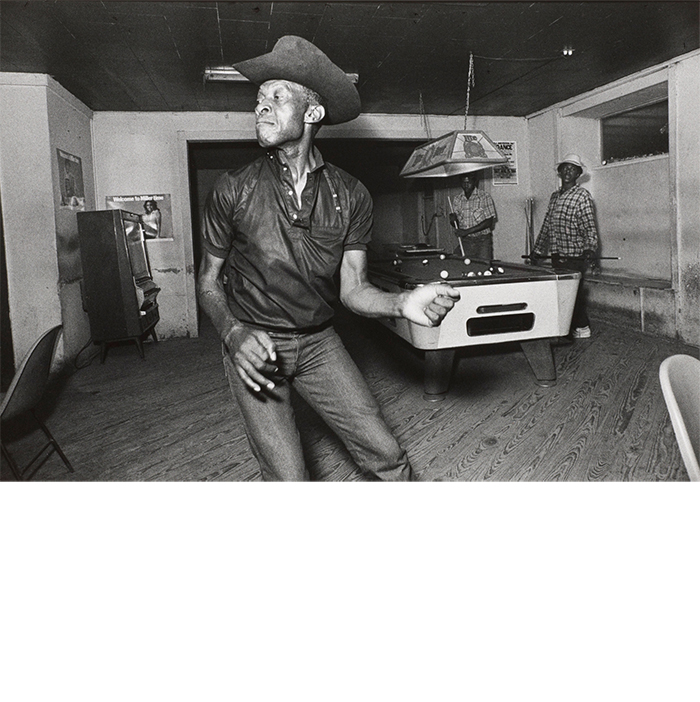

Fred Baldwin (1929–2021) and Wendy Watriss (b. 1943), Saturday Night, 1984, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of the Texas Historical Foundation with support from a major grant from the DuPont Company and Conoco, its energy subsidiary, and assistance from the Texas Commission on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts, P1985.17.20, © 1984 Wendy V. Watriss

6 ⁄9

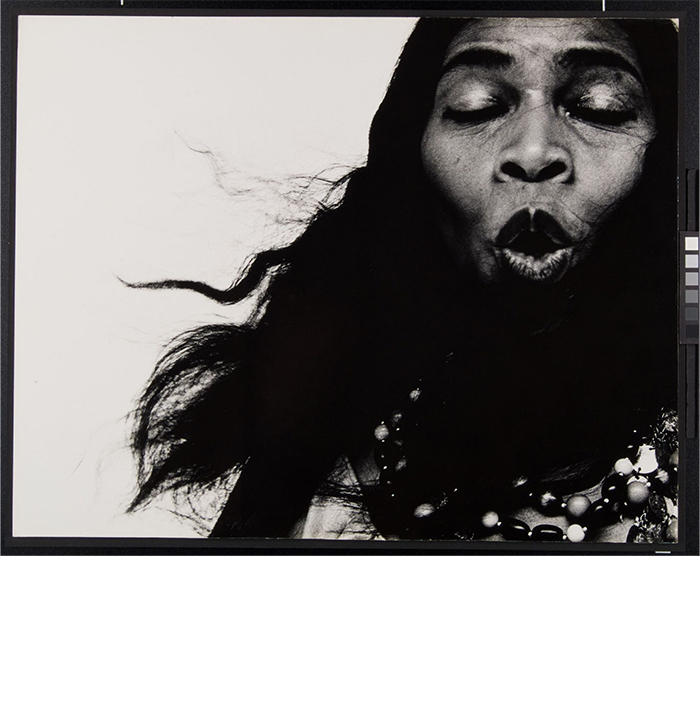

Richard Avedon (1923–2004), Marian Anderson, 1955, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of Edward L. Mattil, P1990.25, © The Richard Avedon Foundation.

7 ⁄9

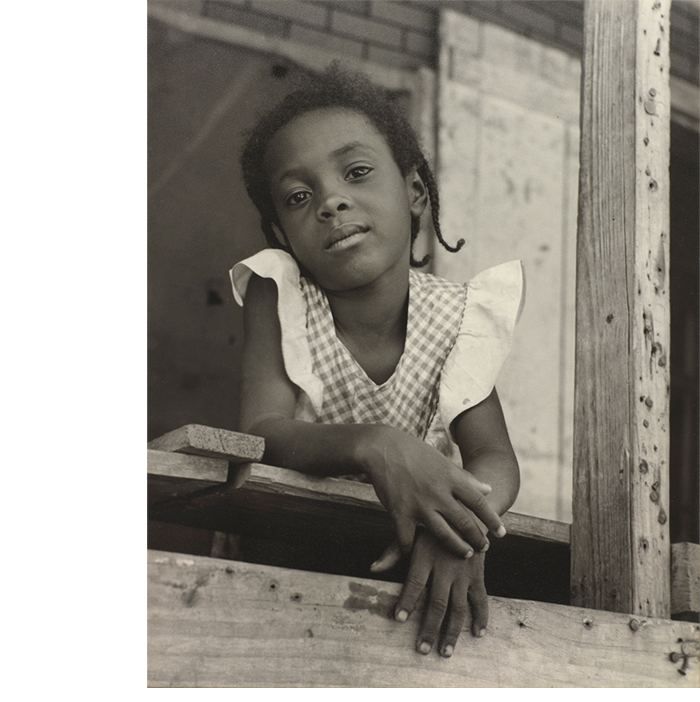

Carlotta M. Corpron (1901–1988), Delores, Melrose Plantation, Louisiana, 1950, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of the Dorothea Leonhardt Fund of the Communities Foundation of Texas, Inc., P1985.2.33, © 1988 Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

8 ⁄9

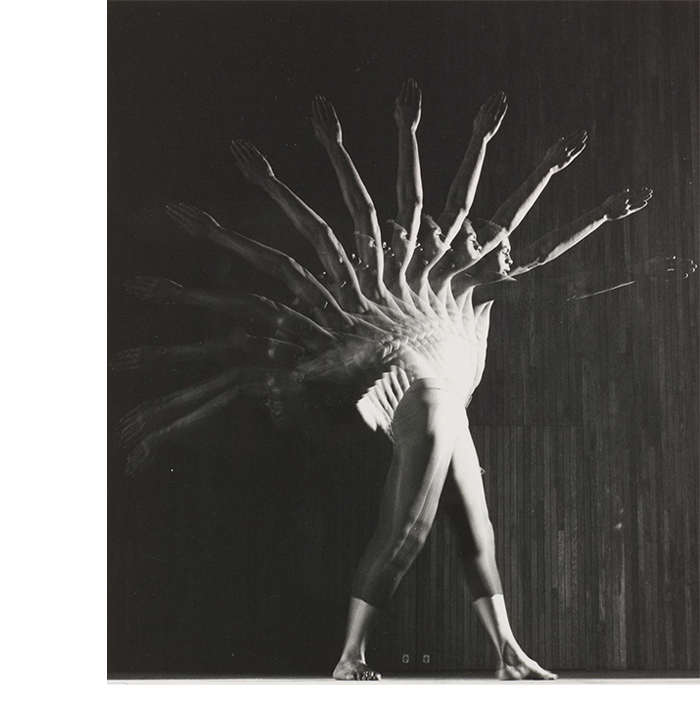

Harold Eugene Edgerton (1903–1990), [Gus Solomons], ca. 1960, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Gus Kayafas, Concord, Massachusetts, P1991.32.9, © Estate of Harold E. Edgerton, courtesy Palm Press, Inc.

9 ⁄9

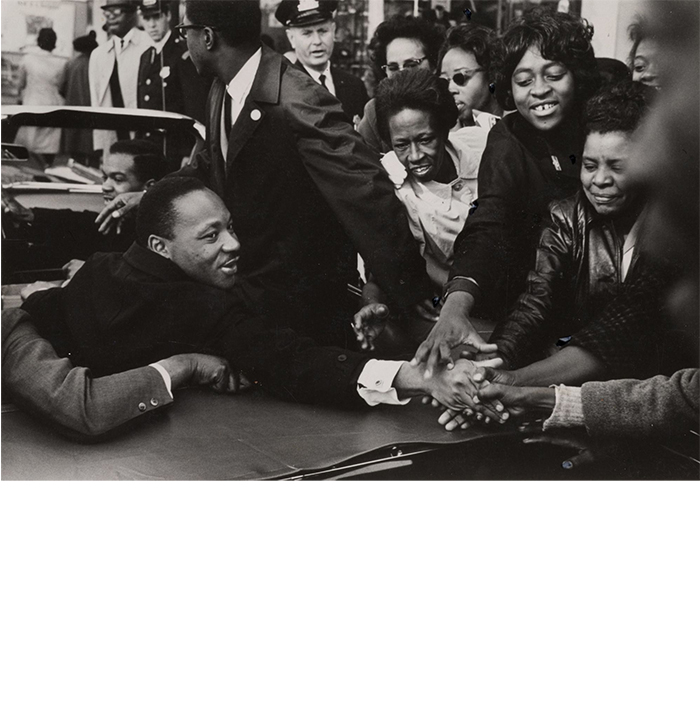

Leonard Freed (1929–2006), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., after nomination for Nobel Peace Prize, Baltimore, Maryland, 1964, gelatin silver print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Gift of Brigitte Freed, P2019.104, © Leonard Freed – Magnum – Brigitte Freed.

The exhibition opens with one of those contested photographs, also the oldest in the show: a daguerreotype by Sheldon K. Nichols circa 1851.

The image “stopped me in my tracks,” Cross said. The subject’s eyes and expression are so complex.

“I was like, ‘Is he about to cry? Is he kind of a little proud to be in the image? And you know, it’s hard to tell. And as we’re talking about, ‘what is it? What is it like to be Black every day like that?’ That image for me was like, ‘Whoa, like, it’s complicated.’”

These celebratory moments are an act of resistance within themselves, Cross said. “What are they resisting against? They’re resisting that type of experience of being locked in. They resist being completely prevented from celebrating, being joyful, and worshiping—all these things.”

—JAMES RUSSELL