Review: Utopia/Dystopia: Construction and Destruction in Photography and Collage

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

March 11-June 10

www.mfah.org

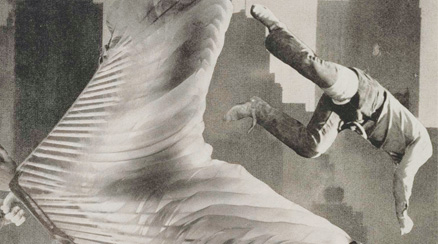

A woman in a white dress her lower half anyway, floats dreamily against the backdrop of a hazy Manhattan skyline; her head and torso eclipsed by a giant bird’s feather, from which a pair of pistol-wielding human hands spring. Meanwhile, the headless body of man plummets past the skyscrapers to a sure demise, inevitably conjuring up thoughts of 9-11.

But, the montage A Trait Angel, which Japanese artist Okanoue Toshiko created with fragments from American magazines such as Life and Vogue, dates to 1955, when postwar Japan remained subject to the cultural and political dominance of the United States. Okanoue’s juxtaposition of fantasies with nightmares strikes a conflicted mood that pervades much of the group show Utopia/Dystopia: Construction and Destruction in Photography and Collage.

As the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston’s contribution to FotoFest, Utopia/Dystopia smartly connects the basic activity of photo-based collage cutting and pasting found or captured images to create new ones with artists’ impulse to dream up imaginary societies and places, both hopeful and disturbing.

Featuring historical figures such as Hannah Hoch and László Moholy-Nagy alongside contemporary artists like Vik Muniz and Wangechi Mutu, the show grew out of assistant photography curator Yasufumi Nakamori’s desire to present Okanoue’s work in a transnational context with Berlin Dadaist John Heartfield’s scathingly satirical 1930’s photomontages that warned of the coming fascist dystopia. (The international mix includes Houston artists John Sparagana and Dana Harper, who use appropriated magazine imagery to distinct ends, and Josh Bernstein, who weaves photography into a mixed-media retelling of a 16th-century colonial explorer’s memoir.)

It’s a context that spans most of the history of photography and encompasses practices approaches ranging from constructivism to conceptualism and even commercialism: In 1893, Ezaki Reiji, a Tokyo studio photographer, combined his portraits of as many as 1,700 infants in Collage of Babies, an advertisement for his business that seemingly foresaw the city’s continued economic and population growth.

Nakamori likens Ezaki’s early depiction of an “anticipated utopia” through “the selection of images from a seemingly endless source” to Joel Lederer’s digital photos of landscapes in Second Life, an online virtual world in which users create and share virtual property. An image from Lederer’s The Metaverse is Beautiful series has the cheesy luminosity of a Thomas Kinkade painting. Given Second Life leaseholders’ ability to montage landscapes from memories and found images, Kinkade may well have inspired Lederer’s appropriated kitschscape.

Using appropriation more pointedly, works from Martha Rosler’s powerful Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful series (1967-72) juxtapose images from lifestyle magazines with found Vietnam War photography to wrench a distant, all-too-real dystopia into the living rooms of middle-class Americans. The chairs in Patio View, a recent MFAH acquisition, look onto a Vietnamese cityscape that has been laid to waste by American bombs.

In one of Nakamori’s own uncanny juxtapositions, Rosler’s montage hangs alongside El Lissitzky’s surreal 1929 portrait of Russian avant-garde filmmaker Dziga Vertov, whose head fills the iris of a giant eye, along with a caption bearing Vertov’s chilling aphorism: “In the face of the machine we are ashamed of man’s inability to control himself.”

– DEVON BRITT-DARBY

The former art critic for the Houston Chronicle, Devon Britt-Darby is an artist and freelance writer.