Standing by the Rags, nurse 1988-89

Tate: Purchased with assistance from the Art Fund, the friends of the Tate Gallery and anonymous donors 1990 © The Lucian Freud Archive. Courtesy Lucian Freud Archive.

Lucian Freud and Omer Fast in North Texas

I didn’t exactly want to drive four-and-a-half hours to see Lucian Freud Portraits at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. “Felt strangely compelled” is more like it, since the German-born British artist’s labor-intensive paintings of “people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know,” are nothing if not strangely compelling. All that pale, sagging, unsparingly observed flesh rendered, at times, with an over-the-top tactility – it’s one thing to know you won’t be able to turn away when you’re standing in front of it; it’s another to make a mini-pilgrimage for a case of the willies.

Still, what willies they are, induced by an artist who, as the Modern’s chief curator Michael Auping writes in the show’s terrific catalogue, Freud strove to shrink the distance between viewers and his sitters and to dive “into the intricacies of flesh, … imparting a visceral facture to the skin of his subjects.”

Though we don’t always know Freud’s sitters’ names or their relationship to him, we can be sure he knew them well, since he took months, sometimes years, to finish a painting. (Freud, who died last year at 88, was known to work eight to 10 hours a day, seven days a week, with several paintings going at once.) One sitter, art critic Martin Gayford, wrote in his diary that he was spending more time with Freud than anyone but his wife and children – “and more time just talking than with anyone at all” – as he sat seven months for a modest-size head-and-shoulders portrait.

Freud even insisted on keeping his sitters in position after he’d finished painting them but still needed to work on the background, citing “how their size and demeanor relate to you and the room.”

He did, however, accept stand-ins when necessary, borrowing Queen Elizabeth II’s tiara and having someone her size wear it so she could go on about her business after he’d finished her face, in 2001; and replacing model Jerry Hall with his studio assistant David Dawson after she found midway through a painting that she could no longer commit the necessary time. What made the pasty, flabby Dawson a particularly unlikely replacement for Hall – and Large Interior, Notting Hill (1998) one of the show’s most bizarre paintings – was that he had to pose as if breastfeeding a baby in the nude, as Hall had been doing in the background while an oblivious older man read a book in the foreground.

“I was disappointed at first that it didn’t work out with her, but in the end it didn’t really matter to the painting,” Freud said. “There was a certain quiet drama I thought about the original scene, and then with David as her replacement the drama got a bit louder.”

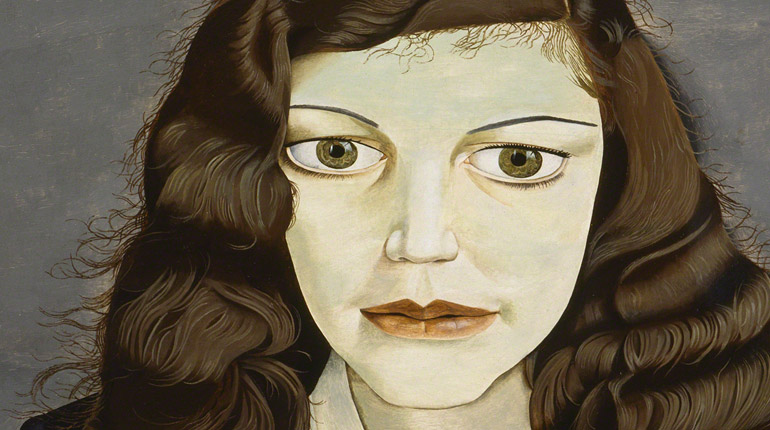

Early in his career, the drama – not to mention the remarkable level of detail in pictures like Girl in a Dark Jacket (1947) and Girl in Bed (1952), which seemingly capture every stray wisp of hair – arose largely from Freud’s extreme proximity to his subjects. He sat so close and stared so intently that he got headaches and eye strain; the claustrophobia is palpable but not the flesh.

That changed in the mid-1950s when, under the influence of his friend, painter Francis Bacon, Freud started trying to “(pack) a lot of things into one single brush stroke.” To that end, he switched to standing as he painted, constantly moving around to peer at his sitter from various angles, and abandoning his fine sable brushes for hog bristle. But while his brushwork loosened up, his process slowed as he mixed virtually every single brush stroke before applying it to the canvases. (The countless rags on which he wiped his brushes figure into paintings such as Standing by the Rags, 1988-89, in which a naked woman reclines awkwardly against a mountain of rags, for which Freud built an armature that’s hidden from view.)

As Freud increasingly realized his desire “to make the paint work as flesh does … to feel like flesh,” the drama in his paintings came as much from the way he rendered flesh and its myriad eccentricities as from his sometimes performative setups or the psychological dynamic between the painter and sitters ranging from wives and lovers to fellow artists such as David Hockney and the corpulent, charismatic performance artist Leigh Bowery.

“Layers of paint were built up almost like subcutaneous tissue, and the attentive, subtle energy that is reflected in Freud’s brush strokes is analogous to the pulsating liquidity of the breathing body that was in front of him,” Auping writes. “This certainly is part of the reason why we feel a living presence in Freud’s portraits, not just an image likeness.”

Indeed, although he described his work as both autobiographical and a group portrait in progress, Freud’s likenesses are rarely overly exact, and his pictures contain strikingly little biographical information about him or his sitters. Though he painted many of his lovers – in some cases decades his junior – and 10 of his 14 acknowledged children, they are often anonymous, identified simply as Woman Smiling or Woman With Eyes Closed. Nor are there any references to the fact that Sigmund Freud was his grandfather, though one of Lucian’s sitter-paramours told Vanity Fair the painter gleefully exclaimed, “What would my ancestor have made of this?” about one of her portraits. (She also said he preferred to paint her hung over.)

“When I become immersed in the process of painting someone, I can lose their relationship to me and just see them as beings, as animals,” Freud said.

That uncanny animal presence – not to mention the fact that a Freud survey of this scale is unlikely to be assembled again, and the Modern is the only U.S. venue – is what makes Freud’s portraits worth the willies – and worth the drive to get to them.

For a case of a different kind of willies, take in the Dallas Museum of Art’s recently acquired copy of Jerusalem-born, Berlin-based artist Omer Fast’s unnerving video 5000 Feet is the Best. It’s based on two conversations – one recorded, one not – Fast had with a Las Vegas-based Predator Drone aerial vehicle operator who was understandably more careful about what he said on camera than off.

The film alternates between a recurring scene between the Drone operator and an interviewer and three seemingly unrelated stories involving a man who impersonates a train operator, a grifter couple and a family on the run.

Chillingly, as the Drone operator discusses the technical aspects of his job – at 5,000 feet, he says, he can tell what kind of shoes a human target is wearing or whether he’s smoking a cigarette – his voice is laid over aerial shots of suburban landscapes, as if they were what the Drone operator was seeing. Shot with Hollywood-style production values while sewing an unsettling narrative confusion, 5000 Feet is the Best is as enigmatic as it is timely.

–DEVON BRITT-DARBY

Lucian Freud Portraits

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

July 1-October 28

Omer Fast: 5000 Feet is the Best

Dallas Museum of Art

June 23-September 30