Ten years ago, multidisciplinary artists and life partners Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin set out to trace a little-known bit of queer U.S history, an 1843 pleasure excursion by 100 men from St Louis to the Wind River Range of Wyoming, likely the first example of North American gay eco/party tourism. Vaughan and Margolin’s original art goal was limited at first, but along their own journey they realized this one project would become the first of a much larger artistic endeavor to discover lost LGBTQ histories and place those stories into some visual/conceptual frameworks. That quest became their 50 State project.

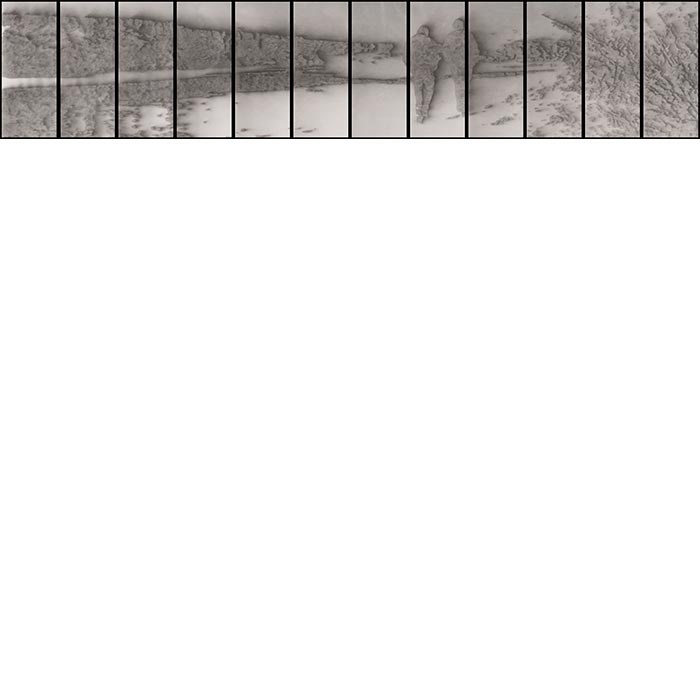

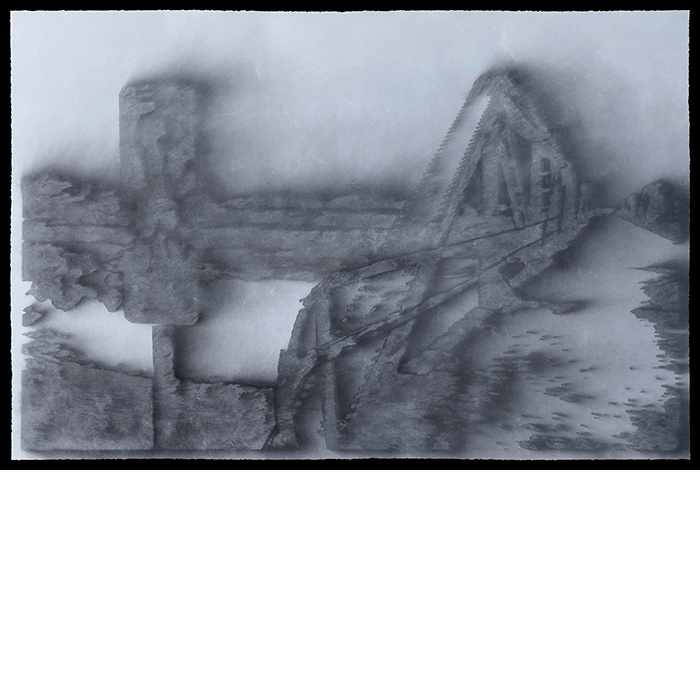

The intensive creation process for the Wayfinding wind drawings can take years. During their research period, they constantly photographed their journeys, spaces and finds along the way. To make just one wind print, they then go back through that photography or archival photos they unearthed, looking for those images that hold special narrative meaning to that particular state’s queer history: an old rail car, a decaying bridge, an oil rig on the Gulf of Mexico. From there the duo plan how to turn a particular photo into a stencil. The final art making process involves laying out the laser cut stencils, printmaking paper, and then using charcoal powder and an air compressor to blow the image into and out of existence.

The “drawing” that remains convey a kind of smoky outline or aura of history and stories lost in time, the ghostly imprint of lives lived and mostly forgotten, until these two artists explorers happened upon a lost novel, old newspaper clipping or whispered half-remembered story.

The inspiration for these wind drawings came to the duo when doing research for their Arkansas project as they looked for documentation of an interracial gay couple who lived in an opulent rail car in the Ozarks in the 1920s. The historical paper trail was “murky,” except for story and some hints in newspaper reports. They did have archival proof of the rail car itself, which had changed ownership over the decades before a fire destroyed it a decade ago.

They began to think about ash and charcoal as a possible medium.

“We started making these wind drawings where we were stenciling charcoal powder onto paper and then blowing it away and leaving that remnant of the blowing as the drawing,” says Margolin.

Yet before Arkansas, their Texas project had them wrestling with the “ephemeral quality” of people’s stories and history, as their research led them to a long forgotten 1895 dime store novel, Norma Trist, featuring a lesbian heroine.

For the Texas installation, they reprinted the entirety of the novel in loose stenciled graphite powder onto 16”x24” sheets, and then left the large-scale installation open to the environment. “Wind would go through and insects would go through and leave track,” describes Margolin.

Vaughan says ideas of impermanence and entropy have been elements in their work since they first started creating together, but with the wind drawings they believe they’ve found the medium to use as a thread tying the states together.

1 ⁄7

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin, The North Platte River, 2022, Charcoal powder and wind on paper, 62” x 312”

2 ⁄7

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin, The Split Image, 2022, Charcoal powder and wind on paper, 98” x 44”

3 ⁄7

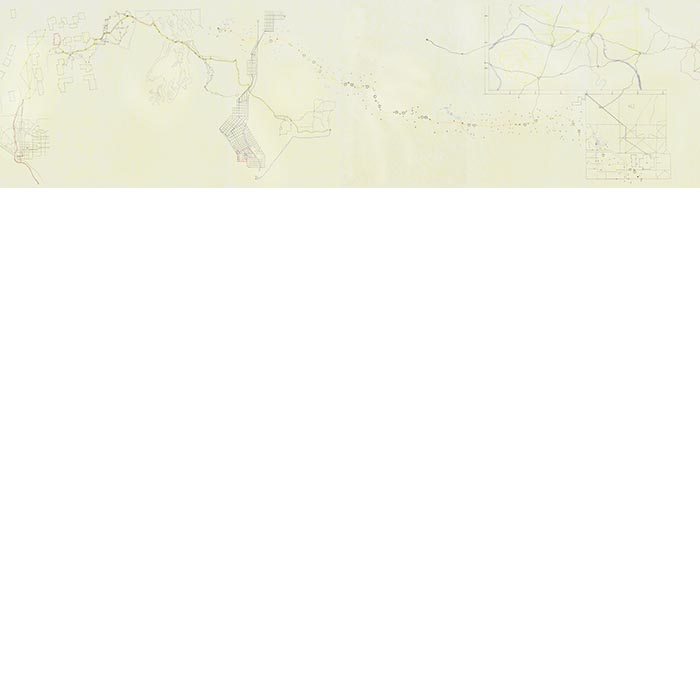

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin, Houston Migrations: Clint, 38°, 50’ 2, 2018, graphite, marker pencil colored pencil on paper, 17”x 56”

4 ⁄7

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin, Bridge Over the North Platte River, 2022, Charcoal powder and wind on paper, 43” x 64”

5 ⁄7

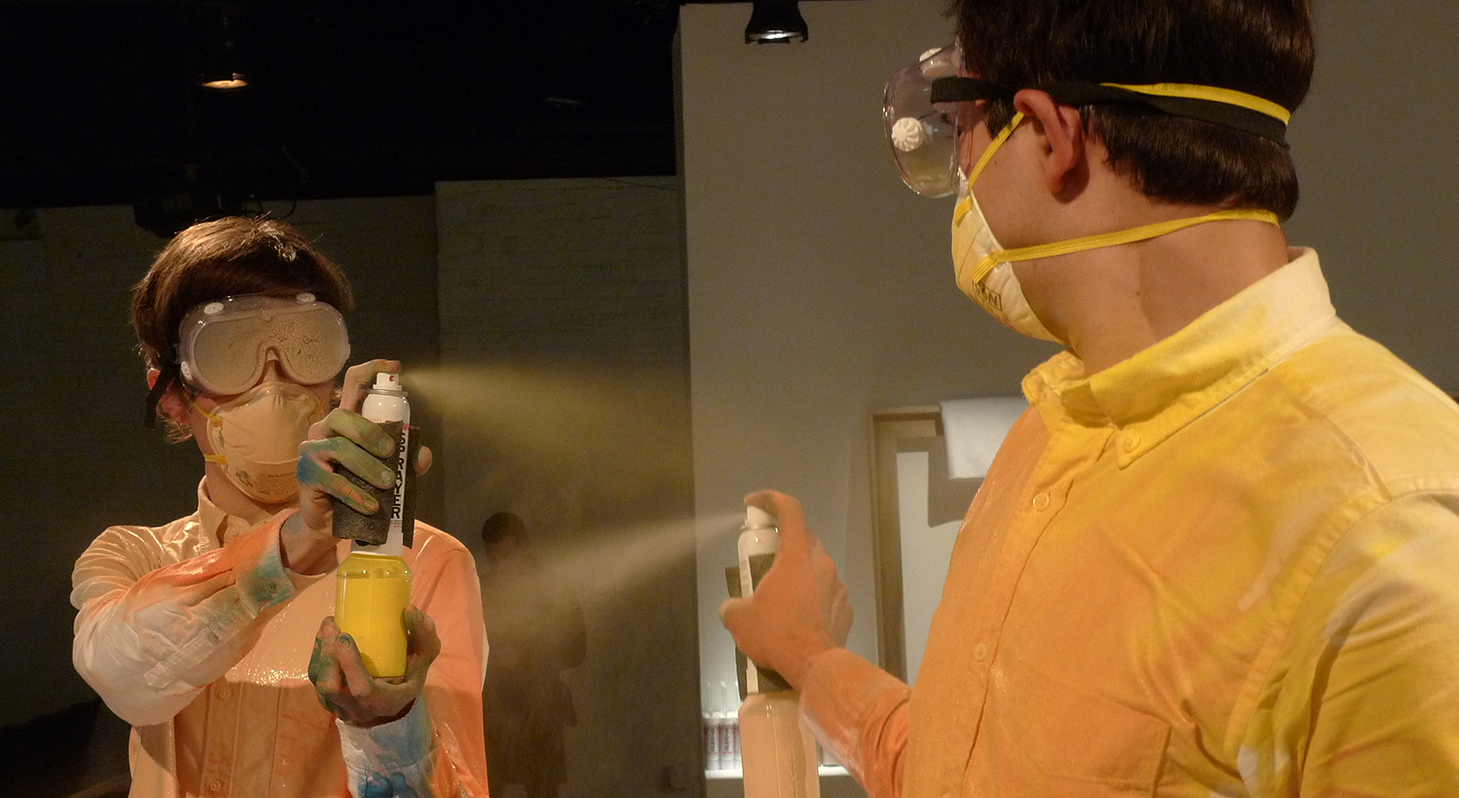

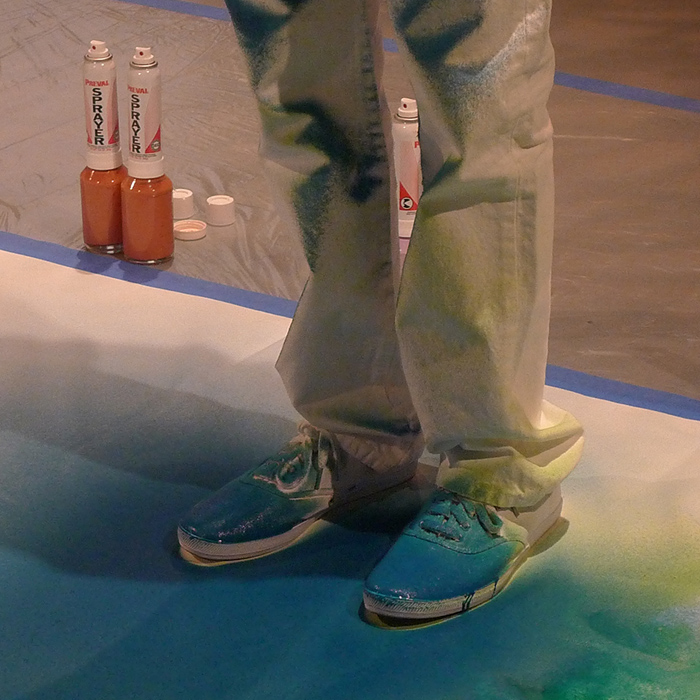

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin creating a Spray Piece. Photo by Janice Rubin.

6 ⁄7

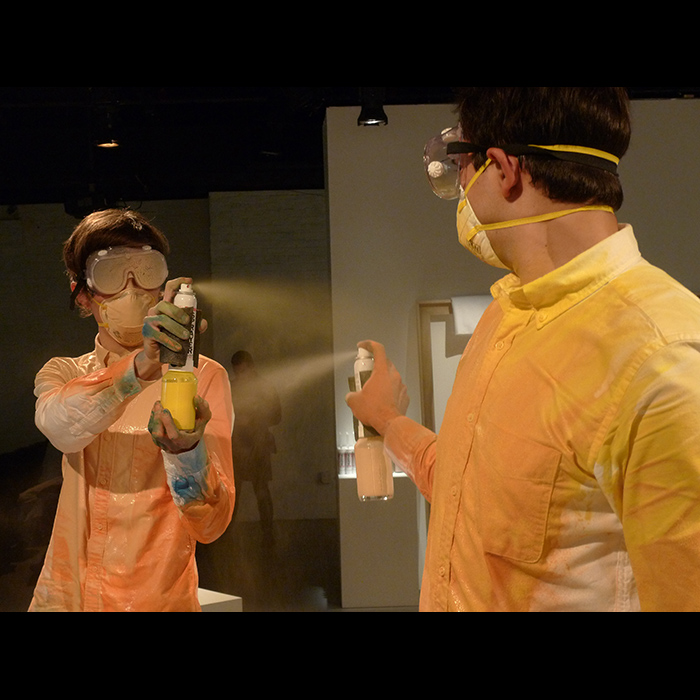

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin creating a Spray Piece. Photo by Janice Rubin.

7 ⁄7

Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin creating a Spray Piece. Photo by Janice Rubin.

The Blaffer exhibition will feature seven of the Arkansas pieces as well as new wind prints taken from images and photos from their Texas, Wyoming, Colorado and Louisiana projects. Only Oklahoma and its experimental documentary video installation will not have a representative piece, though the artists believe they will eventually find an image for Oklahoma, as well.

Separating the gallery in two will be two large-scale wind works created from images of their Wyoming project, one of wilderness still changed and marked as a pathway of the Oregon Trail and another a kind of self-portrait of Nick and Jake having a moment of art and life epiphany.

“This moment of us walking along this river was the moment that we both realized that what we wanted to be making was one of these for each 50 states,” says Margolin. “It was this feeling of being in the spectacular location in what we thought of as one of the most hostile states to people like us and realizing that we had some claim to the history of the place, that we thought we belonged in this landscape for the first time.”

Along with the wind prints, Wayfinding will feature a series of cartography portraits, depictions of queer community members as a map that chronicles their point of origin to settle in Houston. These “Houston Migrations” pieces will include two self-portraits of their own journey to calling the city home.

Vaughan believes offering a cloud painting performance holds a special meaning as part of the Wayfinding exhibition as these paintings work as the inverse of the wind drawings.

“With the wind drawings, we’re taking these images, whether we’re photographing them or using archival images, and erasing them through this process; and this is almost the reverse, taking these remembered palettes and imprinting on each other, creating a remnant drawing from that. So, it’s still a remnant process but it’s additive instead of subtractive. It felt they were potentially in a discussion with the Wind Drawings.”

—TARRA GAINES