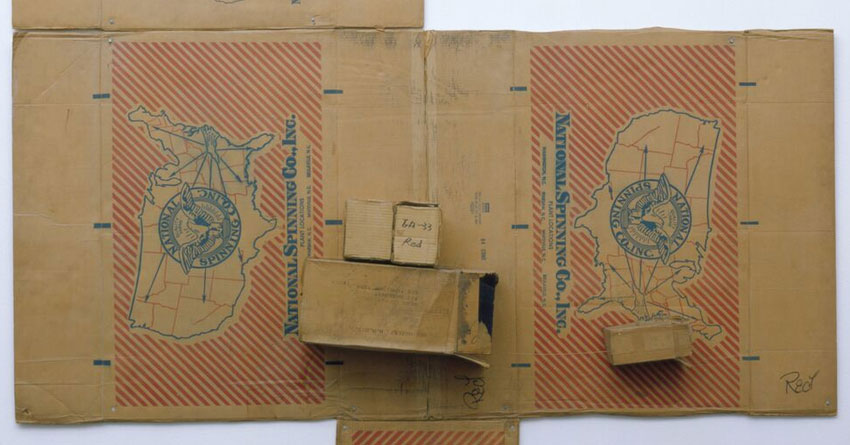

Robert Rauschenberg, National Spinning / Red / Spring (Cardboard), 1971.

Cardboard, wood, string, and steel, 100 x 98 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. (254 x 250.2 x 21.6 cm).

The Menil Collection, Houston, Purchase, with funds contributed by The Brown Foundation, Inc., and the following Menil Board of Trustees:

Louisa StudeSarofim, Frances R. Dittmer, Estate of James Elkins, Jr., Windi Grimes, Agnes Gund, Janie C. Lee, Isabel S. Lummis, Roy Nolen,

Charles Wright, Michael Zilkha.

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Artwork used with the permission of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Photo by George Hixson.

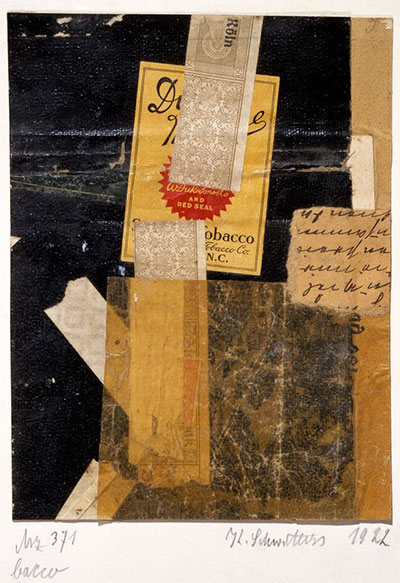

The Precarious is a small and quiet exhibition running at The Menil Collection through May 1, 2016. On the day I visited, a wall blocked the furthermost gallery in the west wing of the Menil—installation in progress—and, as a result, the entrance to the exhibition was easy to miss. The wall facing the entrance is anchored by a tiny Richard Tuttle sculpture, installed at ground level, and the large whiteness of the wall above and around it threatens to overwhelm the object. This threat—of dissolution, disappearance, destruction… of being overwhelmed—is at the heart of the exhibition, the first that David Breslin has curated at the Menil since his arrival from the Clark Art Institute last year. With objects made of cardboard, string, notebook pages, newsprint, and matboard, all stapled and glued together, hanging together by a string, the exhibition considers fragility as an historical, social, political, and aesthetic condition. “The very existence of the fragile artworks in The Precarious—not to mention the conditions that permit a future—hinges on the work and care of multiple others,” Breslin writes. And he cites theorist Judith Butler: “Precariousness implies living socially, that is, the fact that one’s life is always in some sense in the hands of the other.” It’s a poignant mention of the many kinds of labor that underpin the museum (and, of course, most of our lives): we live and work in a delicate balance, one that is predicated upon our relationships to others. How our humble creations survive (or don’t) is also contingent upon this balancing.

There are unexpected visual conversations here, between Kurt Schwitters and Danh Vo, Robert Rauschenberg and John Chamberlain, between Sari Dienes and Richard Tuttle. They are not necessarily obvious bedfellows, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t actually part of a larger conversation that sometimes gets lost in the creases of history. The exhibition threads together some of these social connections, giving space to how we live in conversation with one another. Sari Dienes’s Pink Hue (1950) is part of a longer series of rubbings she did, capturing the textures of natural and urban materials in subtle abstract compositions. In the 1950s, Dienes was showing at Betty Parsons Gallery in New York and attending D.T. Suzuki’s weekly lectures on Zen Buddhism at Columbia University. Many of the attendees of these lectures—including Jasper Johns, John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, Ray Johnson, Isamu Noguchi, and Morton Feldman—gathered at Dienes’s studio after the lectures. In 1959, Dienes would gift a salvaged stuffed bald eagle to Rauschenberg and he, in turn, would incorporate it into his combine Canyon, now at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Rauschenberg’s National Spinning / Red / Spring (Cardboard) (1971) is an anchor for The Precarious. Rauschenberg deconstructs the cardboard yarn box, turning it into a kind of vernacular icon. Seen together, Dienes and Rauschenberg’s works hint at the broader conversation between members of a specific community—conversations which must have swirled around issues of ephemerality, detritus, found objects, abstraction, and daily life.

![Richard Tuttle, II, 1-5 [third in an installation of 5 framed components], 1977. Paper and watercolor on paper, 14 × 11 in. (35.6 × 27.9 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston, Bequest of William F. Stern. © Richard Tuttle.](http://artsandculturetx.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/tuttle.jpg)

The Precarious includes several works by Danh Vo, pointing to a kind of intergenerational conversation: Vo’s fiat veritas, et pereat mundus (2013), a Budweiser box painted in gold leaf, is a direct descendant of Rauschenberg. Yet, Vo’s work is engaged with questions of historical memory and subjectivity, of labor and value. His ydob eht ni marw si ti (2015) consists of a quite-bodily marble sculpture in a wooden box on which the words: “Keep in a cool dry place” are printed. A reversal of “it is warm in the body,” Vo’s title makes an observation about preservation and its antithetical relationship to the heat of life. To keep this thing cold and safe is to undermine its sex, its dynamism. What does it mean to store objects in dark, cold rooms, to preserve a collection? Why do we insist upon taking care of such fragile objects? What do we value?

In large part because of its quietness, this sensitive collection of collages makes a significant gesture. It’s an ambitious exhibition, precisely because it insists upon the importance of fragility, absence, and intimacy. It is about the precarious state we find ourselves in, as bodies, as members of communities, and as historical subjects. It is also about how we mediate this precariousness. As Breslin observes, many of the collages in the exhibition were made post-World War II, as artists were grappling with the repercussions of large-scale devastation and unprecedented loss. Dominique and John de Menil’s emphatic belief in art’s place within community and as a part of a socially engaged politics finds a humble friend in this exhibition. “[The Precarious] is a prayer of sorts; it asks for empathy in our acts of looking and being,” Breslin writes.

Another reviewer could make an observation about the contrast between this quiet gem and the splashy, spectacle-heavy exhibitions that can be found at other institutions; I’m not sure it’s worth the word count to do so. In the end, the contrast would only serve as a distraction from the beautiful proposition Breslin makes. The Precarious makes a case for thoughtfulness and kindness, slowness and quietness, for subtlety. We are not here for long. We owe it to ourselves and to those around us to acknowledge that precariousness, to face our days and our encounters with kindness and with quietness. Be pensive. Take good care. Everything—whether made of cardboard, flesh, or steel—is ephemeral.

—LAURA A. L. WELLEN