Drive-in movie theaters, for the majority of Americans, are a relic belonging to earlier generations. Yet the memory-making experience of gathering those closest to us in the car, sharing goodies from the candy shack and catching a double feature together has managed to stand the test of time. Drive-ins are even having a renaissance under the social distancing guidelines and restrictions of 2020.

Houston Ballet has been one of a handful of sponsoring partners for the festival in previous years but as COVID secured her role as the mother of reinvention, Hance became curious if working together with the ballet company on an outdoor event would be a good match.

As for the format, Hance knew what she did not want—a virtual festival presentation.

Knowing that Houston Ballet had been looking for ways to activate the lot next to the building, she partnered with the company to develop the plan for a contactless drive-in experience.

“I have always loved the idea of sounds coming from cars and working with an FM transmitter,” says Hance, who frequently explores alternative spaces and facilitates non-traditional encounters with dance in her own work.

Frame x Frame Film Fest 2020 offers approximately 50 curated selections falling under three categories of film. Short works by local, national and international filmmakers in the “You Are Here” category give a current snapshot of the screen dance genre. Meanwhile, films under the category “Looking In” document a behind-the-scenes perspective on dance and those “Looking Back” provide a nostalgic opportunity to view the iconic dance scenes in classic movies such as Singin’ in the Rain, 42nd Street, White Christmas and Royal Wedding on the big screen.

1 ⁄ 9

Houston Ballet Center for Dance

Photo by Nic Lehoux (2011)

Photo courtesy of Gensler and Houston Ballet.

2 ⁄ 9

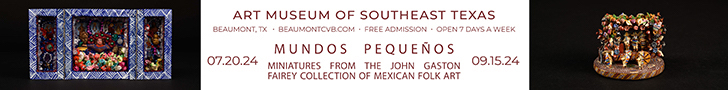

From Drawing.Dancing by Nicci Haynes

Photo courtesy of Frame x Frame Film Fest.

3⁄ 9

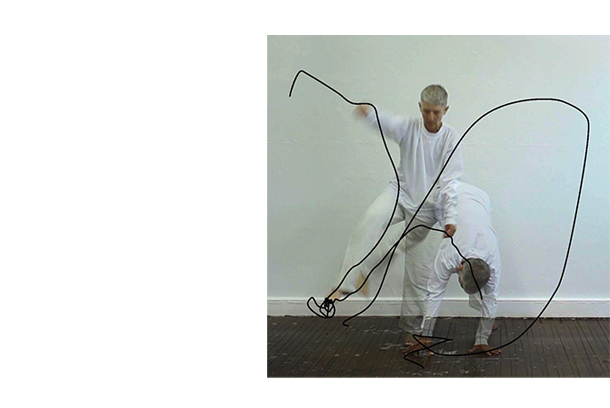

From The Call by Trey McIntyre

Photo courtesy of Trey McIntyre.

4 ⁄9

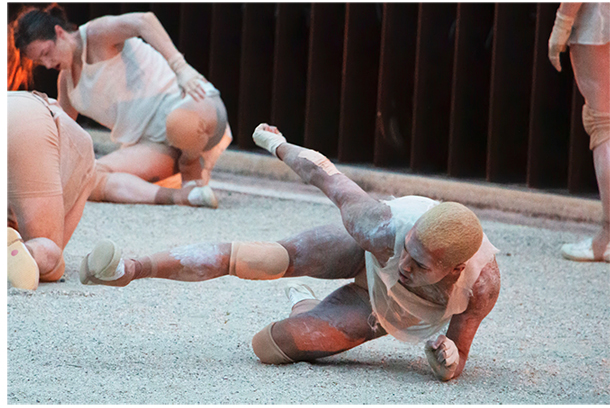

From ISOLA by Beatriz M Calleja

Photo courtesy of Frame x Frame Film Fest.

5 ⁄ 9

From If…a memoir by Sue Schreoder

Photo courtesy of Frame x Frame Film Fest.

6 ⁄ 9

From Liminality by Jennifer Akalina Petuch & Annali Rose.

Photo courtesy of Frame x Frame Film Fest.

7 ⁄ 9

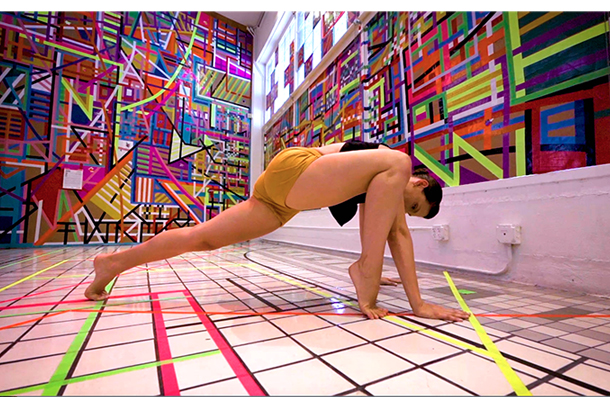

From Front to Back and Side to Side by Lydia Hance and David Rivera Dancer: Jacquelyne Boe

Photo courtesy of Frame Dance Productions.

8 ⁄ 9

From People in Cities by Rosie Trump

Photo courtesy of Frame x Frame Film Fest.

9 ⁄ 9

From Paper by Xiong Jiang

Performers : Kuang zhihen/Wu dali/Ye youzhen

Photographer : Shangbai Jiang.

Though certainly the artistry of the niche could be more fully and deeply explored over multiple weekends, she also wanted to engage new audience members, showing that dance made for the screen is not always obscure but has existed for decades in these well-known and accessible works.

Hance has also curated a group of documentary-style films that broaden the very definition of dance and who dance is for as representative of the values held by Frame Dance as an organization. Trash Dance documents the creative and logistical process of Austin-based choreographer Allison Orr as she collaborates with two dozen city sanitation workers to choreograph an extraordinary live garbage truck performance. Hance, who is also a dance educator and parent, hopes the Emmy-nominated film PS Dance! about dance education in New York City’s public schools might allow us to envision a more extensive dance program in Houston’s own public and private schools. “Breath Made Visible” explores the transformative and healing power of dance as the foundational principle upon which the life and work of dance pioneer Anna Halprin is based.

Four programs of short dance films have been curated by Hance and a cohort of choreographers and screen dance aficionados that includes Rosie Trump, Rebecca Salzer and Joshua L. Peugh. The “Best of Screen Dance” films they’re showcasing have largely been selected from an open call for submissions to provide emerging artists and filmmakers an opportunity to present work.

With more films than usual among the submissions this year that include dancers dancing in their living rooms, in the kitchen or elsewhere in their homes— what Hance calls “COVID dances”—the team has included what they feel are the most interesting and humorous to place among within the variety of screen dance works on the festival roster.

Dancemakers all over the world have been pushed into a space where, as Hance puts it, “artists are responding to the confines” right now. Choreographer and consummate reinventor Trey McIntyre’s Houston Ballet premiere of Pretty Things, as described on his website, was “shut down Covid-style on opening night” in March. In no hurry to return to New York, which had quickly become the epicenter of outbreak during the early months of the pandemic, McIntyre remained in Houston. During that time, he made three films, among them The Call, which is included in the festival line-up and features Houston Ballet company dancers Chandler Dalton, Connor Walsh and Chae Eun Yang.

As Hance wonders how storytelling and evaluating dance through a camera will impact live performance and choreography for those whose focus will inevitably return to momentarily-abandoned stages, she confirms her own desire to continue to use alternative venues as an opportunity for people to get and remain closer to a dancer. Even projected onto a giant canvas, it’s there she finds vulnerability, detail and nuance in the performance.

“I think we need to see dance larger-than-life,” says Hance, who believes the time-tested value of all that dance provides has never been more apparent than in a moment when we must look for ways to stay apart. “I think it’s going to feel hopeful.”

—NICHELLE SUZANNE