Jonathan Schipper’s Explosion at Fort Worth Contemporary Arts

What is the relationship between the art object and the passing of time? Can an object maintain it’s meaning as time goes by, and if it can’t, can the passing of time itself be the subject of an artist’s work?

Jonathan Schipper explores these dilemmas (and many more) in much of his work, illustrating the passing of time and its effects on objects by slowing time down, artificially recreating it and memorializing it, all while vehemently questioning the very primacy of the object itself.

Explosion is the Brooklyn-based artist’s latest work, created in conjunction with TCU and Fort Worth Contemporary Arts (FWCA), on view at FWCA through May 9.

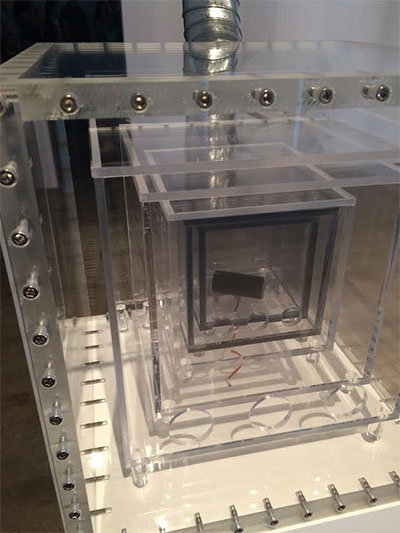

The show is in two parts. Exploding Box the installation piece is composed of seven lexan and plexiglass boxes (multiple boxes, one inside the other) enclosing pyrodex (a less sensitive form of black or gun powder) and an ignition wire, lined up side by side in FWCA’s front room. Over the course of the exhibition, the show’s namesake will take place in each box, at least we assume, at various times, leaving the outer layer of thick lexan intact but the plexiglass boxes inside the first, the shattered remnants of an explosion.

Exploding Box the video is the second piece, a digital video of an explosion taking place inside a tightly, center-framed box slowed down to a ridiculous number of frames per second, allowing viewers to see what they can’t in real-time.

It’s not much to look at, although some will (and have) disagree(d), and once the result of the explosions is taken down, the only art piece remaining will be the digital video, which I can’t imagine doing much for viewers out of the installation’s context.

But that’s kind of the point.

A certain skepticism of the art market, which is to be expected from someone of Schipper’s generation, is implicit in much of his work. He relies on experiments and temporary installations which often don’t generate an “art object,” in the traditional sense. In much of his work, Schipper seems to be attempting to illustrate the fallacy inherent in the idea that an artist (or anyone) could ever truly project meaning onto an object and expect his/her meaning to maintain its primacy through the passing of time. Permanence is false and the omniscient, omnipotent artist is a myth. In Explosion, as in much of Schipper’s work, things are constantly changing and the end result, in this case the state of the boxes post-explosion, can certainly be predicted, but can’t truly be known. Once the piece’s trajectory is set in motion its status as an object and inevitably its meaning, are out of the artist’s control.

It’s an interesting concept to grapple with and one that, like most artistic dilemmas, doesn’t actually have an answer. If the art object is a myth, it would follow our whole conception of at what point in the artistic process an object becomes art, would also come into question. Explosion the exhibition will change over the course of its run and viewers at various times will see different things, depending on how many boxes (which are scheduled to explode at pre-determined times throughout the show’s duration, unfortunately spontaneity was not an option) have been exploded on any given day. At what point, then, is it art?

It’s not an entirely novel concept, we’ve collectively been questioning the art object for quite some time, but Explosion, with its emphasis on creating equity between creation and destruction in the art-making process, refuses its audience the intellectual security of an answer.

Schipper does offer hints, albeit abstruse ones, as to where he stands on the subject thanks to a proclivity for documentation, which would seem to imply the entire history of an object as central to its understanding. Documentation is also central in elucidating his considerations of time. By artificially simulating actions, like he did in The Slow Inevitable Death of American Muscle, which featured two American muscle cars in an excruciatingly slow, ever-impending crash, helped by two very powerful rail lines and motors, Schipper creates powerful meditations on creation, destruction, time and the inevitability of its passing. By filming the happenings, Schipper can not only preserve the semblance of an art object, but he can manipulate our experience of time, as in the digital video of Exploding Box, allowing us the opportunity to truly consider it.

That video, essentially the end result of all of this painstaking creation and destruction, makes a strong case for the idea that the passing of time and its effects are the true objects in Schipper’s work.

I’d be remiss to not mention FWCA’s Sara-Jayne Parsons and Devon Nowlin, whose choice to invite Schipper in the first place marks a great early win in Parsons’ tenure at FWCA. Explosion was the result of a great deal of collaboration between Parsons, Nowlin, Schipper and the greater TCU community who contributed much to the final result.

Viewers who have been following Schipper for some time will find Explosion to be a natural extension of his practice, albeit one slightly less enthralling than Slow Inevitable Death, or Detritus, in which he used a computer programmed “robot” to create mini, constantly deteriorating “salt-sculptures.”

Schipper may not be the only contemporary artist exploiting man’s tenuous relationship with time, creation and destruction, in his work, and he certainly asks much of his audience. But those who prefer art which provokes more questions than it answers without descending into tedious academicism, have, and will continue to find Schipper and his work, some of the more rewarding art being made today.