For many years, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth has been in possession of what senior curator of photographs John Rohrbach calls “extensive holdings” of historical photographs documenting Native American cultures, from the 1840s through the mid-20th century—“more than 6,000 photographs, all told.”

The answer is Speaking With Light: Contemporary Indigenous Photography, on display at the Amon Carter through Jan. 22, 2023. The exhibition highlights the dynamic ways in which Indigenous artists have leveraged their lenses over the past three decades to reclaim representation and affirm their existence, perspectives, and trauma. The exhibition, organized by the Carter, is one of the first major museum surveys to explore this important transition, featuring works by more than 30 Indigenous artists. Through approximately 70 photographs, videos, three-dimensional works, and digital activations, the exhibition forges a mosaic investigation into identity, resistance, and belonging.

The exhibition begins with a prologue called “State to State,” which shows historical portraits of Indigenous people negotiating with presidents during the latter 19th century. It’s brought to the present with one of Wilson’s own “Talking TinTypes” of Enoch Kelly Haney, an American politician and internationally recognized Seminole/Muscogee artist from Oklahoma who served as principal chief of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma from 2005-2009, and previously served as a member of both houses of the Oklahoma Legislature. Haney passed away in April, but Wilson’s blending of historical photography process and modern technology means you can hear Haney speak simply by downloading a dedicated app.

“I’m acknowledging the trope of the ‘vanishing Indian,’ a notion that these people only existed in a bygone era,” says Wilson. “By playing with that and disrupting it with tech, I can bring this person to life and hopefully set the stage for the rest of the exhibition.”

1 ⁄10

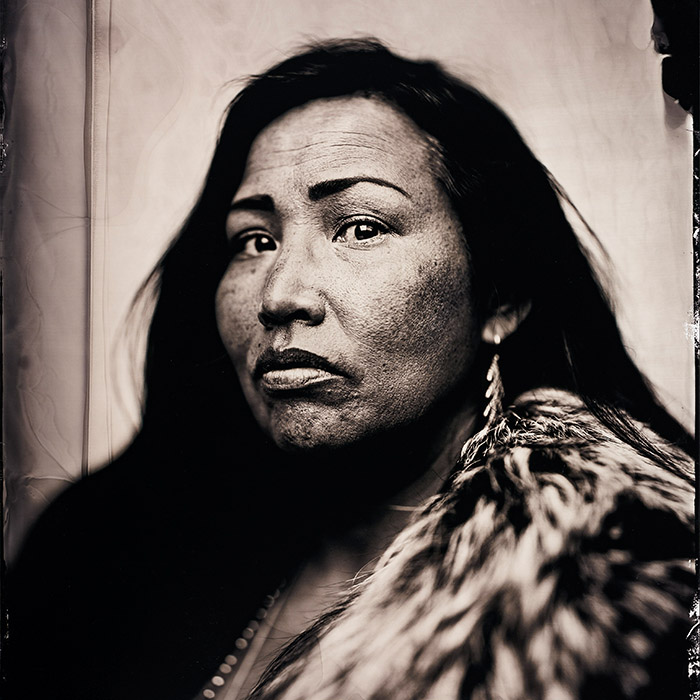

Kali Spitzer (Kaska Dena/Jewish) (b. 1987), Audrey Siegl, 2019, dye coupler with audio: Owl Song, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.58, © Kali Spitzer

2 ⁄10

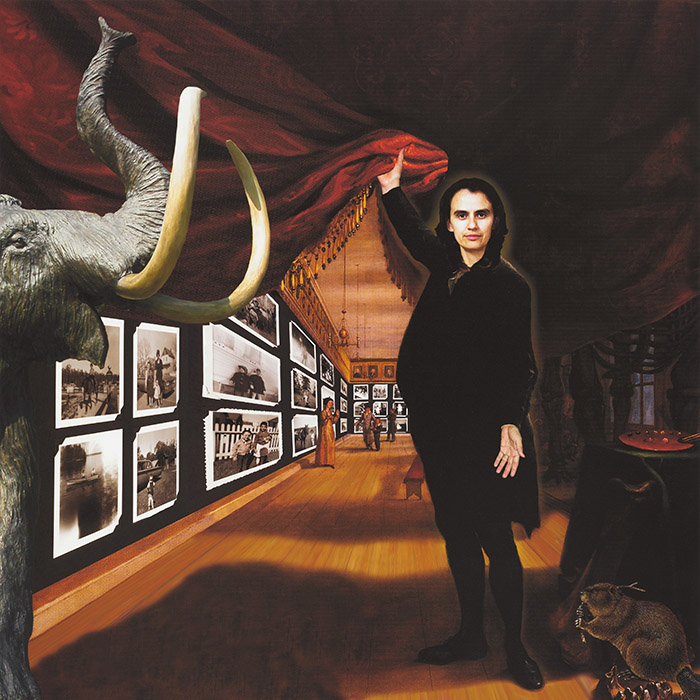

Rosalie Favell (Canadian, Métis-Cree/English/Scottish) (b. 1958), The Collector/The Artist in Her Museum, 2005, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.56, © Rosalie Favell

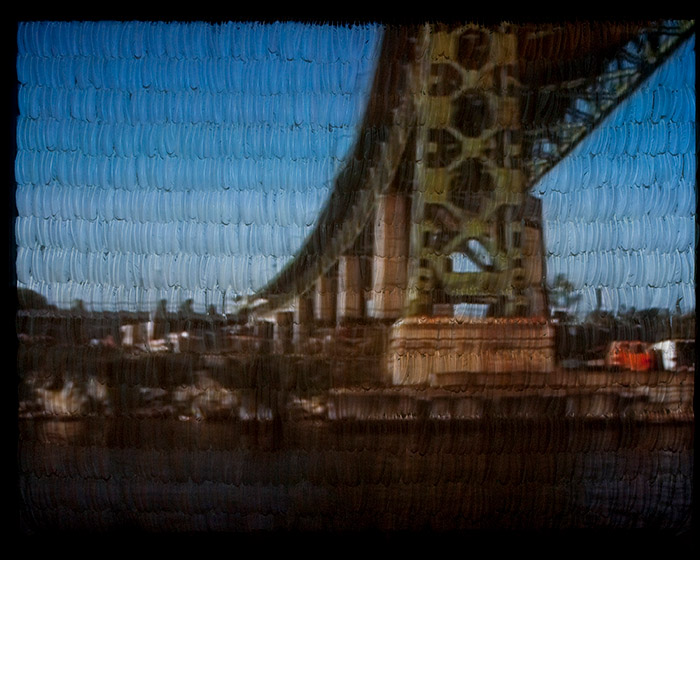

3 ⁄10

Alan Michelson (Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River) (b. 1953), Mespat, 2001, multi-media work, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (26/5774), © Alan Michelson

4 ⁄10

Cara Romero (Chemehuevi) (b. 1977), Evolvers (detail), 2019, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.55, © Cara Romero. All rights reserved.

5 ⁄10

Jeremy Dennis (Shinnecock) (b. 1990), Nothing Happened Here #10, 2016, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.9, © Jeremy Dennis

6 ⁄10

Zig Jackson (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara) (b. 1957), Indian Man on the Bus, Mission District, San Francisco, California, 1994, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.7, © Zig Jackson Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, North Dakota

7 ⁄10

Meryl McMaster (Canadian with nêhiyaw, British and Dutch ancestry) (b. 1988), Bring me to this place, 2017, inkjet print, Courtesy of the artist, © Meryl McMaster

8 ⁄10

Kiliii Yüyan (Nanai/Hèzhé and Chinese-American) (b. 1979), Joy Mask, IK, 2018, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.41, © Kiliii Yüyan

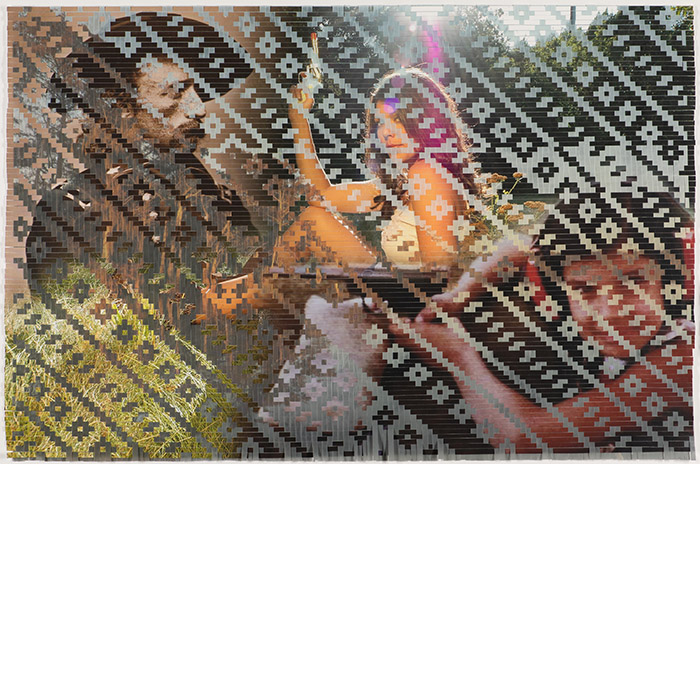

9 ⁄10

Sarah Sense (Choctaw/Chitimacha) (b. 1980), Cowgirl, Custer, and Young Impressions, 2018, woven archival inkjet prints on bamboo and rice paper, wax, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2021.8, © Sarah Sense

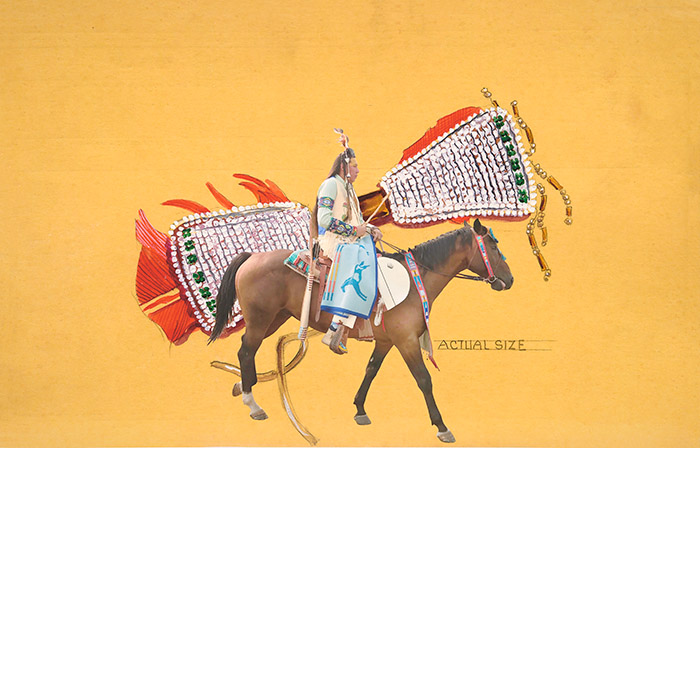

10 ⁄10

Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke) (b. 1981), Catalogue Number 1941.30.1, 2019, inkjet print, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, P2020.166.5, © Wendy Red Star

The next section, “Nation,” is about connection to community and the responsibility that brings. “This part asks, ‘what is home?’ What are the challenges of our communities, from isolation to demonstrations to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women?” says Rohrbach. “None of the works are suggesting they have answers, but they instead are trying to poignantly cope with these issues.”

The final part is named “Indigenous Visualities,” as a nod to the many different nations that are represented instead of one singular voice. This section, Rohrbach notes, is not directed to the Euro-American audience but instead within the Native American community, encouraging conversations about connection to the land and embracing myth and legend. It ends with a link to www.indigenousphotograph.com to show that Indigenous people are exploring their viewpoint all over the world, and not just in the United States or North America.

Wilson indicates that this exhibition will tour following its dates in Fort Worth, and hopes that it will grow to be an important resource for future scholars and other photographers—and the general public, as well.

“Wherever you are in the United States, you’re on Indigenous land,” Wilson says. “These perspectives, in particular, should be known and privileged—we were here first and continue to be here.”

—LINDSEY WILSON