A majestic ivory-billed woodpecker takes flight, the striking patterns of its black-and-white plumage flash across the still waters of a cypress swamp. The deep glow of twilight hues spreads across sky and water. Silhouettes of bald cypress trees, laden with Spanish moss, stand in silent witness of the elusive “Lord God Bird.”

“We are without a doubt in the middle of a widespread period of extinction of wildlife, and birds in particular,” Hassell laments. For an artist whose works have always been about nature, this awareness has sharpened his focus on conservation and preservation. “I’ve always loved nature and been inspired by it, but realizing it isn’t going to be around if we don’t pay attention, I’m really on more of a mission.” A somber tone accompanies some of his most exuberant images of wildlife, celebrating the animals that surround us while reminding us of the possibility of losing such beautiful creatures if we are not concerned about preserving their habitats.

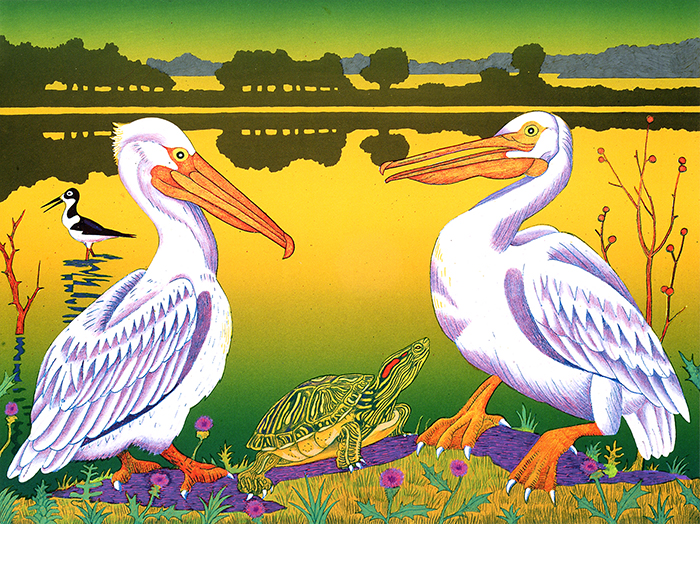

Egrets and pelicans, bobcat and wild turkey, dolphins and gar, migrating geese and monarch butterflies–creatures great and small from the East Texas and Gulf Coast regions will populate Hassell’s canvases and color lithographs at the Art Museum of Southeast Texas (AMSET) in Beaumont when the museum presents Billy Hassell: Topography (March 26-June 19). The title is an overarching reference that connects the map, the landscape, and the ecosystem. Beyond the contours of the landscape, Hassell is interested in depicting the entire ecosystem–the flora and fauna, colorful inhabitants of this wondrous world.

Known for his vibrant colors, Hassell has deliberately reduced the color palette in his latest paintings. In Shorebirds Following Schools of Fish (2021) and Cedar Waxwings Moving (2021), the background of water and sky is in brooding shades of gray. The birds, in their true colors, tread or fly through the flat, abstract seascape, onward with their daily occupations. “I’ve done very colorful works for years, but I decided to take color out of the work,” explains Hassell. It was a graphic, formal solution for conveying his idea. “I wanted to show that a world without wildlife or without birds would be a world without color. It is these occupants of the earth who illuminate it and give it the color it has.”

One might notice Hassell has a particular obsession with birds. Only two paintings in the entire show, Bobcat, Caddo Lake (2018) and Saltwater Life (2019), do not contain a feathered creature of some kind. Despite his fascination with birds, Hassell admits he is not the greatest birdwatcher. “I don’t go out and try to identify every bird I see. I don’t have a life list like a lot of birders have. It’s a very child-like interest. As a child, I was just in awe that they could fly. It never ceases to amaze me to see those formations of Canadian geese moving across the sky. I still try to wrap my head around where these birds go to breed, where they summer, where they winter.”

Hassell has painted birds for over 40 years now. “In a way they have become for me a symbol of all animals and all wildlife,” Hassell reflects. “They represent the nexus of all inhabitants of the world we live in, the world we share.”

1 ⁄6

Shorebirds Following Schools of Fish, 2021. 60" x 72", oil on canvas.

2 ⁄6

Whooping Cranes Over Salt Marshes, 2021. 50" x 48", oil on canvas.

3⁄ 6

Powderhorn Lake, Gulf Coast of Texas, 2015. 50" x 48", oil on canvas.

4 ⁄6

White Pelicans, 2006. 18" x 24", color lithography.

5 ⁄6

Roseate Spoonbills at Sunset, 2021. 50" x 48", oil on canvas.

6 ⁄6

Ghost of Caddo Lake, Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, 2018. 60"x72", oil on canvas.

The Gulf Coast region is no stranger to ecological tragedy. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill of 2010 inspired two color lithographs in the exhibit. For months the spill remained uncapped, making it one of the largest environmental disasters in American history. Hassell happened to be flying over the Gulf of Mexico at the time. “The whole ocean just looked like oil, but at the same time there was this shine, and these rainbows and iridescent colors,” Hassell recalls. He tried to recreate that kind of iridescence, something he thought was both “beautiful and terrifying.”

The result was Brown Pelican, Turbulent Sea, Silver (2011) and Brown Pelican, Turbulent Sea, Blue (2011). The waves are appropriated from ukiyo-e artist Utagawa Hiroshige’s iconic waves. Metallic silver ink gives the lithograph a shimmery look. Thick black lines animate the abstract waves. A large brown pelican rises above the roiling sea, appearing golden against the silver background. By contrast, the blue sea version seems much less dramatic. Hassell used this pair of prints to help raise money for the restoration of the Gulf Coast after the oil spill.

Over the last 20 years, Hassell has forged partnerships with several conservation organizations, creating color lithography prints to benefit important environmental initiatives. Nine lithographs are on display. Two are from the Audubon Texas avian art series, including Great Egret with Four Blue Eggs (2003), the first of many prints Hassell produced in collaboration with master printmaker Peter Webb. It is a complex image full of details that beckon the viewer to look closely. Beyond the giant egret that fills the frame, the intense orange sky along the horizon dissolves into warm yellows below and layered blends of magenta, purple, and blue above.

Powderhorn Ranch (2016) celebrates the largest existing unspoiled coastal prairie left in Texas. Recently acquired by TPWD, the pristine land is destined to become a state park. An endangered Henslow’s Sparrow, a largely unsung species that builds nests on the ground, looks content amidst grassland flowers. A meadowlark sings her song, sharing the stage with a dozen other bird species.

Hassell takes a rare dive underneath the water in Blue Water Reef (2016). He has observed first hand almost all of the wildlife in his works but relied on a team of marine biologists working for TPWD for scientific information on the fish and coral in this composition. The artificial reef off the coast of Port O’Connor is part of TPWD’s Rigs-to-Reef program. Decommissioned petroleum platforms were repurposed as marine habitats for diverse species in the Gulf of Mexico. A large red snapper occupies the central space, while an endangered Ridley’s sea turtle, bottlenose dolphins, barracudas, sardines, and various schools of fish glide above and below. It feels immersive, as if one is inside an aquarium, watching all the creatures swim by.

Increasingly Hassell finds himself working in an imagined world. He remembers falling in love with the natural world as a little boy, growing up by a creek that fed into White Rock Lake in Dallas. “I spent many many years combing that creek and catching things. It really was my little piece of paradise to explore.” The creek is no longer there, lost to the development of a subdivision. “That was the most poignant experience, watching a piece of nature in my own little microcosm of the world disappear.”

Hassell’s works invite the viewer to observe, to really see the beauty and colors of the natural world, to reclaim that child-like wonder. He is capturing a feeling. The first time he visited a bald cypress swamp, Hassell saw a small yellow bird. The bird makes an appearance in Egret, Grassy Lake (2010). It was a prothonotary warbler. He remembers vividly how the vision struck him. “It was this incredibly brilliant yellow in this sea of green—dark greens, light greens, all the greens of the swamp. It just lit up like a lightbulb, this flash of color, like a cardinal on a snowy day.”

—SHERRY CHENG