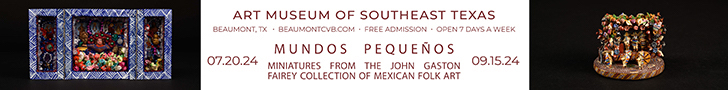

Dallas Museum of Art’s Senior Curator of Contemporary Art Katherine Brodbeck still remembers the textbook from her art history class as a college undergrad: Janson’s History of Art, a weighty, encyclopedic book that has been schlepped in countless backpacks across college campuses for decades. Originally published in 1962, the “survey of the major visual arts from the dawn of history to present day” has sold millions of copies over the past 60-plus years. Of those millions, the DMA likely owns the world’s only copy with a vulva-shaped hole carved into the center.

“Kaleta has done a clever repurposing of the textbook, so that there’s a woman on every page,” Brodbeck says with a grin, noting that the only presence of women within the book are mostly in nude paintings. “It makes you think about what women actually make art history.”

The DMA has been earnest and intentional in its efforts to acquire works by women and people of color over the past seven years and the current exhibition reflects that. Brodbeck began noticing comparisons between the works by women in the contemporary collection and some of the predominantly male artists they were referencing. “It kind of expanded from there,” she says, explaining the initial inspiration for He Said/She Said. “It does feature a lot of these recent acquisitions, many from emerging artists—but also some from pioneering feminist artists that just recently came into our collection.”

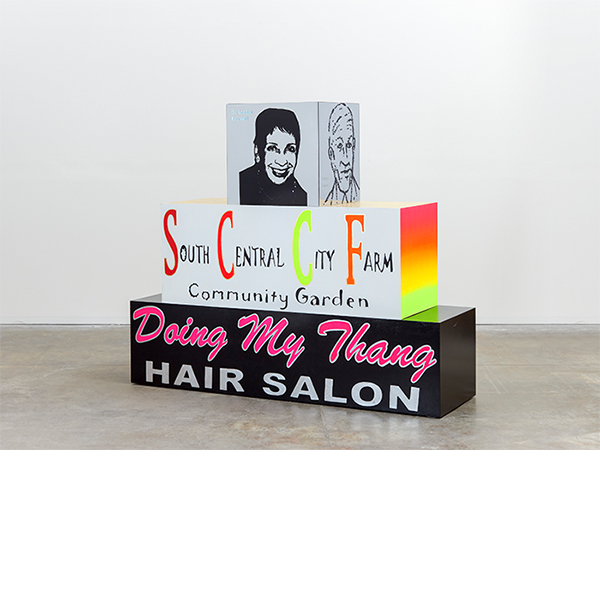

The Women and Appropriation section pairs playfulness with meatier subjects, such as the portrayal of women in mass media and as objects of sexual desire. Postmodernist works by women from the 1970s to 90s are represented here, including Pledge, Will, Vow, a thought-provoking video installation by American artist Barbara Kruger. In the center of the space is an installation by Sherrie Levine, an artist known for recreating masterwork paintings by male artists. After Man Ray (La Fortune):6 is Levine’s response to a 1938 work by surrealist American artist Man Ray.

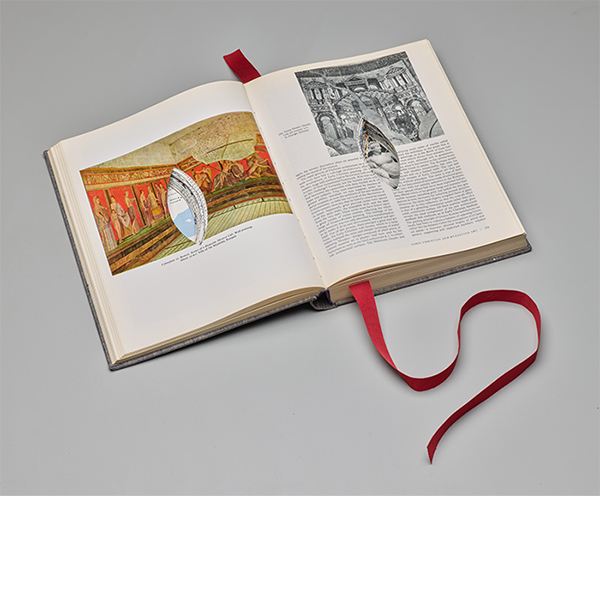

Black Female Subjectivity addresses the issue of underrepresentation of Black women artists and includes pieces by younger artists working today. “There’s a great juxtaposition between a work by Lauren Halsey, who’s a young artist from South Central Los Angeles, who did this stack of rectangular boxes that reference the signs you would see in South Central L.A.,” Brodbeck says. “And she’s referencing in part, Donald Judd, who is an American minimalist who made these rectangular boxes famous in the 60s and 70s in New York. She’s reappropriating that language, but also kind of broadening the story by showcasing how you can find it in the urban environment where she’s from in L.A.” The section also includes the DMA’s recently acquired photos by Lorraine Grady, an artist often celebrated for creating alternative spaces for women of color to share their art.

1 ⁄9

Kaleta A. Doolin, Improved Janson: A Woman on Every Page, altered text with red bookmark, Dallas Museum of Art, Lay Family Acquisition Fund, 2021.22. © Kaleta A. Doolin

2 ⁄9

Olivia Erlanger, Pergusa, 2019, silicone, polystyrene foam, MDF, plywood, and Maytag washing machine, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2019.63.A-B. © Olivia Erlanger. Courtesy of the artist

3 ⁄9

Lauren Halsey, South Central City Farm / Doing My Thang, 2022, acrylic, enamel, silver leaf, vinyl, and mirror on wood, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2023.2.A-C. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery. Photo: Allen Chen/SLH Studio

4 ⁄9

Sherrie Levine, After Man Ray (La Fortune): 6, 1990, mahogany, felt, and resin, Dallas Museum of Art, anonymous gift, 1999.108.A-H. © Dallas Museum of Art

5 ⁄9

Calida Rawles, In His Image, 2021, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Marcia and Jonathan Sobel, 2022.1. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

6 ⁄9

Barbara Kruger, Pledge, Will, Vow, 1988/2020 (still of Pledge), three-channel video installation, sound: 5:35 min. 35 sec., edition 3 of 4, +2 AP, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2023.18.A-C. Courtesy the artist, Sprüth Magers and the Dallas Museum of Art

7 ⁄9

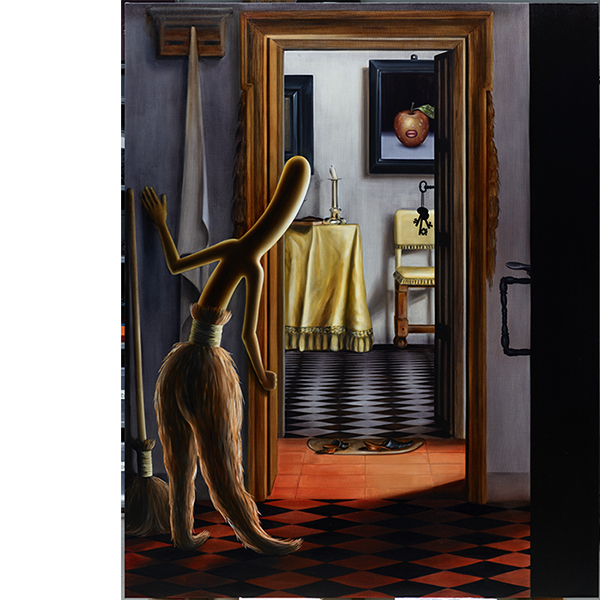

Emily Mae Smith, The Slippers, 2019, oil on linen, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the John Marquez Family Collection, 2020.37. © Emily Mae Smith

8 ⁄9

Ivy Haldeman, Bun Piece Dabs Forehead, Hand Lifts Rip, Thigh Left, 2020, acrylic on canvas, Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Andre Sakhai, 2021.16. Courtesy of the Artist and François Ghebaly Gallery

9 ⁄9

Julie Curtiss, Limule, 2021, acrylic and oil on canvas, The Rachofsky Collection. © The artist. Photo © Charles Benton. Courtesy White Cube

“The first idea is the siren in mythology or art history, where the woman is kind of this seductress,” Brodbeck explains. “Even the figure of the mermaid is really based on this kind of seductive, mythical creature who’s luring men and sailors from their safe ships to the rocky shores and ultimately to their death.” Brodbeck goes on to add that Erlanger’s concept of the piece was born while spending much of her time doing her laundry at laundromats in New York “and thinking about how this is really a space that’s both kind of gendered, as women are often sold appliances and told that they have to take care of the home.”

Friendships and Collaborations is the fourth and final section, ending the exhibition in an optimistic tone by recognizing the spirit of camaraderie between male and female artists. “Even though a lot of these artists are kind of necessarily critical of how exclusionary the canon has been towards women, they also do take great inspiration from the work of great male artists,” Brodbeck says.

Conversations centered on subjects of sexism, gender, and race can be complicated and even polarizing, which is why addressing them through art can often convey more on canvas than through words. Despite the gravity of the overarching theme of He Said/She Said, Brodbeck says she also wanted to bring a sense of levity to the experience. “I think there’s a lot of playful works in the show (so) that even if you’re not interested in issues of gender, I think that it’s really kind of eye-opening about the diversity of works—and especially the works by younger artists who are making you look at art in different ways. I’m hoping that people have a good time with it (and) that it’s not necessarily preachy, but that it works on both levels.”

—AMY BISHOP