Getting in touch with one’s heritage is something of an American pastime. This is borne out in the popularity of genealogical research sites and DNA analysis to discover one’s “roots.” But roots are tangled…and understanding our own lineage— where we fit in a tradition that began before us and (importantly) will continue after we are gone—is complex. Vicki Meek, Art League Houston’s 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, is using her upcoming exhibition to try to understand her own “artistic development over forty years.”

In Meek’s blog, art-racenotes.blogspot.com, she recounts how her mother was surveilled by the FBI until she turned the surveillance back on them. “She finally decided to fight back by snapping pictures of them which is the only reason they stopped hounding us whenever we went out,” the post reads. Although her activism takes a different form, Meek still considers these issues paramount. “My work is totally research-based,” she says. The things that “bug” her enough to make art about them revolve around a “spiritual lens of political [and] social issues around Blackness,” she says. “What I’m doing is exploring a bunch of topics and looking at them through the most humanizing element I can think of, which is the African cosmology.”

Audio of Meek singing links the Catlett-based works with those in the hallway, and speaks to another seminal moment in her life as an artist. “Becoming a mother changed my focus,” she says. And the final room in the space, the “front gallery, is a shrine to my own ancestors.” This space will incorporate “some of the elements in the vocabulary that I use over and over.”

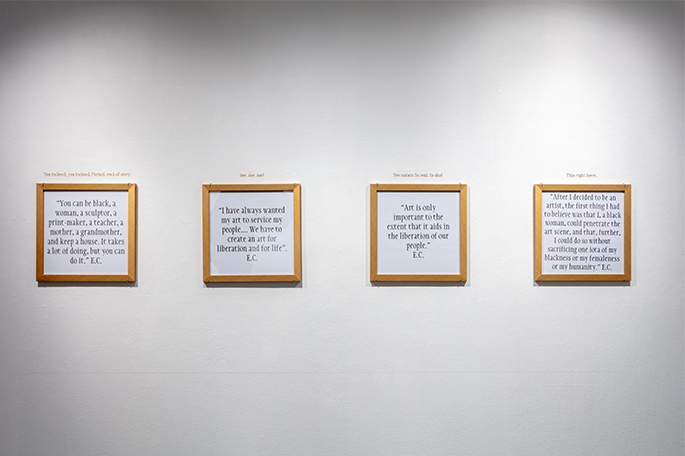

1 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston. Photo credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston

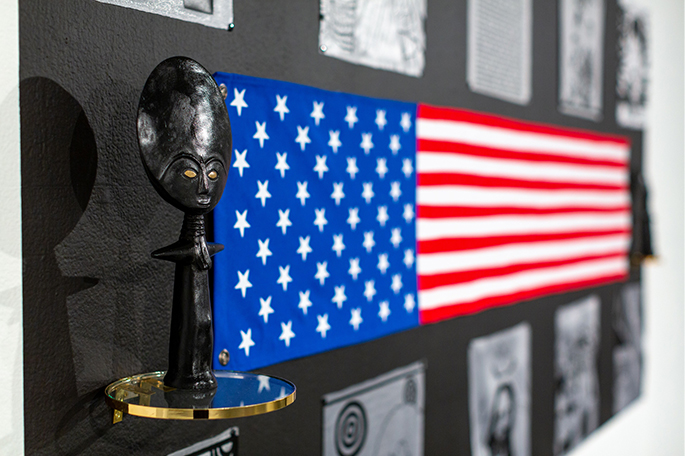

2 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation view from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

3 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

4 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

5 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation view from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

6 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation view from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

7 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

8 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

9 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

10 ⁄10

Vicki Meek, They paved the way: In homage to my ancestors, installation detail from The Journey to Me, site-specific installation, 2021 Texas Artist of the Year, Art League Houston, Photo Credit: Alex Barber and Art League Houston.

The pandemic has been a moment of reflection for the normally very busy artist, “I’m living my best life because I have time to be still,” she muses. For now, she’s in the first relationship of her career with a dealer—Dallas’ Talley Dunn Gallery— and she is working on a project with the Nasher on “how to memorialize erased communities of color.” The pandemic and the events of the past several years have been disheartening, but Meek is not one to give up easily. “America always seems to have to be pushed up against the wall,” she says, but “I tend to be an optimist. Young people change things.” In this way, The Journey to Me is an unusual exhibition for an artist being fêted with the moniker of Texas Artist of the Year. Meek takes an individual accomplishment and shows us how her own work draws strength from the past to seed the future.

—CASEY GREGORY