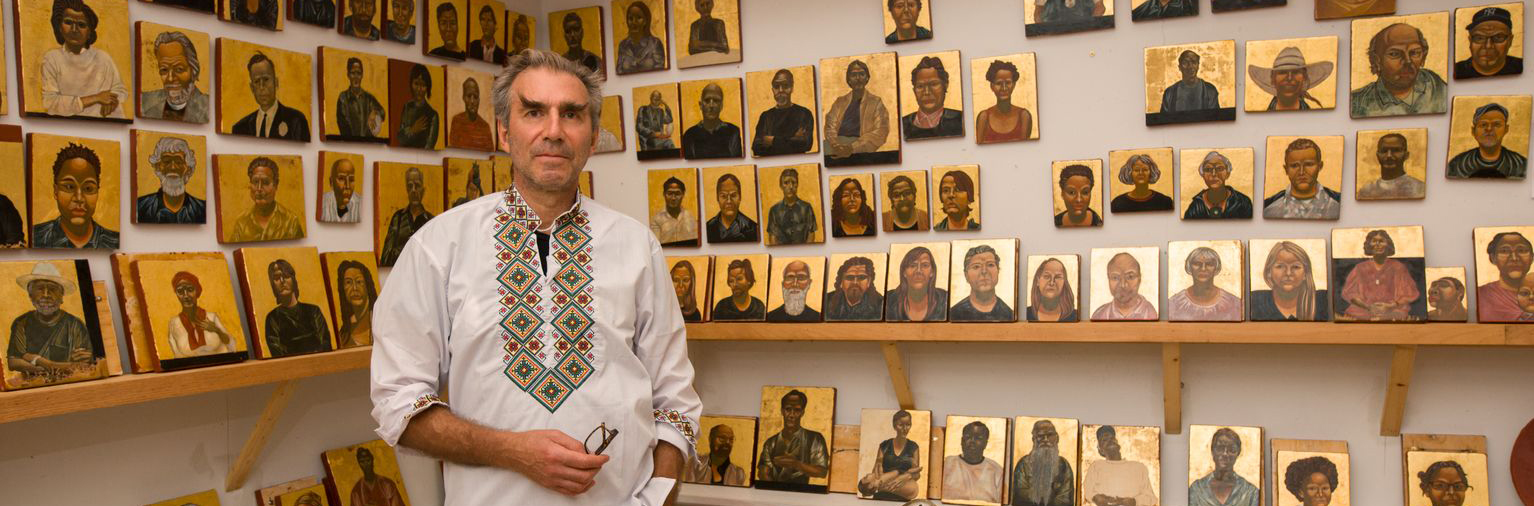

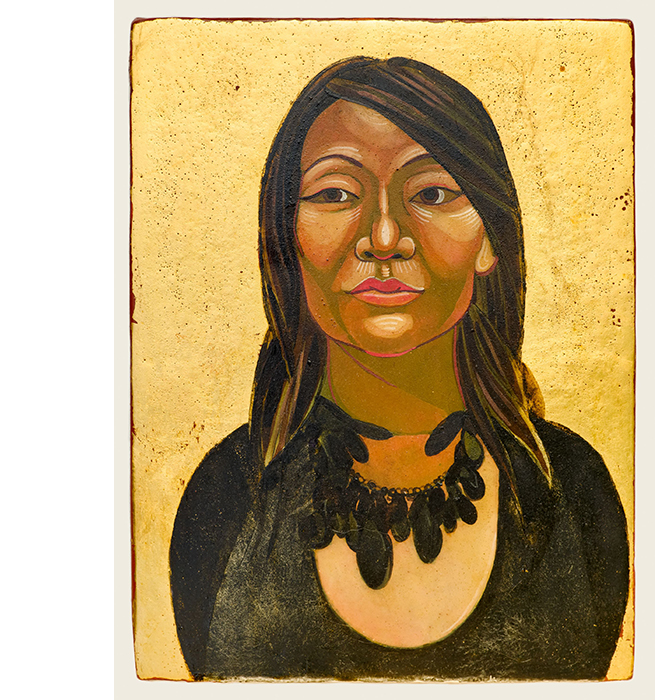

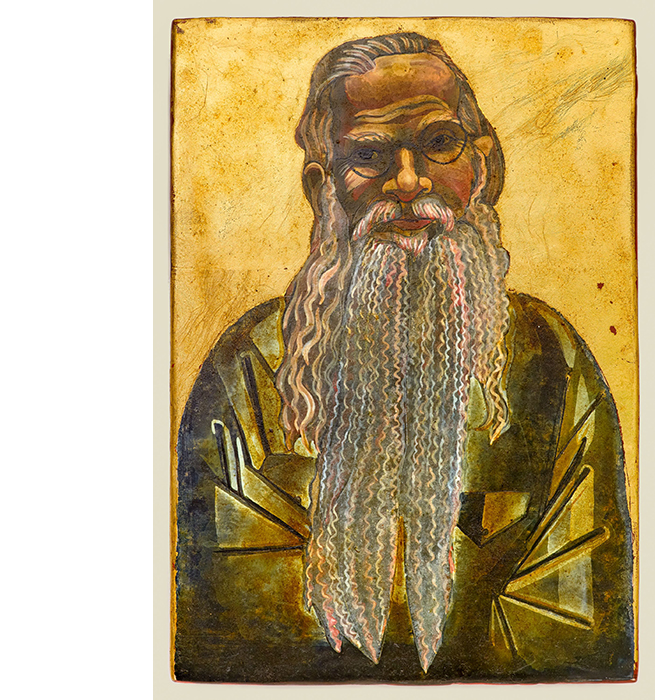

Nestor Topchy’s iconic portraits are about community and connection. Although they may resemble the traditional aesthetic of Byzantine-style icons, and the painting process is nearly identical, they are contemporary in both subject matter and intent.

The title was carefully chosen, as Topchy views his icons as “a growing strand of social and cultural DNA” that is open-ended. All the paintings in the show are dated 2008-2023, though many were completed prior to this year. He considers this series of portraits to be a single, ongoing work of art that represents and honors his community.

Topchy began the strand partially as a way to meet people when he was a stay-at-home father caring for his young daughter. Over the years, however, he invited many of his long-time friends and colleagues to sit for him as well. He sketches his sitters from life but also takes a photograph as a memory aid.

The process is actually called “icon writing,” and Topchy studied it at the Prosopon School of Iconology in New York City. His interest in icons dates back to his childhood when his Ukrainian father and Scandinavian mother took him to church services in a Ukrainian Eastern Orthodox Church in New Jersey. The initial impetus for this project was to honor the images he recalls seeing in the church.

Topchy takes pleasure in the labor-intensive, time-consuming process of creating the icons, illustrated by a display in the Menil library of the materials and methods he uses. The icons begin with a piece of wood, which the artist cuts and trims to approximately eight inches high by seven inches wide, although actual sizes vary. Using a stylus, he etches one of his sketches onto the surface. Next, he applies a base of red clay (iron oxide and animal-hide glue) and powdered marble. The portraits are then painted with a dozen layers of pigment mixed with an egg-yolk binder, but they may also include organic materials such as honey, beer, vodka, and cloves. A layer of gold leaf is applied, and the final step is adding the ozhivki, the lines that define the features and the hair. The portrait is then sealed with oil.

1 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Al “Kool B” LeBlanc), 2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

2 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Andrea and Lola Grover), 2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

3 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Arielle Masson), 2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

4 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Beth Secor and Sofonisba Anguissola), 2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

5 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Bora Kim),

2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

6 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy

Iconic Portrait Strand (Forrest Prince), 2008–23

Egg tempera and gold leaf on gesso over cloth on plywood

Courtesy of the artist

© Nestor Topchy

Photo: Caroline Philippone

7 ⁄7

Nestor Topchy, 2022 Photo: Caroline Philippone

“The portraits painted in the Byzantine tradition create a portal through which the divine is reached. To paint a mortal in the sea of gold light alone is to propose a saintliness that dwells within all people. To paint any man is to paint God’s face.”

In a short video of Topchy in his studio produced by the Menil, he says, “An icon is a window into heaven or the beyond or a place we can’t really access, so I’m starting with something I know—a painting, certain parameters that are defined and observable and moving toward something I’m trusting, something like hope, faith, and the process, but at the same time I’m having respect for the mystery of it. Mystery and the unknown aspects of it are very important as well. There is an inherent divinity in everyone.”

The iconic portrait strand is another aspect of creativity for this project-oriented painter, sculptor, installation, and performance artist. It weaves together his Ukrainian background, his spirituality, his love of process, and his desire to be part of a community. When Menil Senior Curator Michelle White sat for a Topchy portrait early on, the idea for the exhibition was born.

“The startling result not only elevates the subject but poses fascinating questions about the relevancy of the divine within contemporary art practices and what it means to capture likeness in a moment flooded with images.”

—DONNA TENNANT