In my first brief conversation with San Antonio-based artist Jose Villalobos regarding his 2018 Luminaria artwork, La Carga de Tradición, the artist was incorporating dance-based performance with wearable sculpture. At the time, one of his most recognizable works was a series of leather botas sliced along their decorative seams and taking flight with the help of clear hanging wire. A subtle undercurrent of violence was subsumed by the work’s beauty. Only a year later, at Austin’s Blanton Museum of Art, Villalobos performed Lengua, which featured the artist attaching a cow’s tongue to his own with string and dragging it across the scrawled initials of people whose gender and sexual identity resulted in their eventual murder at the U.S. border. The performance culminated in Villalobos slicing the appendage into pieces—an action that mirrored the violent excision of the voices of these Latinx individuals from the world. “I will say that my work has gotten more somber,” Villalobos confirms. Beauty is ever-present in his iconography, but the ante has been raised to the level of the sublime.

Villalobos seeks to scrape away some of the whitewash atop multiple, intersecting histories. Like whitewash, layers over generations accumulate to similar effect. “My grandfather was a bracero. They were only given a short-handled hoe.” he says. “I was raised in both cities,” Juarez and El Paso, equally.

The othering within the queer community and without is why Villalobos has turned to depictions of pain as a universal method of communication. In A Las Escondidas, the artist is dragged behind a horse into a rodeo pen, and then dons and removes various pairs of high heeled shoes as he lifts and stacks 50lb bales of hay. He struggles and sweats, literally slicing off the various pairs of high heels before graffiti-ing the hay bales with queer slurs. He concludes by stuffing the hay, scarecrow-like, into his fringed shirt, carrying with him both the exhaustion from the performance and the extra weight of gender and sexual oppression.

Villalobos relates a story about a woman who told him that she just couldn’t connect to his work because the queer experience was not familiar to her. “We all know what it is to be pinched,” he says. “Physicality is a process I use because we all have endured something. When people see that physicality, there starts to be a connection. The pain in the work is not just physical pain. Trauma comes in different forms.”

1 ⁄8

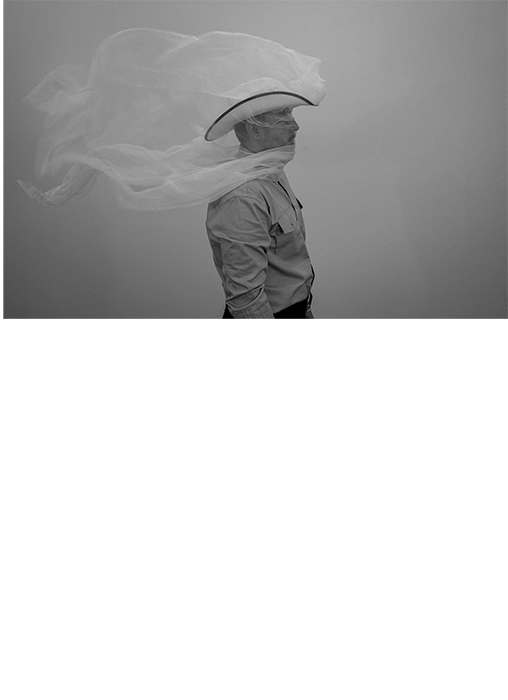

Jose Villalobos, Steer Straight, 2022. Photograph on glass, 15x20

2 ⁄8

Jose Villalobos, Con Todas Mis Chivas, 2021. Antique Suitcases, Horse pack, horse bit, pride flag, Dimensions variable

3 ⁄8

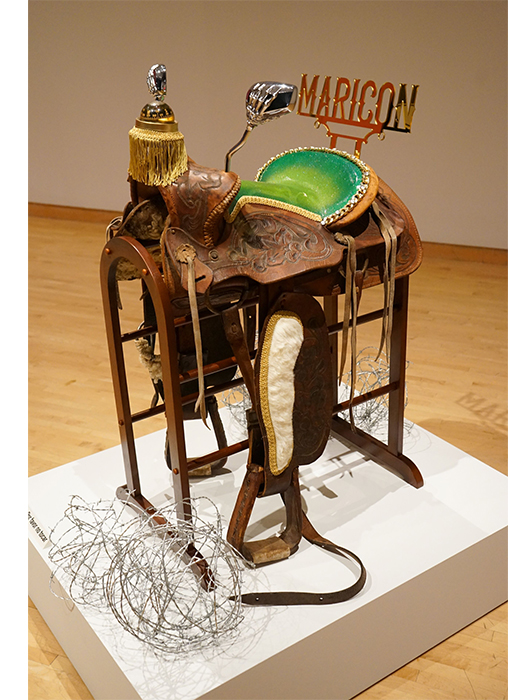

Jose Villalobos, QueeRider: Maricon, 2022. Bondo, fiberglass, car paint, chain steering wheel, saddle, Dimensions variable

4 ⁄8

Jose Villalobos, Lengua, 2022. Photograph on glass, 28x21

5 ⁄8

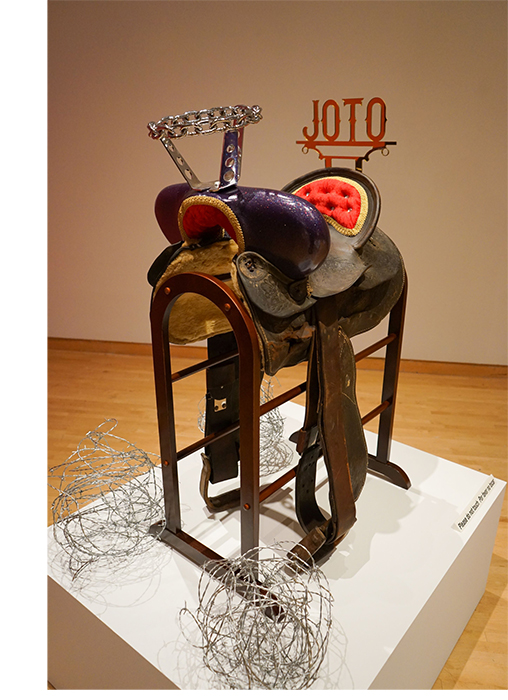

Jose Villalobos, QueeRider: Joto, 2022. Bondo, fiberglass, car paint, chain steering wheel, saddle, Dimensions variable.

6 ⁄8

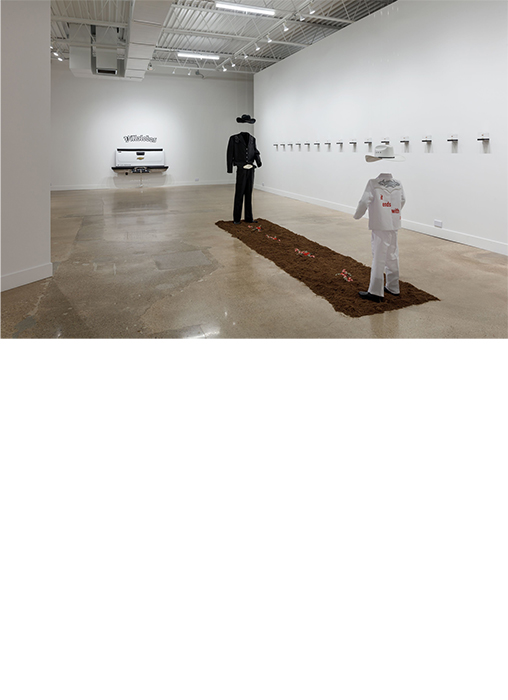

Jose Villalobos, Semillas, 2022 Installation, Dimensions Variable

7 ⁄8

Jose Villalobos, Lo Que Existe Entre Paredes, 2022 Dimensions Variable. Cinder blocks, paint, broken mexican coca cola bottles

8 ⁄8

Jose Villalobos, Deslizado, 2023. Dimensions Variable. Photographic Still of Video

While Villalobos is tapping into universal feelings of discomfort and attraction, what makes his work stand out is its specificity. From vaquero style shirts and boots to the sleek, industrial, custom-truck inspired sculptures in his 2022 Flight! Gallery show Trokiando, Villalobos demonstrates his intimate familiarity with the signifiers of a certain brand of machismo. We are all invited to participate, but the work sings in a harmony all its own.

—CASEY GREGORY