The park in El Paso covers 372 acres running right up to the Rio Grande, and it gives many visitors a big surprise.

López Ramírez, a dancer and dancemaker, is on a mission: awakening the El Paso community to the wonders of Rio Bosque Wetlands Park. Here, and the Wind: an Exhibition about Process, running March 23-May 26 at the university’s Stanlee & Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts, will give viewers an echo of a project she spearheaded last year.

As the leader of Rubin Center’s Community Engaged Practices in the Arts program, López Ramírez led a battalion of UTEP students and El Paso residents into the park to explore it and put their creativity to work. Their work climaxed in a performance in the park last November, part of a multiyear project called “Experiencing the Bosque.”

That changed in the late 1930s, when a federal project redirected the river into a canal meant to control its flow. The bosque, robbed of water, withered. But an effort launched in the 1990s aimed to rejuvenate part of the bosque using treated wastewater, and the El Paso park began to turn green again.

“It’s a really special place,” says López Ramírez. Her love for the natural world took hold as she grew up in Colombia—at the same time as she took dance lessons and enjoyed dancing as a social experience. On occasions from birthday parties to street festivals, she recalls, dancing was “part of the glue that held the community together.”

That vision of dance’s social power stayed with López Ramírez after she came to the United States to study dance in college. After graduation, she says, she focused “my dance practice in ways that would engage the people around me. I started discovering the transformative power that performance and movement can have in communities.”

1 ⁄7

UTEP Alumn Simoné Velasquez performing as a Spirit during Experiencing the Bosque on November 5th, 2022. Image Credit: Rigo Alberto Zamarron.

2 ⁄7

UTEP music student Alexandria Campos showcasing the wearable art before performance. Image Credit: Jess Tolbert.

3 ⁄7

Community member Janeth Herrera performing in the Rotifer section of Experiencing the Bosque on November 5th, 2022. Image credit: Rigo Alberto Zamarron.

4 ⁄7

Community member Karin “Kay” Moore performing as the Mother Spirit on November 5th, 2022. Image credit: Rigo Alberto Zamarron.

5 ⁄7

Audience members move through UTEP dance students performing as Rio/Flow during Experiencing the Bosque on November 5th, 2022. Image credit: Rigo Alberto Zamarron.

6 ⁄7

UTEP dance student Ana Monroy performing as a Spirit during Experiencing the Bosque on November 5th, 2022. Image credit: Victoria Áviles.

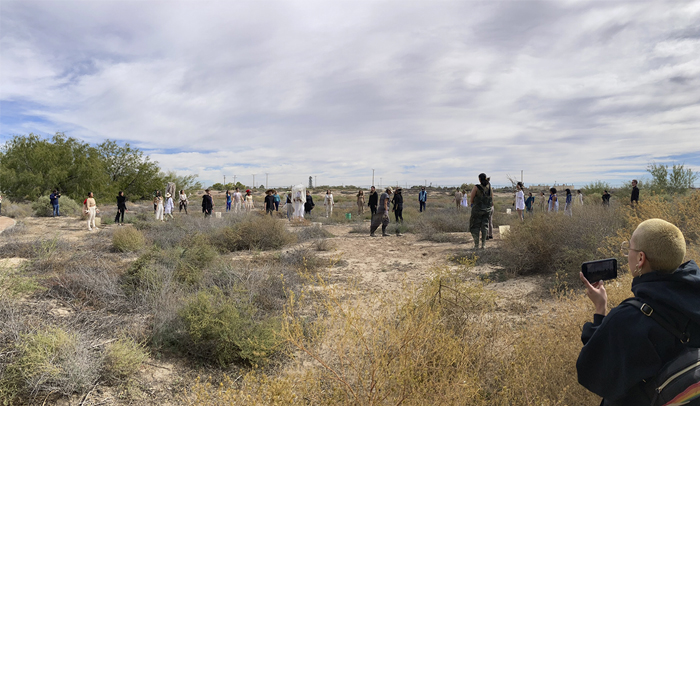

7 ⁄7

The entire cast gathers for the performance finale on November 5th, 2022. Image Credit: Rigo Alberto Zamarron.

The sessions that culminated in last fall’s performance were one incarnation of that. López Ramírez began by ushering the students and volunteers into the park, where she told them to close their eyes, listen to the sounds and feel the ground supporting them.

“We don’t have many chances to stand on the earth—on the ground—any more,” she says. “It informs our posture, our alignment, the placement of our muscles. The ground beneath us moves and breathes and has life. … Just (perceiving) that alone, for a lot of people, is a big stretch.”

López Ramírez, who bases her dancemaking on improvisation, then spurred her group to observe their surroundings and imagine movements in response. One participant focused on the birds populating the area.

“When most of us would pretend to be birds, we would flap our arms,” López Ramírez says. But she led the group beyond that. “The gesture of opening a wing—how does that feel if it’s in your scapula? Then take that gesture and work with it to open your back in a different way. … You start to work with this concept that originated from the observation in the natural landscape, and then use it to research your own body.”

Here, and the Wind will spotlight the entire process. A documentary film will let viewers relive the performance, but the show also will include video from the improvisation sessions, costumes, photos, texts and maps.

López Ramírez even is looking for ways to guide viewers in “an embodied, physical experience.” A card in the gallery might suggest that they walk in a particular direction, for instance, or notice what first catches their attention after they shut, then reopen, their eyes.

“I think of dancing in a very broad way,” she says. “Having intentional pathways in which they walk to different places—to me, that’s a dance.”

-STEVEN BROWN