Flesh Made Word in the Art of Robert Indiana

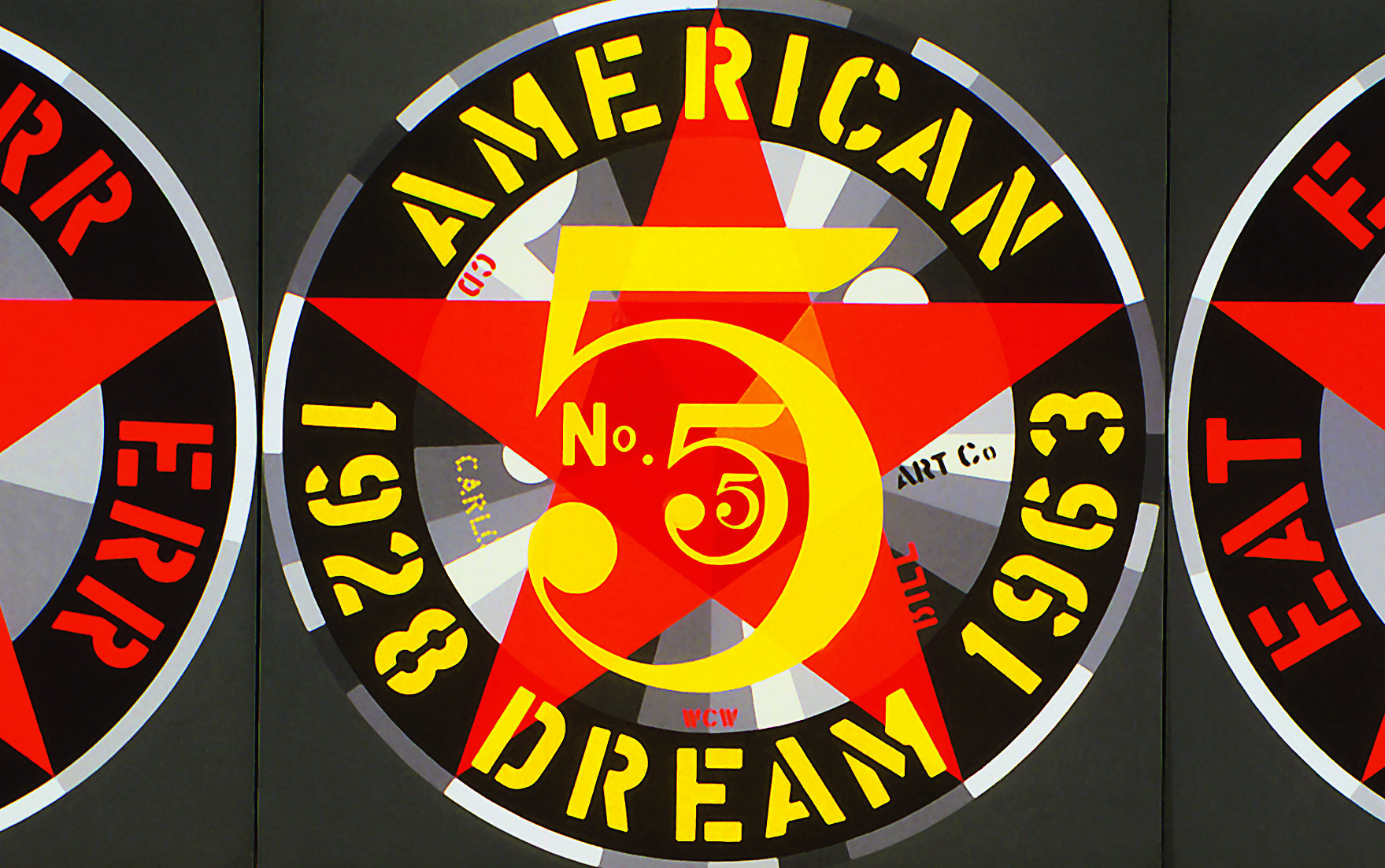

IMAGE: Robert Indiana, The Demuth American Dream #5 (detail), 1963. Oil on canvas. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Gift from the Women’s Committee Fund, 1964. ©2014 Art Gallery of Ontario; Morgan Art Foundation, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

After reading and publishing A+C contributor Scott Andrews’s insightful essay on the traveling exhibition, Robert Indiana: Beyond LOVE in our March issue, I had an inkling of how embarrassingly little I knew about Indiana’s work. But while I was prepared to be surprised by the experience of seeing the show a few weeks ago at San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum, I didn’t expect that it would haunt me as it has.

He is a master of scale, perhaps because of his totemic forays into sculpture.The relationship of your body to the paintings turns out to be critical, especially when he makes you turn your head as full-circle as you can manage while stepping left to right and back again to read their messages. Despite the relative dearth of overt figurative imagery in his oeuvre, the body takes on recurring thematic importance—not through depiction, but through language. Eat, Die and Hug are among his most frequently stenciled words, showing up in various permutations, along with the word Err—something we do with our bodies as well as our hearts and minds.

Indiana has referred to his early 1960s assemblages, made with salvaged wooden beams, as “phallic sentinels.” He acknowledges an allusion to the crucifixion, which he also attempted to depict, abstractly, in the late 1950s, when he was under the sway of Ellsworth Kelly, his lover at the time. After meeting by chance in 1956, the two artists got loft spaces near each other in Coenties Slip, a tiny strip near the East River in Manhattan, and spent time drawing each other as Indiana listened to Kelly—the older, already successful artist—hold forth. A shift soon appeared in Indiana’s work, which became hard-edged and abstract. While the abstraction gave way to text and symbols, the hard edge stayed.

“My painting life began with Ellsworth,” Indiana later said. “Before Coenties Slip, I was aesthetically at sea. With Ellsworth, my whole life perspective changed. All of a sudden I was in the 20th century.” Also: “I never thought about color until I knew Ellsworth.”

What to make of Indiana’s “Americasm”? Is it simply a misspelling of Americanism, a Freudian slip, or apt wordplay by someone with a knack for it?

Many years later, lovers are represented by their names, which work their way into his deeply moving homages of 1989-1994 to Marsden Hartley’s elegies to Karl von Freyburg, a young German cavalry officer and likely lover killed in the early months of World War I. (A McNay companion show, Robert Indiana’s Hartley Elegies, presents all 10 screenprints in the series; the Whitney survey includes a couple of the paintings.)

“For Indiana, the Hartley Elegies were not simply another homage to an artist whose innovative use of symbolic portraiture foretold his own, but a more forthright identification with a pictorial history of representing homosexual love and loss than had been possible in the early 1960s,” writes catalogue contributor Sasha Nicholas. “What was once veiled and ambiguous in Indiana’s work now surfaced amid the heated identity politics and AIDS crisis of the late 1980s—particularly with Indiana’s decision to unite the names of Hartley and von Freyburg in the center of several canvases and to refer to his own past and present relationships through adding names and initials such as ‘Ellsworth’ and ‘TvB,’ a Germanized allusion to his Vinalhaven friend and fellow artist Tad Beck.”

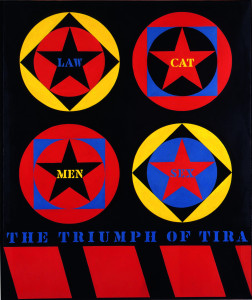

“Indiana’s use of seemingly commonplace and generally familiar words, names, dates, numbers, and symbols belies his work’s deep underlying content and masks the artist’s method of loading his art with hidden, coded messages,” Barilleaux writes. “As a result, Indiana’s approach to text became seminal to the work of artists who emerged in the wake of the Pop movement, and who themselves have become critical influences on artists who have emerged in the decades since.”

Indiana inverts the Gospel passage, “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.” Flesh is made word in the art of Indiana, who once said, “A first condition for the artist [is that] he must be apart.”

Robert Indiana: Beyond LOVE

McNay Art Museum

Through May 25

This column expands upon the ideas in a previous blog post.