Thanks to a gift from Chicago collector Madeleine Plonsker and her husband Harvey, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, now has the most complete collection of post-revolutionary Cuban photography anywhere—nearly 400 works by some 80 artists. For two years, MFAH photography curator Malcolm Daniel and MFAH research associate Raquel Carrera have been organizing Navigating the Waves: Contemporary Cuban Photography, which opens Sept. 29 and runs through Aug. 3, 2025.

The museum’s collection of Cuban photographs began in 1994, when FotoFest dedicated its festival to Latin American photography and included an exhibition of Cuban photographers. Fifteen photographers traveled to Houston, and MFAH photography curator Anne Wilkes Booth acquired 17 of their photographs. She continued acquiring Cuban photographs, and the collection grew to nearly 100 works.

Daniel’s research associate for the show, Cuban native and art historian Raquel Carrera, has been working with Madeleine in Cuba for nearly a decade and working with the museum curator for two years to organize the exhibition in Houston. “I can’t imagine doing the show without her,” Daniel said. “She has served as organizer and translator, both here and on my two trips to Cuba.”

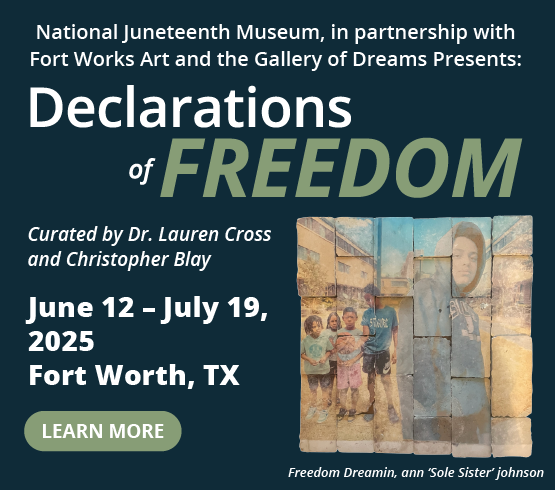

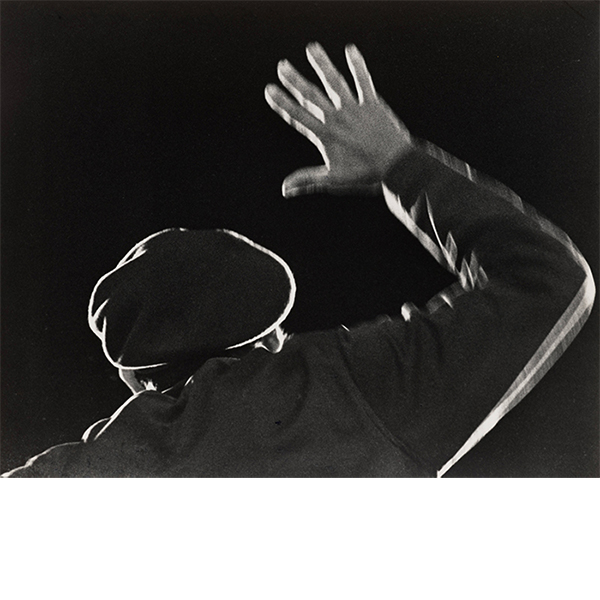

Navigating the Waves is organized into four categories, beginning with the so-called “Epic” generation of photographers, which includes Alberto Korda, Raúl Corrales, and Osvaldo Salas, all of whom were given access to Castro and his inner circle, the heroes of the revolution. The show opens with Korda’s iconic portrait of Che Guevara, Heroic Guerrilla, perhaps the most famous of all Cuban photographs. Taken in 1960, according to the curators, “it came to function like a secular image of a martyred saint” after he died while trying to organize a revolution in Bolivia in 1967. Five Points of Fidel, a dramatic view of Castro speaking, is by Salas, an established photographer in New York who returned to Cuba just two days after the revolution. These and other photographers from this period used their photographs to further the ideals of the revolution.

1 ⁄7

Osvaldo Salas, Five Points of Fidel (Cinco puntos de Fidel), 1982, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, gift of the estate of Esther Parada. © 1982 Osvaldo Salas

2 ⁄7

Alberto Korda, Heroic Guerrilla (Guerillero heroico), 1960, printed 1995, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by Dan and Mary Solomon. © Estate Alberto Korda

3⁄ 7

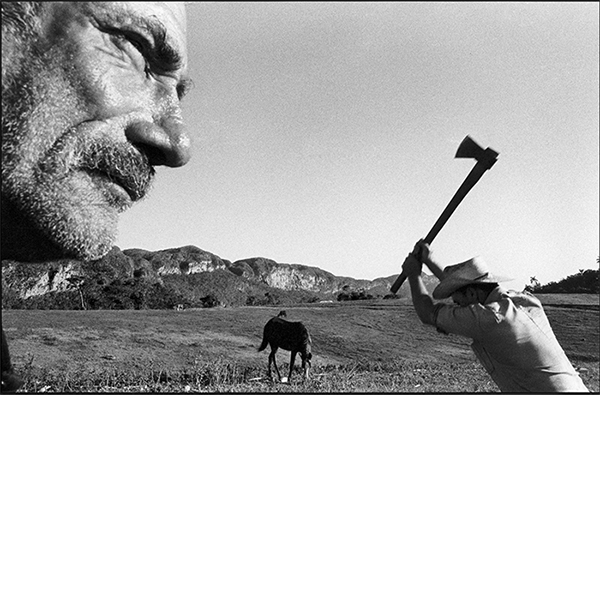

Eduardo Muñoz Ordoqui, from the series Zoo-Logos, 1992, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by Clinton T. Willour in honor of Mickey Marvins. © 1992 Eduardo Muñoz Oroqui

4 ⁄7

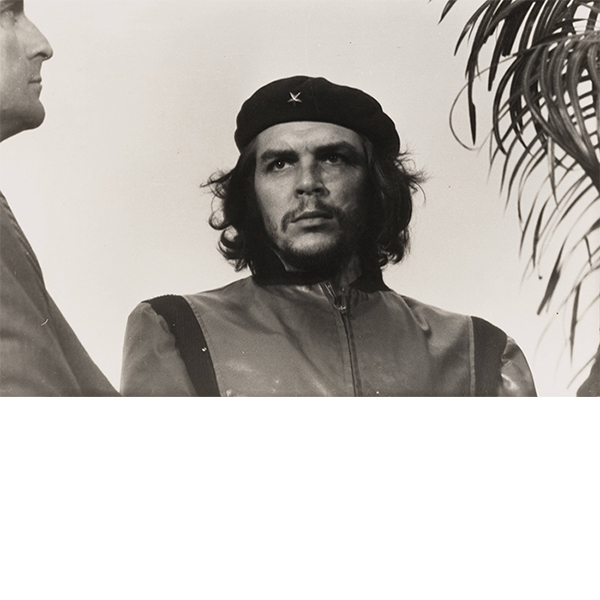

Raúl Cañibano, from the series Country Land (Tierra guajira), 2009, inkjet print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Madeleine P. Plonsker Collection, promised gift of Madeleine and Harvey Plonsker. © 2009 Raúl Cañibano

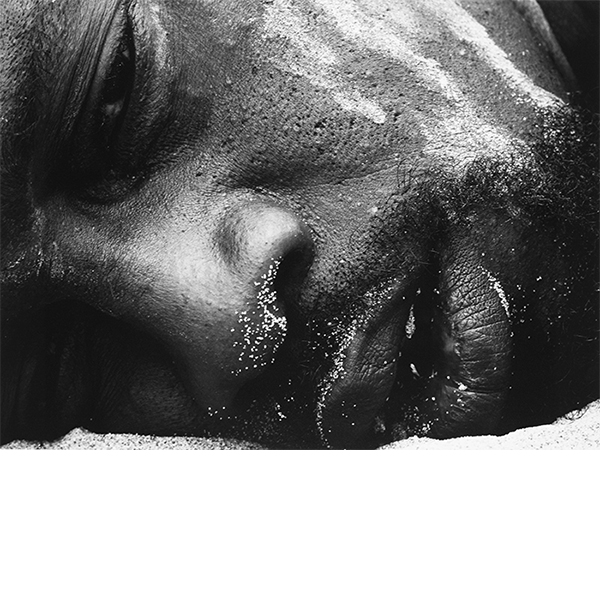

5 ⁄7

Jorge Luis Álvarez Pupo, Wandering Paths No. 15 (Caminos errantes No. 15), from the series Wandering Paths (Caminos errantes), 2009, gelatin silver print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Madeleine P. Plonsker Collection, promised gift of Madeleine and Harvey Plonsker. © 2009 Jorge Luis Álvarez Pupo

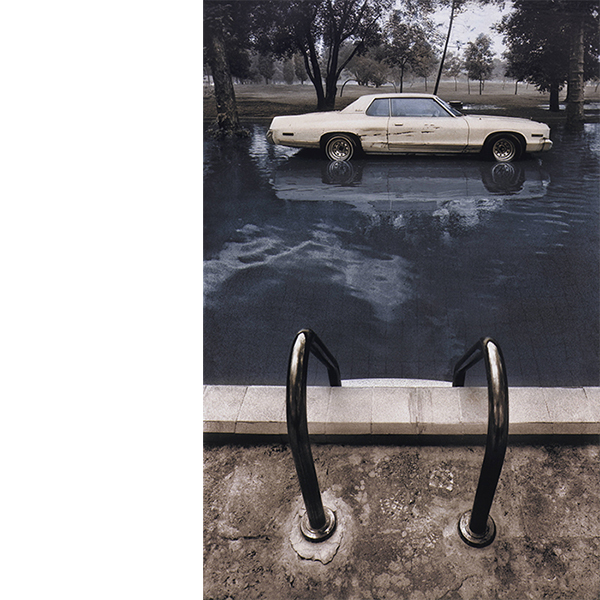

6 ⁄7

Gory (Rogelio López Marin), from the series It’s Only Water in the Teardrop of a Stranger (Es sólo agua en la lágrima de un extraño), 1986, printed 2023, chromogenic print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by the Photography Subcommittee, 2023. © 1986 Rogelio López Marín (Gory)

7 ⁄7

Adrián Fernández, Untitled No. 1 (Sin título No. 1), from the series Pending Memories (Memorias pendientes), 2017, printed 2020, inkjet print, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, museum purchase funded by Photo Forum 2021. © 2017 Adrián Fernández

In the 1980s, Cuba relied heavily on the Soviet Union for economic support, and when it collapsed at the end of 1991, the island experienced an economic and political crisis. The next gallery focuses on photographers who turned to more personal subjects, including gender roles and sexual identity. René Peña González’s moody portrait of a nude male wearing a long, beaded, silver necklace is a haunting image. Arien Chang Castán became interested in bodybuilders, and his photograph of two bulked-up prisoners working out is from his series Root Vegetable Diet. Many of the photographs in this section are black-and-white portraits of male nudes or young gay men.

The final gallery contains photographs made since 2005, some utilizing the same patriotic symbols as earlier work but with a subtle undercurrent of disapproval. Adrián Fernández, the son of two architects, shoots industrial remnants, unfinished construction sites, and public propaganda. Cuban and Soviet flags painted on the side of a building are weathered with age in Alfredo Sarabia Fajardo’s Tangle. A web of electrical wires and electrical boxes reference the aging power grid in Cuba, the result of an ongoing shortage of fossil fuels.

Navigating the Waves presents an opportunity to examine the history and ongoing development of photography in Cuba since the start of the revolution. For photography curator Malcomb Daniel, organizing the show was an illuminating experience. “I was not that familiar with Cuban photography,” he said. “Finding these artists was a discovery for me, and it’s been very exciting.”

—DONNA TENNANT