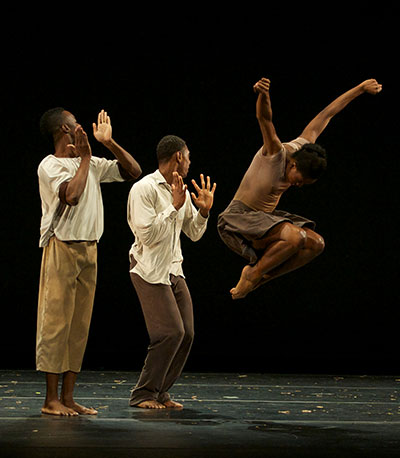

Dallas Black Dance Theater’s Tyrell V. Rolle in Talley Beatty’s Mourner’s Bench. Photo by Jaime Truman.

Dallas Black Dance Theatre Offers Historic Works

Photo by Jaime Truman.

While Dallas Black Dance Theatre performs work by historically significant African-American choreographers year-round, a special emphasis is placed on the pioneers and their progeny during the company’s annual Cultural Awareness concerts. This year’s shows, to be held Feb. 20-22 at the Wyly Theatre in the Dallas Arts District, spotlight a pair of exemplary male solos composed by black-dance giants Alvin Ailey and Talley Beatty in the middle of the 20th century. The program also features newer pieces in the African-American dance tradition by Troy Powell and Dianne McIntyre, and the premiere of a new work by company dancer/resident choreographer Richard A. Freeman Jr.

“Our children need to remember,” Dallas Black Dance artistic director April Berry says, of the struggles and triumphs often depicted in black-dance works. “The farther you get away from the history, the less the children of the culture know or are educated about those periods. We’re really creating a legacy and a historical conversation for those who were not a part of that era and did not experience those situations and times.”

Inspired by the triumph of jazz, Reflections in D is a three-and-a-half-minute solo that Ailey made in 1962 for himself as a breather between longer works. Yet despite its brevity, his interpretation of the introspective Duke Ellington piano piece of the same name contains just about everything you need to know about Ailey’s choreographic gifts. Sharply articulated upper body movement, especially elongation of the torso and arms, speaks to the purposeful clarity that distinguished his style. It will be danced by the versatile Sean J. Smith at the evening performances and by Freeman at the matinees.

When Berry arrived at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1980 to start her 11-year career with the company, Dudley Williams had taken over the role from Ailey. “There’s a lot of port de bras in that solo, and I couldn’t take my eyes off his upper body,” she recalls. “The épaulement of the head, the fluidity and articulation of the torso, the extension of his reach – that’s what struck me. It’s a very controlled solo.”

Dallas Black Dance reaches even further back into the black-dance canon for the politically and socially conscious Mourner’s Bench, set to the traditional spiritual, “There is a Balm in Gilead.” The best-known scene from Talley Beatty’s 1947 historical epic, Southern Landscape, loosely based on the racially motivated 1923 Rosewood massacre in Florida, is technically a solo. But the bench that the dancer mounts, crawls under and clings to for six minutes after returning from recovering a body is like another character.

“I knew Talley, and he always had a special message to deliver about the black experience in America,” Berry says. “The bench represents a safety zone, a foundation that harkens back to people who have come before us in the struggle. We’ve been lifted up, and we are reaching up and out of that horrific time. It’s about mourning, but it’s also a celebration.”

Just as Beatty and Ailey built on an African-American dance tradition with roots in the Harlem Renaissance, other black choreographers have been inspired by their work. Two of them, Troy Powell and Dianne McIntyre, are represented in the Cultural Awareness shows with pieces from the 2000s informed by the tradition’s major elements: West African and Caribbean movement vocabularies and African-American history.

Powell, artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater junior company, offers Lambarena (2002), a ballet-African dance mash-up set to a clever blend of Bach and Gabonese music. Lambarena does for eagles what Asadata Dafora’s 1932 classic Awassa Astridge did for ostriches. “Powell was inspired by the flight of birds he witnessed during a trip to Alaska,” Berry says.

Photo by Jaime Truman.

Meanwhile, Guggenheim Fellowship winner Dianne McIntyre, an independent dance-maker since closing her company, Sounds in Motion, in 1988, takes us on A Boundless Journey (2007) through African-American history, beginning with slavery. “From slavery to Jim Crow to civil rights – for me, that’s the journey in that work,” Berry says.

The Cultural Awareness program brings that journey up to the present with the premiere of Oremus, choreographed by Freeman, a 9-year veteran of Dallas Black Dance. Latin for prayer, it features all 12 dancers, who begin seated in chairs behind three long tables. “It’s an important work, I believe,” Berry says, the tables signifying another kind of safety zone partially inspired by the transition in leadership from company founder Ann Williams to Berry last September.

Over the course of Oremus, the performers move back and forth from the security of the barrier represented by the tables to their frustration and longing in the outside world. “Richard has something to say every year, and he has ideas that are relevant,” Berry says. “He doesn’t look to other choreographic voices. He’s original that way.”

—MANUEL MENDOZA