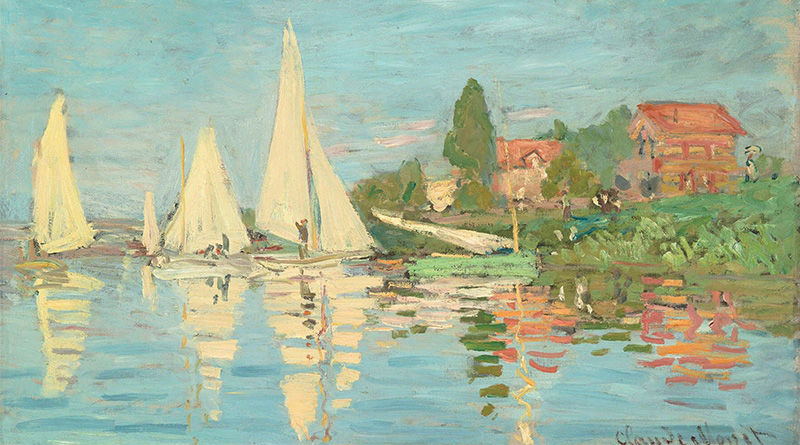

Claude Monet, Regatta at Argenteuil, c 1872. Oil on Canvas, 18 7/8 x 29 5/8 in. (48 x 75.3 cm). Musée d’Orsay.

Luncheon on the Grass (Central Panel), c. 1865-1866

Oil on Canvas

97 5/8 x 85 3/8 in. (248 x 217 cm)

Musée d’Orsay

Monet: The Early Years at the Kimbell Art Museum kicks off with a startling contrast between Claude Monet’s earliest exhibited work—View Near Rouelles, a crisp, placid, highly finished 1858 landscape—and Farmyard in Normandy (1863), which is striking for what exhibition curator George T. M. Shackelford notes is “a surface that, in its final form, appears to be still in progress.”

“Every corner of Farmyard in Normandy makes a show of the artist at work,” writes Shackelford, the Kimbell’s deputy director, in the fascinating catalog. “Rich umber browns are applied thinly and scraped through with a dry brush to create half tone and reflections in the pond’s surface at right, while the jagged branches of the tree … insist on revealing themselves, frankly, as slashes of pigment. And the incidental staffage—the cows, the farm boys, their ducks and chicken, their sketched-in dog—announce that Monet can paint.”

This “show of the artist at work” exposes three important things: that Monet, in achieving a “final” yet seemingly “in progress” surface, is becoming a modern painter; that he’s deliberately exposing his process—another modern preoccupation; and that yes, he’s announcing his talent and very much wants it to be noticed. As the exhibition makes clear, he’s becoming both Monet the ever-evolving artist and Monet the brand. Part of managing that brand throughout his career would include exhibiting works from the early years alongside more recent ones to survey his development and continuity.

The Wooden Bridge, 1872

Oil on canvas

21 1/2 x 28 3/4 in. (54 x 73 cm)

Private collection.

Through portraits of his newborn baby (1867) and of his wife on their honeymoon in Trouville (1870), we also see him becoming Monet the father and Monet the husband. A few months later, we meet Monet the Franco-Prussian War refugee, living in temporary exile in London, and in Holland, where he produced Houses by the Zaan (1871). Again, we see a variety of brushstrokes—medium for the clouds and sky, short and daub-like for the foliage, and hundreds of tapered, side-by-side strokes for the water, with tiny areas of white peeking through. The result, as Shackelford writes, is “one of the most complex and nuanced passages of reflected light in the painter’s oeuvre.”

Don’t fret that you’ll get shortchanged on masterpieces because of the show’s early dates. Monet the becomer knocked out quite a few. Shackelford has snagged many of them, including the delicate, sigh-inducing snowscape The Magpie (1869) and The Wooden Bridge (1872), which pushes reflected light, atmosphere and tensions between the painting’s vertical symmetry and horizontal asymmetry into an unlikely balance that, for Shackelford, looks to elements of Japanese printmaking while foreshadowing the more stripped-down 20th-century compositions of Kasimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian and Ellsworth Kelly.

La Grenouillère, 1869

Oil on canvas

29 3/8 x 39 1/4 in. (74.6 x 99.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929.

But this really is a show about Monet’s development, so we’re also treated to works that are rough around the edges but still intriguing, most notably Luncheon on the Grass (c. 1865-66), a monumental—though never completed—response to Édouard Manet’s masterpiece of the same name. Catalog contributor Mary Dailey Desmarais argues that Monet’s Luncheon also draws upon the Rococo master Jean-Antoine Watteau’s fêtes galantes and “reframes an elite social practice, the hunting party luncheon, as a popular pastime at a moment when the older tradition was being transformed by the influx of tourists to the forest of Fontainebleau.”

Luncheon, which includes an appearance by Gustave Courbet, literally got rough around the edges when, behind on his rent, Monet gave it as a security to his landlord, who rolled it up and let it mold in his cellar before the artist was able to redeem it. The two remaining fragments of the painting hang as an irregular diptych, with the damaged sections cut away from the top and bottom wider, now shorter right panel.

“I am much attached to this piece of work that is so incomplete and mutilated,” Monet told a visitor in 1920—a period the Kimbell will explore in 2018 in Monet: The Late Years. Small wonder: it plays with the forest’s extreme light and shadow in “almost unprecedented” ways, according to Shackelford, and it’s as good an example as any of the young Monet’s inventiveness and ambition. Make it your ambition to see this beautifully conceived and executed show before it closes Jan. 29.

—DEVON BRITT-DARBY