Life, love, and death. Each of these states of being is intrinsically tied to a process of transformation, molecular to ethereal, scientific to spiritual.

Today much of Robleto’s attention is focused on the Golden Record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images which Dr. Carl Sagan and other members of a NASA committee selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth. In 1977, NASA launched twin spacecraft Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, each with an identical copy of the record on board, intended as a message to other life forms outside our solar system.

As Voyager’s 50th launch anniversary draws near, Robleto says, “Now is the perfect time to ask some questions that I don’t think were asked the first time around, and that is essentially the topic of my third film.”

Central to Robleto’s research is Ann Druyan, creative director of the Golden Record. She and Sagan secretly fell in love while they were working on the project and announced their engagement two days after the Voyager launch.

“Ann was the only one to ask if human love should be included on the record. Humans falling in love, suddenly and illogically, is part of the human experience. That was hard to fit into a scientific mission; it wasn’t the right place for such sentiments. So she was driven to find another way to include them,” he says. His first two films, The Boundary of Life is Quietly Crossed (2019) and The Aorta of an Archivist (2020–2021), propose that Druyan literally snuck love on board in the language of her brain waves and heart waves.

“Part of my argument is that the Golden Record is the greatest work of art that art history has never accounted for. And I think Ann is our greatest avant-garde Feminist conceptual artist that nobody’s accounted for,” he says.

1 ⁄7

Dario Robleto, Photo by Sean Su Photography.

2 ⁄7

Dario Robleto (b. 1972), The Aorta of an Archivist, 2021, UHD video (53:00), Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

3⁄ 7

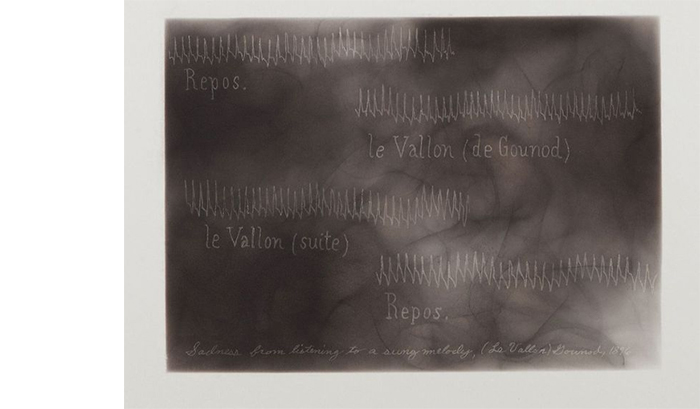

Dario Robleto, Sadness from Listening to a Sung Melody, (Le Vallon) Gounod, 1896, 2018, portfolio of 50 prints on Rising Drawing Bristol, photolithographs with transparent base ink, hand-flamed and sooted paper; image brushed with lithotine and lifted from soot, fused in a mild solution of shellac and denatured alcohol, Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

4 ⁄7

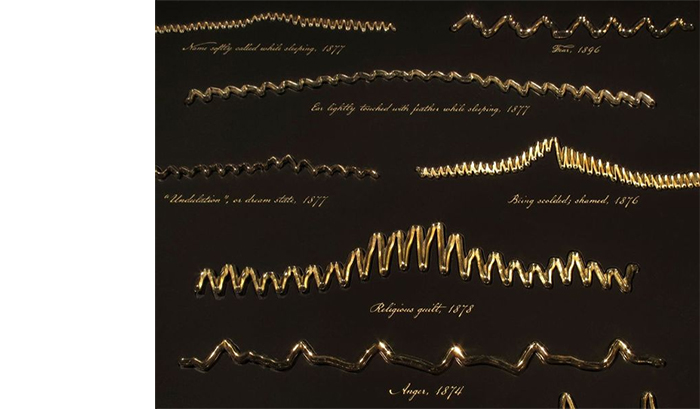

Dario Robleto, Unknown and Solitary Seas (Dreams and Emotions of the 19th Century), 2018, earliest waveform recordings of blood flowing from the heart and in the brain during sleep, dreaming, and various emotional states (1874–96), rendered and 3D printed in brass-plated stainless steel; lacquered maple, and 22k gold leaf, Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

5 ⁄7

Dario Robleto (b. 1972), Unknown and Solitary Seas(Dreams and Emotions of the 19th Century) (detail), 2018, earliest waveform recordings of blood flowing from the heart and in the brain during sleep, dreaming, and various emotional states (1874–96), rendered and 3D printed in brass-plated stainless steel; lacquered maple, and 22k gold leaf, Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

6 ⁄7

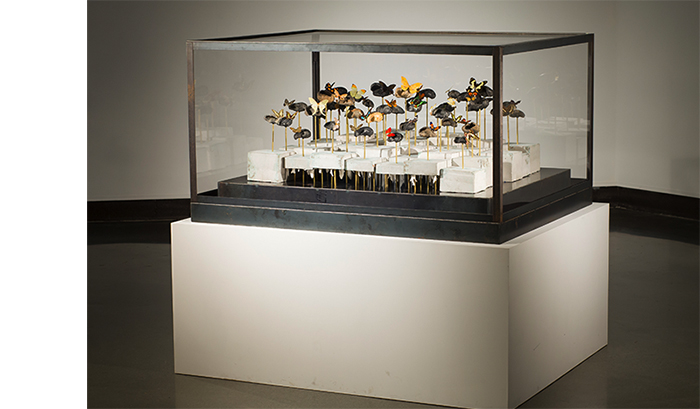

Dario Robleto (b. 1972), American Seabed, 2014, fossilized prehistoric whale ear bones salvaged from the sea (1 to 10 million years), various butterflies, butterfly antennae made from stretched and pulled audiotape recordings of Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row,” concrete, ocean water, pigments, coral, brass, steel, Plexiglas, Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

7 ⁄7

Dario Robleto (b. 1972), American Seabed (detail), 2014, fossilized prehistoric whale ear bones salvaged from the sea (1 to 10 million years), various butterflies, butterfly antennae made from stretched and pulled audiotape recordings of Bob Dylan’s “Desolation Row,” concrete, ocean water, pigments, coral, brass, steel, Plexiglas, Courtesy of the artist, © Dario Robleto

At the time, Gaisberg had in his hands what would have been cutting-edge portable field recording technology, a new tool of historical documentation. He is of the generation that introduced the term “the war to end all wars” in response to the death and destruction. He believed it was his ethical obligation to make the final recording of war—an endeavor poignantly similar to that of the Golden Record, even though it wasn’t off-planet.

Ultimately the NASA team decided against including the rare recording, but it inspired Druyan to ask deeper questions about if they should consider including a wider range of what humanity is capable of, the good and the bad.

And so part of what Robleto’s Ancient Beacons Long for Notice explores is Druyan’s meditations not just about love but about war, and more broadly, the ways we undermine ourselves as a species through poverty or environmental destruction or various forms of bigotry and tyranny.

“I argue that this is the most important record that didn’t make it on the Golden Record. It provokes an even deeper question about our moral obligation for a full accounting of humanity’s actions,” says Robleto. “Once again Ann did something so radical that until now no one knew about. She didn’t just sneak love on board, she snuck war on board.”

Structurally, Ancient Beacons Long for Notice gives some basic nods to the one-hour public television science film format and techniques, such as narration and pacing, chapters and casting (think: 1980 PBS documentary series Cosmos, which Duyan co-wrote and Sagan hosted). But this is not your typical documentary film—it goes into some pretty unusual places. Viewers can expect to see a combination of archival footage from World War I and original NASA space probe footage merged with Robleto’s own special effects, animations, and other elaborate visual compositions, including trying to convey to the viewer what’s inside the grooves of a record. And what sounds like static is in fact Druyan’s EKG and EEG recordings as she reflects on falling in love, along with contemplating environmental devastation, poverty, war, and a full range of other human experience and actions.

We tend to associate the heartbeat with signs of life, even when the rhythm is mechanically or technologically generated. For example, last August the press reported that NASA had picked up Voyager 2’s “heartbeat signal” after temporarily losing contact with the craft. Not only is the heart a complex organ, it is a complicated idea to wrap our minds around.

Included in that gift, and the exhibition, is The First Time, the Heart (A Portrait of Life 1854–1913) (2018), a photolithograph portfolio of heartbeat waveform recordings from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For example, Sadness from Listening to a Sung Melody, (Le Vallon) Gounod depicts a person’s heartbeat while listening to music. The portfolio includes other impressions—apparition-like images created from hand-flamed and soot on paper—of “Smelling lavender” and “Young lady, 28, much debilitated by prolonged mental work, the entertainment of company, and the cares of a large household.” The poetics are almost heartbreaking.

One of the stipulations that comes with exhibiting the print portfolio is that every time it’s shown, Robleto invites someone else to resequence them. At the suggestion of the Carter’s curator Margaret Adler, the artist invited NASA astronaut John Herrington to collaborate with him on the museum presentation of the prints. Herrington is the first Native American to enter space as a flight engineer aboard the Endeavour space shuttle in 2002.

“My central question is, and has been, what is one gift I can give to the only woman whose heart has left the solar system? I’m asking this question religiously, philosophically, scientifically, from every point of view. And so the book, the films, sculptures, and prints… all of it is my humble attempt to answer this question. I don’t know that it can ever be fully answered, but I’m trying and part of that trying is the creation of the artwork.”

—NANCY ZASTUDIL