People often consider abstraction to be the absence of content, the erasure of reference. Within art, we experience an inherent tug of war between abstraction and figuration – which is difficult or simple to comprehend and recognize. But abstraction, even when seemingly incomprehensible, can be both grounding and universal, opening the mind to a broader perspective while rooting us in place and time.

Abstraction allows artists to seize these insular moments, contemplating and enriching their connection to a larger experience. Artists are tethered to the same social currents of the world they occupy, and like everyone else, they are drawn to these cosmic currents.

In the exhibition Joe Overstreet: Taking Flight, on view from Jan. 24 – July 13, 2025, the Menil Collection highlights Overstreet (1933–2019), an artist renowned for striving to intertwine abstraction and social politics.

For decades, though, the Flight Patterns series – central to this exhibition – had never been on view at the museum.

“In 2018, we were undertaking a major renovation of the main building and, in that connection, had the opportunity to revisit these incredible paintings,” Dupêcher explained. “We installed two Flight Patterns in our contemporary art galleries and visited the artist in his longtime studio, on New York’s East 2nd Street, several times. Sadly, Overstreet passed away in 2019, but he knew of our interest in mounting this major exhibition devoted to his work. We can’t wait for the public to discover his visually stunning, deeply meaningful art.”

Throughout his six-decade career, Overstreet established himself as an organizer and a vital painter in the postwar era of American art, consistently and unflinchingly bringing issues of racism and inequality to the forefront as he moved through the artistic, political, and cultural movements of the times.

1 ⁄6

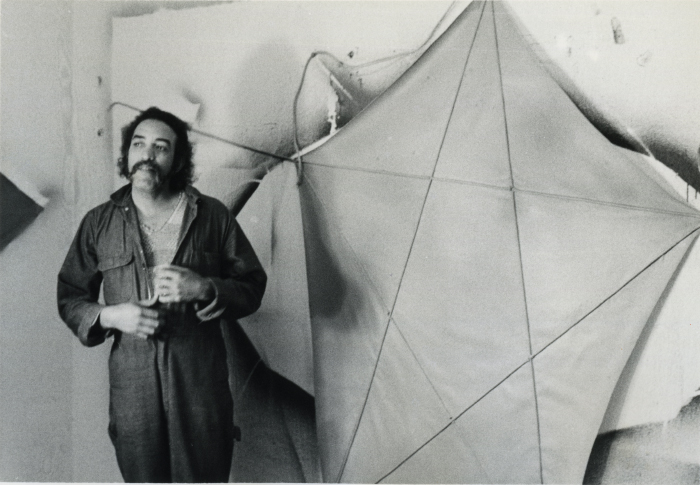

Joe Overstreet with his Flight Patterns, 1972. Courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Hickey-Robertson, Houston.

2 ⁄6

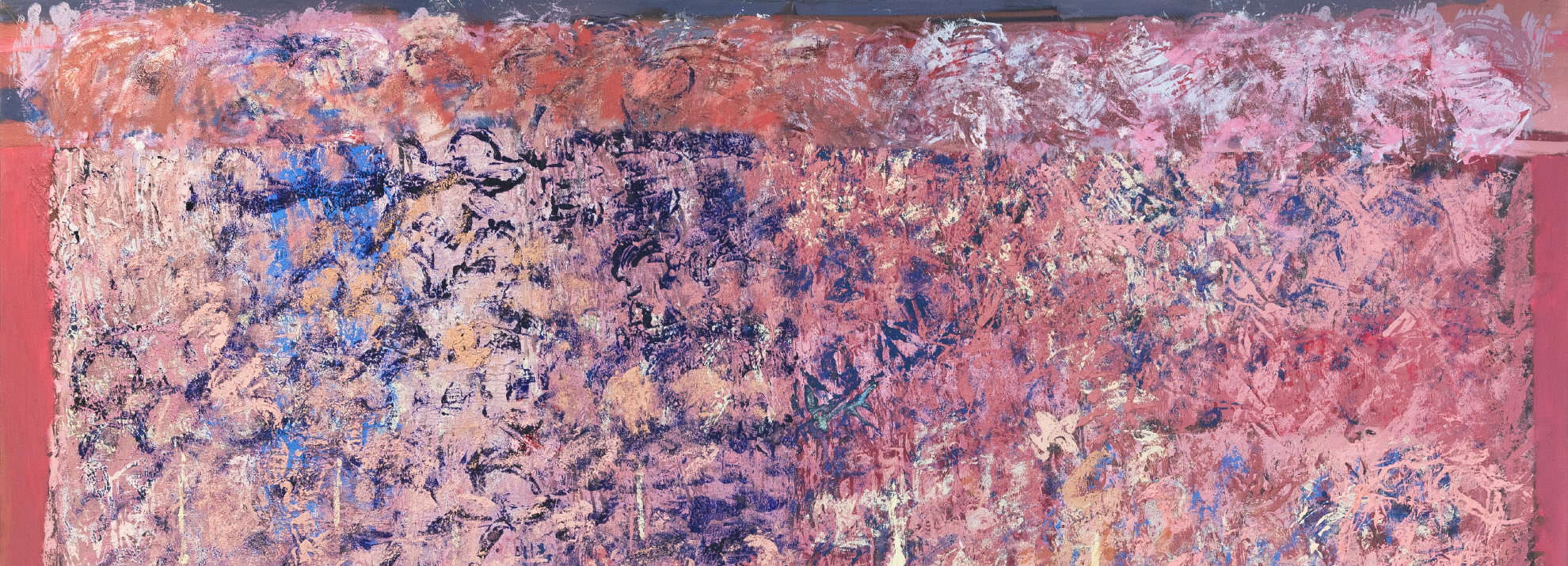

Joe Overstreet, HooDoo Mandala, 1970. Acrylic on canvas with metal grommets and cotton rope, 90 × 89 1/2 in. (228.6 × 227.3 cm). Neil Lane Collection. © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Jenny Gorman.

3 ⁄6

Joe Overstreet, Great Mother of All, 1970. Acrylic on canvas with metal grommets and cotton rope, 115 × 195 × 65 in. (292.1 × 495.3 × 165.1 cm) (present installation dimensions). © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Samuel Glass.

4 ⁄6

Joe Overstreet, Free Direction, 1971. Acrylic on canvas with metal grommets and cotton rope, 89 x 131 x 22 ½ in. (226.1 x 332.7 x 57.1 cm) (canvas size). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Paul Hester.

5 ⁄6

Joe Overstreet, Evolution, 1970. Acrylic on canvas with metal grommets and cotton rope, 115 ½ × 97 in. (293.4 × 246.4 cm). Lent by the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Mary and Bob Mersky. © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Jenny Gorman.

6 ⁄6

Joe Overstreet, Gorée, 1993. Oil on canvas, 120 × 144 in. (304.8 × 365.8 cm). © Estate of Joe Overstreet/Artist Rights Society (ARS), courtesy of Eric Firestone Gallery, New York. Photo: Samuel Glass.

Of his own work, Overstreet once explained in an artist statement, “My paintings don’t let the onlooker glance over them, but rather take them deeply into them and let them out—many times by different routes. These trips are taken sometimes subtly and sometimes suddenly.”

Over the course of his career, Overstreet worked in multiple modes, resisting simple summation. Flight Patterns is a series of gloriously colorful abstract pieces inspired by Tantric drawings and Navajo sand painting. He began making them in 1970 on shaped canvases that he attached to walls, floors, and ceilings by running ropes through holes at their edges, giving them the appearance of flight.

“Overstreet is best known for his Flight Patterns, but we have included important bodies of work that precede and follow that series,” Dupêcher said. “He was among a cohort of young artists intrigued by the possibilities of a non-rectangular picture format.”

“Overstreet participated in those discussions and drew inspiration from, in his words, ‘African systems of design, mythology and philosophy.’”

In the early 1990s, Overstreet visited Dakar, Senegal, spending time on Goreé Island. He was so moved by the experience that he created a series called Facing the Door of No Return, a group of monumental abstract paintings.

“He described these works as ‘emotional examinations of my past, present and future,’ memorializing his own ancestral story and the centuries of history that passed through the Door of No Return,” Dupêcher said. “Taken together, all of these artworks demonstrate the political power of abstraction, as well as the artist’s ceaseless appetite for experimentation.”

“Art is made by artists,” she said, “and there are hundreds of ways in which all art forms, including abstraction, are shaped and molded by the lived identities and experiences of their maker.”

-MICHAEL McFADDEN