Stop reading for a second and close your eyes. What do you see? In an instant, as in prayer or any meditative practice, you may sense that your body—its limbs, hair, skin, and bones—is no longer a solid, humanoid form, but something more akin to the ether, and connected to the transcendent.

From Sept. 13, 2025, to Jan. 4, 2026, the Nasher presents the first major museum survey of Gormley’s work in the United States, including early, experimental works stretching back to the 1980s, sculptures, maquettes, sketchbooks, and a new, major public installation that will transform the skyline of the Downtown Dallas Arts District.

Connecting the works in Survey is Gormley’s gift for creating an interactive, physical experience for the viewer, where the sculptures seem to respond to humans in the room, while provoking what he describes as the “imaginative freedom” to enjoy an experience beyond one’s senses. (Gormley’s interest in Buddhism and Vipassanā meditation dates back to the early 1970s and has informed his work to the present day.)

1 ⁄6

Antony Gormley, 2022. Photograph by John O’Rourke.

2 ⁄6

Antony Gormley, FLOOR, 1981. Rubber.9c 1/4 x 48 x 52 3/4 inches (0.6 x 122 x 134 cm). © Antony Gormley. Photograph by Stephen White & Co., courtesy of the artist.

3 ⁄6

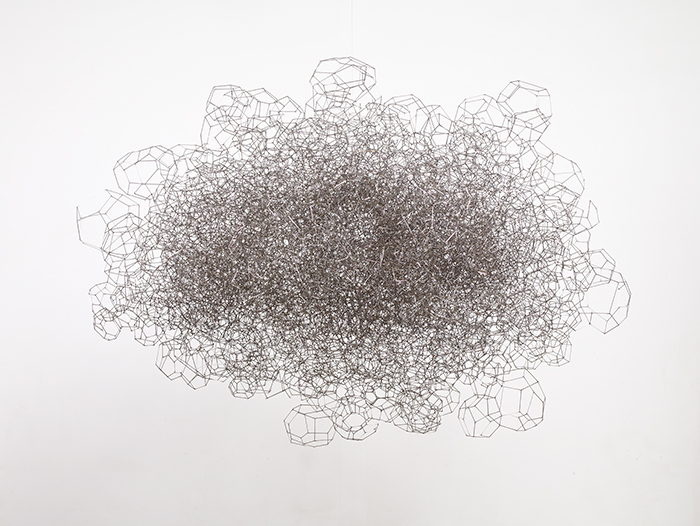

Antony Gormley, DRIFT VI, 2010. 2 mm square section stainless steel bar. 84 3/4 x 89 3/4 x 122 3/4 inches (215 x 228 x 312 cm). © Antony Gormley. Photograph by Stephen White & Co., courtesy of the artist.

4 ⁄6

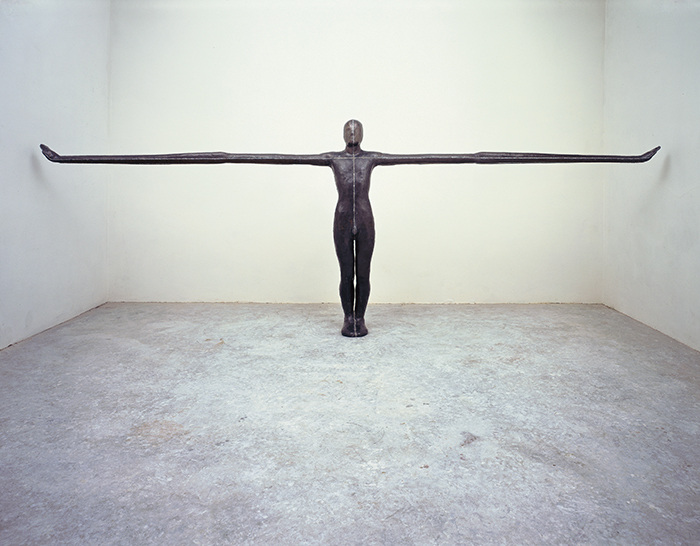

Antony Gormley, CLOSE V, 1998. Cast iron. 10 3/4 x 79 1/4 x 68 1/2 inches (27 x 201 x 174 cm). © Antony Gormley. Photograph by Stephen White & Co., courtesy of the artist.

5 ⁄6

Antony Gormley, Pile I, 2017. Clay. 14 3/4 x 29 x 27 1/2 inches (37.4 x 73.5 x 69.7 cm). Installation view of Essere, Le Gallerie Degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy, 2019. © Antony Gormley. Courtesy of Galleria Continua. Photograph by Ela Bialkowska, OKNO STUDIO.

6 ⁄6

Antony Gormley, FIELD, 1984–1985. Lead, fiberglass, plaster, and air. 77 1/4 x 217 x 16 1/2 inches (196 x 551 x 42 cm). © Antony Gormley. © Antony Gormley. Photograph by Antony Gormley, courtesy of the artist.

Those parts include the new public project—sculptures that are life-size silhouettes of recognizably human figures made up of an open network of stainless-steel bars and installed on buildings visible from the Nasher’s garden. These gleaming sculptures, each the size of Gormley—who is 6’4” and throughout his career has been the model for his work—hover above the viewer and seem to touch the sky. And you can see through them. The dispersal of these figures is a response to the conditions of the body in the ever-evolving digital world that humans continue to navigate. “The figure being reduced to a field of energy is an expression of that experience,” says Morse. “It references the built environment, the digital world, and transcendent experiences.”

Over the course of his career, Gromley’s body forms have become more geometric and abstract, drawing on architectural vocabulary of the “built environment” to create figures that, as in his series Shift, at first glance look like the missing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, but upon closer inspection, could also be figures in repose, or segmented portions of a long buried, now unearthed metropolis. (Interestingly, as his sensitivity to the carbon footprint of art-making has grown, Gormley has stopped using concrete, the material for these “blockworks” and bunkers.)

When asked, Morse confirms Gormley is, indeed, “down-to-earth,” and believes anyone can engage and experience something meaningful with his work, regardless of their knowledge of art or art history. “Part of that is the accessibility of the human figure,” says Morse. “That sense of being able to put ourselves in that place and stand outside of it is something that makes the work eminently relatable.”

—CHRIS BECKER