It’s doubtful that a mystic Carmelite nun was the inspiration for scientists at the German company Merck when they developed 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known as ecstasy and molly, in 1912.

What is clear is that had Phillip Townsend not learned about Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s marble sculpture The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, where an angel’s bow pierces her heart and leads her to collapse, we may not have been gifted with the new exhibit Transcendence: A Century of Black Queer Ecstasy, 1924-2024 on display at the Art Galleries at Black Studies at The University of Texas at Austin through May 9. (Artwork in a third venue, the Visual Arts Center, came down on March 8 to accommodate graduate art student exhibits.)

Townsend is an instructor and the curator of the galleries. What makes the space different is that it is not affiliated with the College of Fine Arts but instead the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies in the College of Liberal Arts, showing how art is part of the fabric of every discipline.

“Ecstasy is one of those things that hasn’t really circulated within public discourse in a way that the general public is familiar with,” he said.

So, no surprise: “The first thing people asked me about the show was, ‘is this about people taking ecstasy?’ And of course I’m like, ‘no, no,’” he said. “But I didn’t want to shy away from these physical and mind-altering states. That has to be included with any conversation about ecstasy.”

The 59 works of art and ephemera cover a transformative century for art and society, with the emergence of new media such as photography and video overlapping with the struggle for Black and queer recognition. Divided into seven themes, his approach includes art that connects to the crux of the show (objects by Black and queer artists), how ecstasy is conveyed (by Black but maybe not queer artists) and the relationships between the artists and subject.

1 ⁄9

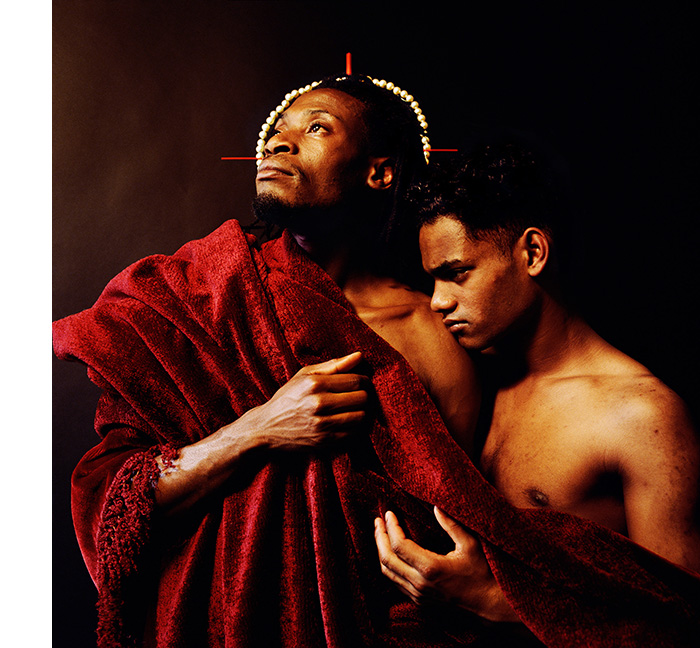

Bre’Ann White, Deity II, 2015. Inkjet print, 48 x 36 in. Courtesy of the artist © Bre’Ann White

2 ⁄9

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies), 1989. C-Type archival print, 20 x 24 in. Courtesy of Autograph, London © Rotimi Fani-Kayode

3 ⁄9

Didier William, Tender, 2024. Woodblock print on French Paper Brand 100lb., 31 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist © Didier William

4 ⁄9

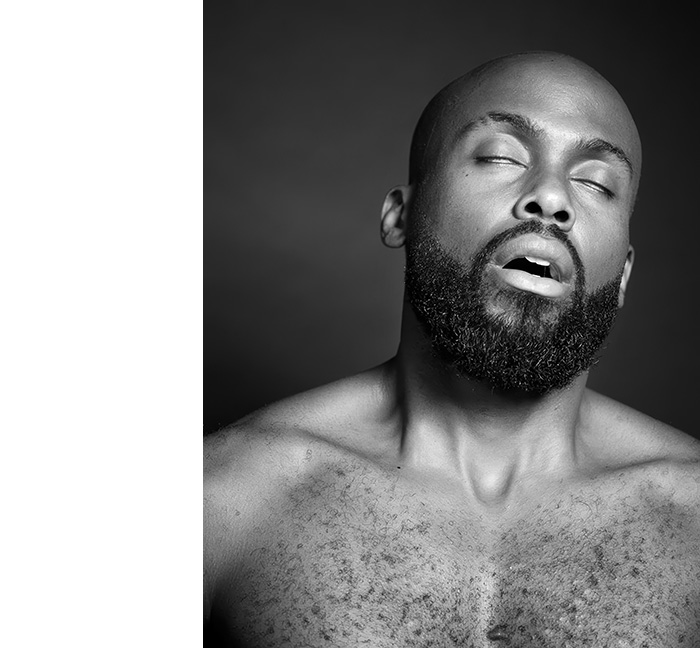

Ajamu X, Dwayne, 2012. Platinum print, 9 x 13 in. Courtesy of the artist © Ajamu X

5 ⁄9

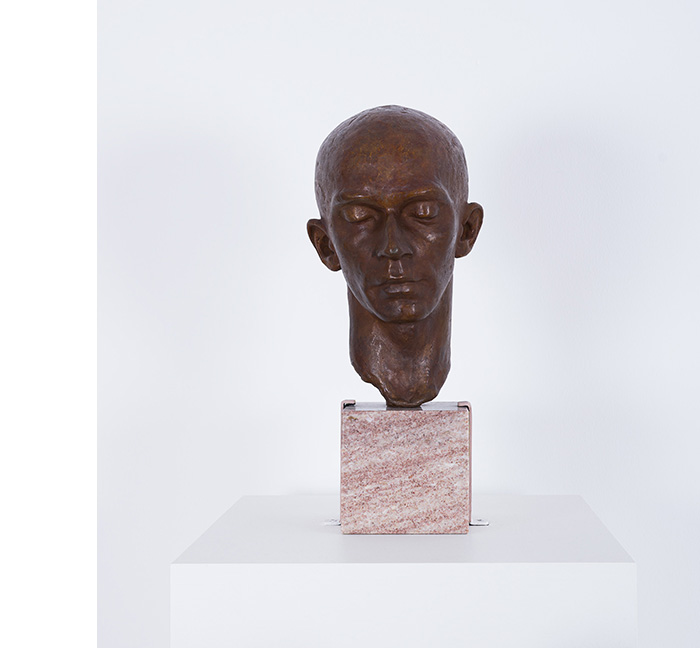

Richmond Barthé, Head of a Dancer: Harald Kreutzberg, circa 1933. Bronze on original stone base, overall: 12 1/2 × 7 3/8 × 6 1/8 in. (31.8 × 18.7 × 15.6 cm), additional Dimension: 4 3/4 × 5 × 5 in. (12.1 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm). Courtesy of Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, Purchase through the generosity of Tom and Carmel Borders and Jeanne and Michael Klein, 2017.25

6 ⁄9

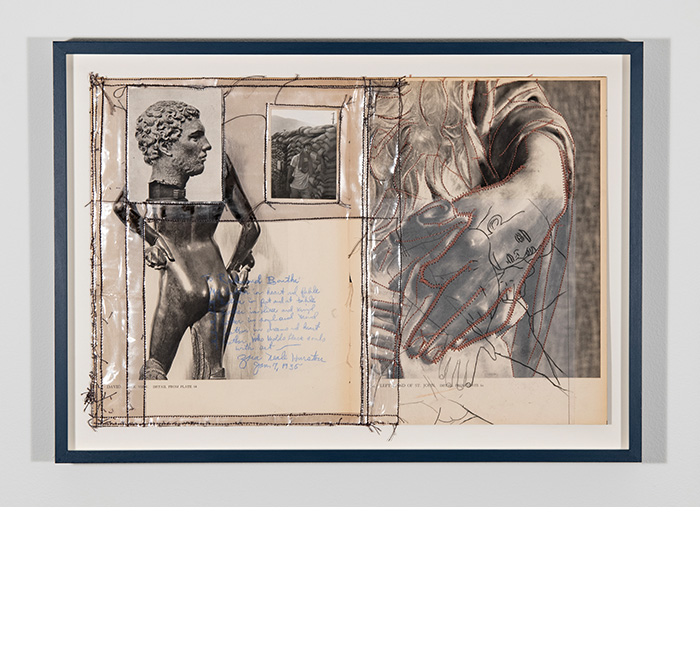

Troy Montes Michie, Half High (Traces in Ecstasy), 2024. Mixed media on paper, 13 x 17.5 in. Courtesy of the artist and Company Gallery, New York © Troy Montes Michie. Photo: Mark Doroba

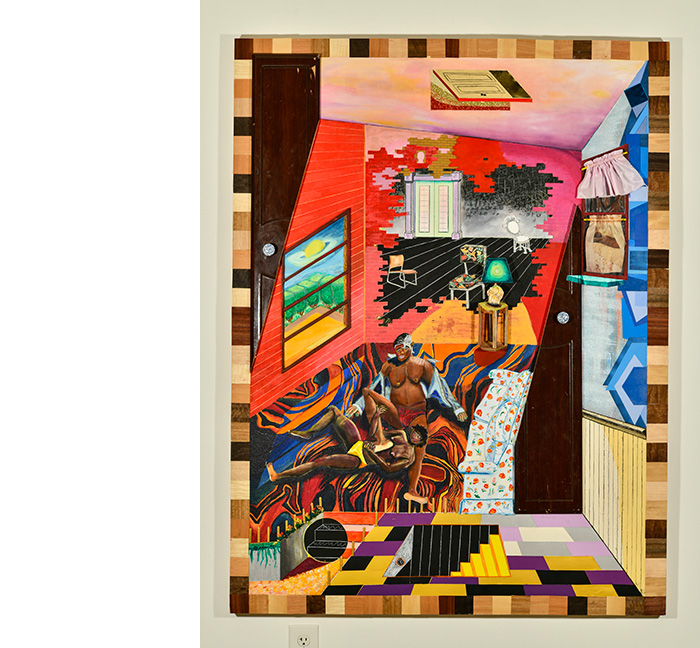

7 ⁄9

Devin N. Morris, 3:33 pm "This Might Be A Light Worker You Know", 2019. Acrylic, oil pastel, collage, foam core, wood veneer, cabinet door, ceramic door knob, inkjet print on silk, polyester. Courtesy of Carolyn Ramo, New York. © Devin Morris. Photo credit: Mark Doroba

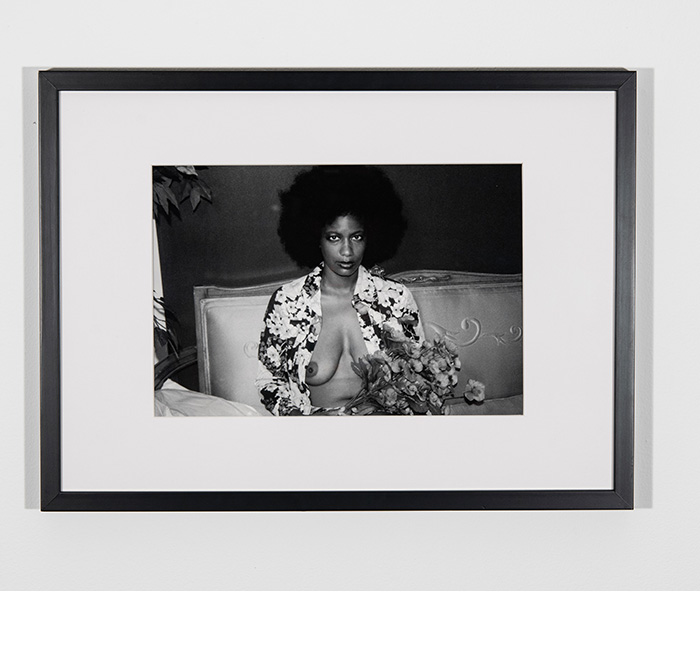

8 ⁄9

Mickalene Thomas, Afro Muse #5 in Black and White, 2005. Selenium-toned fiber print, 10 x 15 in. Courtesy of Leslie Lohman Museum, Foundation purchase with funds provided by Richard Gerrig and Timothy Peterson, Alix L.L. Richie and Marty Davis © Mickalene Thomas. Photo: Mark Doroba

9 ⁄9

Beauford Delaney, Untitled, 1960. Watercolor, gouache, and sand on paper, 27 1/2 x 19 1/2 in. Courtesy of Knoxville Museum of Art, 2014 purchase with funds provided by the Rachael Patterson Young Art Acquisition Reserve, 2014.13.08

Troy Montes Michie, who was born in El Paso, created a new piece for the show, the mixed media painting Half High (Traces in Ecstasy) (2024). In it, a drawing of an ancient bust covers the top of a naked sculpture with a close up of a hand of presumably a female statue covering the stomach. Drawn in is a sleeping person.

“It’s incredible and responds to the themes of the show perfectly,” Townsend said.

It engages with Richmond Barthé, whose bronze bust Head of a Dancer: Harald Kreutzberg (c. 1933), appears in the section Portraiture, and peripherally with one an edition of the magazine FIRE!! Devoted to Young Negro Artists printed in 1926. Zora Neale Hurston, who was a contributor to the magazine later wrote an ode to Barthé, excerpts from which Montes-Michie includes in his piece. The inclusion may be a stretch. But broad connections are foundational to the show’s themes, which create a framework for future shows and push the viewer to rethink about types of art. Among the 12 works chosen for the theme Portraiture, for instance, are Barthé’s bust alongside Mickalene Thomas’s photograph Afro Muse #5 in Black and White (2005). It’s a small yet bold photograph of a woman with seductive eyes, a stone cold face and an unbuttoned shirt with her breasts exposed.

Barthé and Kreutzberg were driven by emotion, as was Beauford Delaney, whose Untitled (1960) appears in the show. The pioneering abstractionist’s paintings are full of drama. “He used color and was thinking about human emotion and expression,” Townsend said.

With 3:33 pm “This Might Be A Light Worker You Know” (2019), Damien N. Davis rebuilds his childhood homes while considering illicit desire, strong emotion and being out and queer. Davis’s large sculptural work adds to another result of ecstasy of liberation and fulfillment. It is among the subjects in Black Queer Futures, a small selection of new works by younger artists. “These artists are thinking about spaces and different planes and alternative ways of imagining themselves existing in a space where they could live their fully self-expressed lives,” he said, perhaps setting the stage, too, for future exhibitions.

—JAMES RUSSELL