Known for its stellar collection of American art, the Amon Carter Museum in Fort Worth is expanding the definition of what art and artists from the United States could be.

Originally curated by Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander (Stanford’s Robert M. and Ruth L. Halperin Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art and Co-Director of the Asian American Art Initiative), the exhibition served as the inaugural show of the initiative and came about from a fortuitous acquisition of a San Franciscan patron’s private collection.

“One of the reasons we co-founded the AAAI at Stanford was because of the long history of Asian American presence in the Bay Area,” says Alexander. “We acquired a significant amount of work from art dealer and collector Michael Brown, who had spent a lot of his life gathering work from artists of Asian descent living and working in California. The exhibition came out of looking at the different types of stories these objects could tell.”

“It wasn’t just for Stanford,” Alexander emphasizes. “It was for a Bay Area audience who are familiar with San Francisco’s Chinatown. It’s the oldest Chinatown in America, and a lot of these artists were based here. I was making sure I made these stories accessible to people who are familiar with our history.”

The curator’s initial goal was expanding public awareness, citing the lack of Asian American museum collections across the country. Tailored to a more academically inclined audience, Alexander initially divided “East of the Pacific” into six thematic sections, arranged “vaguely chronologically.”

First, she examined “discreet points of contact from 19th-century immigration history, beginning when Japan opened itself for trade, which allowed artists to go back and forth across the Pacific, and an early influx of Chinese immigrants to the United States.”

1 ⁄6

Wing Kwong Tse (Chinese, active USA, 1902–1993), Hands, ca. 1970s, watercolor on paper, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. The Michael Donald Brown Collection, made possible by the William Alden Campbell and Martha Campbell Art Acquisition Fund and the Asian American Art Initiative Acquisitions Fund, 2020.123, © Wing Kwong Tse Estate

2 ⁄6

Tokio Ueyama (American, b. Japan, 1889–1954), Monterey Cove, 1924, oil on canvas, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. The Michael Donald Brown Collection, made possible by the William Alden Campbell and Martha Campbell

Art Acquisition Fund and the Asian American Art Initiative Acquisitions Fund, 2020.129

3 ⁄6

Toshiko Takaezu (American, 1922–2011), #8, ca. 1990s, stoneware with glazes, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of the artist, 2008.230, © Toshiko Takaezu

4 ⁄6

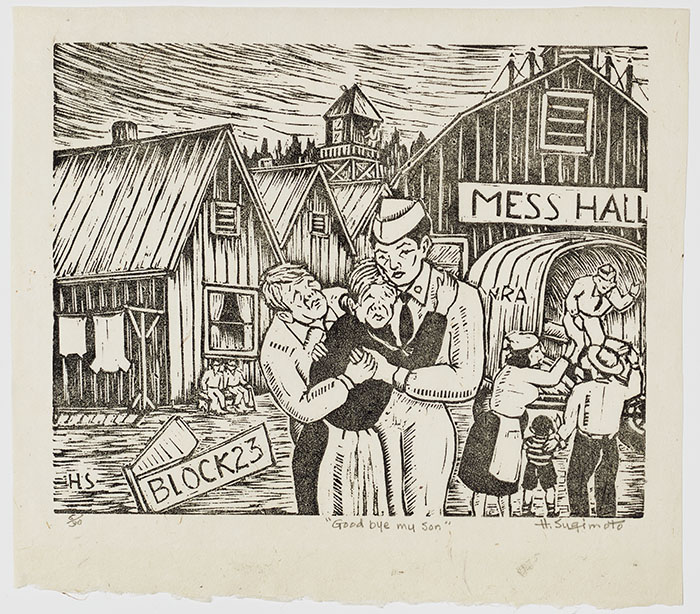

Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto (American, b. Japan, 1900–1990), Goodbye My Son, ca. 1965, linocut, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of Patrick and Sandra Hayashi in support of the Asian American Art Initiative, 2021.105, © Henry Yuzuru Sugimoto Estate

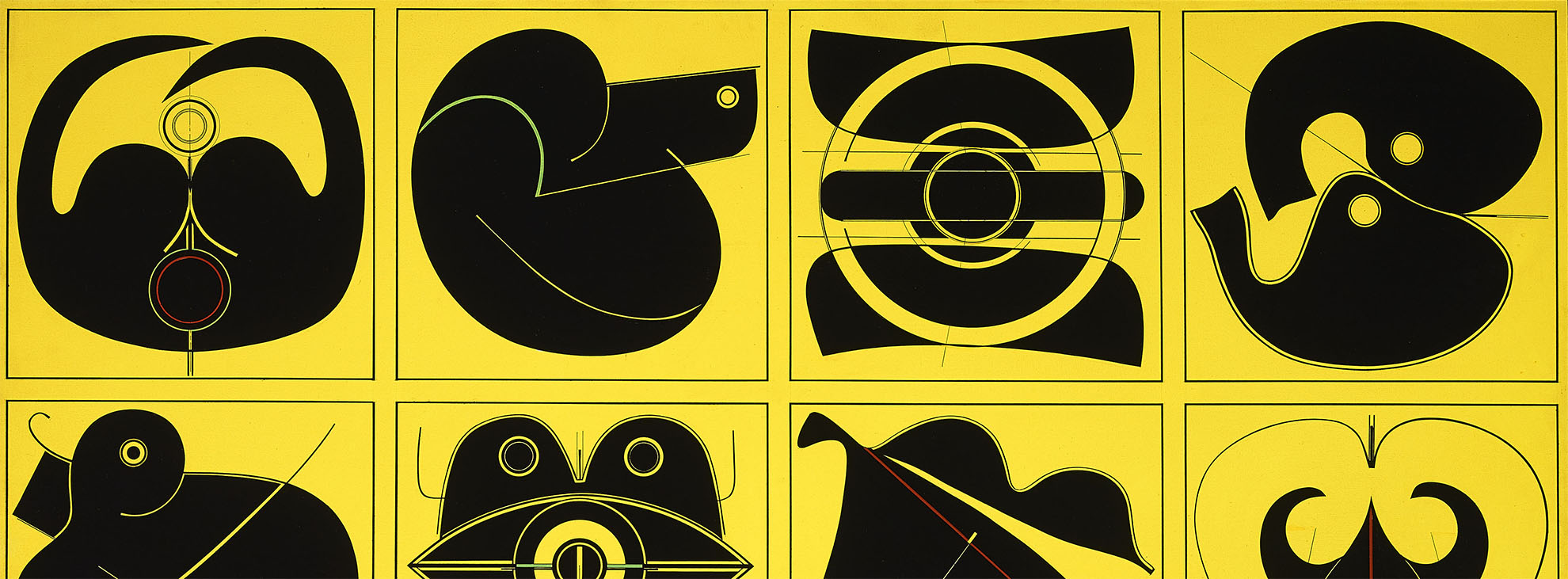

5 ⁄6

Roger Shimomura (American, b. 1939), Lush Life #2, 2008, acrylic on canvas, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. Gift of Marilynn and Carl Thoma, 2010.97, © Roger Shimomura

6 ⁄6

Takeshi Kawashima (Japanese, active USA, b. 1930) New York Series, 1967, oil on canvas, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University. The Michael Donald Brown Collection, made possible by the William Alden Campbell and Martha Campbell Art Acquisition Fund and the Asian American Art Initiative Acquisitions Fund. Funding for the conservation of this artwork was generously provided through a grant from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, 2020.69, © Takeshi Kawashima

Perhaps the most powerful gallery explored citizens placed in Japanese-American camps during World War II and the artists working within them. The fifth had a selection of nonrepresentational works to rival the more obvious white male figures of the abstract expressionist movement, such as Pollock and Rothko.

Finally, the last section reflects on the 1976 exhibition“Other Sources: An American Essay” mounted on the occasion of the Bicentennial at the San Francisco Art Institute. Creating a new canon of art to juxtapose the white Western canon, it included blue chip names like modernist sculptor Ruth Asawa.

Staged at the Carter in a smaller format with 48 objects and wall text tailored to a more general audience less familiar with California art and history, it builds on the Fort Worth museum’s mission to widen the boundaries of what viewers perceive as “American art.”

As the Carter is the only venue outside of San Francisco to stage East of the Pacific, the work it highlights is exemplary of the museum’s mission, according to Michaela Haffner, the museum’s assistant curator of painting, sculptures, and works on paper.

Haffner feels that aligning the Trans-Pacific story with the conquering of the American West, so often depicted in Carter’s permanent collection, will make perfect sense to even the most casual of art lovers.

“The Trans-Pacific context is one of migration and immigration, and the stories of what happened in the 19th and 20th century connect us as our state is also one of migration and immigration,” she says.

“It would have made a huge difference to me as a young art history student to see an exhibition like this, so I hope (this show) can be that opportunity for someone else,” says Alexander, “Frankly to just be able to get the work out there is a huge battle and an important piece of the puzzle when it comes to telling a more diverse, inclusive, and, importantly, accurate history of American art.”

—KENDALL MORGAN