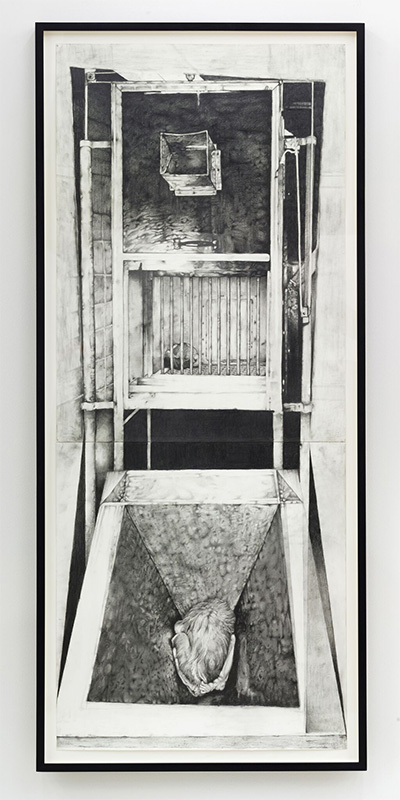

Installation view, Lionel Maunz: Discovery of Honey / Work of the Family, The Contemporary Austin – Gatehouse Gallery at the Betty and Edward Marcus Sculpture Park at Laguna Gloria, 2017.

Artwork © Lionel Maunz. Courtesy the artist and Bureau, New York. Image courtesy The Contemporary Austin. Photograph by Colin Doyle.

Exploring the aesthetics of self-destruction, Lionel Maunz uses cast iron, concrete, and steel to create dystopian figurative sculptures—surprisingly organic forms that appear distorted by dismemberment and decay. His current exhibition, Discovery of Honey / Work of the Family, which he describes as a “personal interrogation of childhood and parenthood,” is on view through May 14 at The Contemporary Austin.

Maunz is inspired by classical art, exploring gothic themes of fear, violence and religion. Ineffably troubling and provocative, his work is decidedly more intuitive than rational, and his grotesque figures are somewhat comparable to the most unsettling imagery of Hieronymus Bosch.

The pieces in this show are so heavy that Maunz used an engine hoist to move them around his studio. Most of the figures have simple geometric concrete bases reminiscent of monuments and minimalist architecture but seeing his sculpture hanging from the hoist compelled him to add elements of suspension. At one point, he looked up at a work and it made him think of a hive, which reminded him of Piero di Cosimo’s religious painting The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus. “I sort of hate that painting,” Maunz admits. “It’s a heavy-handed allegory.”

He also thought of Albrecht Dürer’s apocalyptic woodcut St. John Devouring the Book which depicts an angel with a body of fire and pillars for legs feeding St. John a manuscript of the The Book of Revelation with its predictions of violent turmoil. Maunz remembered a passage from Revelation: “It shall make thy belly bitter, but it shall be in thy mouth sweet as honey.”

With these references to honey in mind, he decided to create a unified theme for the show. Originally planned as a family group with two parents and three children, he split up them up, removing a couple figures entirely and slicing some of others apart.

The hive is also a reference to community. “In my last solo show in New York I did a drawing of a woman with a hive in her abdomen,” he says. “I grew up in a hermetic community that left a bad taste in my mouth. I have an innate hostility towards community, which I reference with the hive. Honey is the byproduct, a repulsive excrescence.”

But Maunz prefers not to elaborate further on the circumstances of his upbringing. “It’s an easy in for a viewer,” he says. “It sets up this victim complex, which people can claim to relate to. It gives a really loaded entrance to the work, which can obscure other things I am interested in. I just want to avoid that reading.”

His work is viscerally exciting and repulsive, emotional and emotionless. “I’m not trying to create a unified whole or a holistic connection out of these polarities,” he says. “I’m just really trying to excite tension and keep it constantly circling in this vortex without resolution.”

Maunz was initially trained as a painter at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and now lives in New York. He grew up drawing “cars and dead bodies,” but didn’t take a career as an artist seriously until his professors encouraged him to pursue the violent imagery that interested him. “If something excites me, it stays with me,” he says.

And excitement does not seem to come easily for him. He credits a “burn reconstruction medical textbook” as a source of inspiration. He also acknowledges R.D. Laing’s writings on psychosis, Harry Harlow’s social isolation experiments on primates, and Peter Sotos’s examinations of sadistic sexual criminals.

The sculptures in Discovery of Honey / Work of the Family are accompanied by Maunz’s drawings, which are even more direct and representational. Black River is a festering image of a rotting baby protruding from a womb sitting on a primitive delivery platform. The mother’s legs are amputated at the knees and nothing else remains of her body.

“I used to do more drawings,” he says. “They always seemed to be ahead of the sculptures because it was difficult working with the figure in three dimensions. But in the last few years the sculpture has caught up with it and it’s no longer a regular part of my studio practice. I generally only work on them for specific shows.”

Discovery of Honey is a sculpture of a child strung up by his feet. Annunciation is a sculpture of a beheaded boy. The Contemporary Austin commissioned Lick Your Throat and Cut Your Feet for the Betty and Edward Marcus Sculpture Park. It looks like a monument made out of random body parts.

“These bodies in pain and violence towards them,” Maunz says. “It’s often in my mind. Not a clinical or rational body, but a cacophonous experiential body that spasms. So much of that complex we call an individual is all this desperation and confusion, this tangle of exteriority and interiority. I try to confuse or collapse that dichotomy.”

He seems to find a physical body with a consciousness irreconcilable.

“It’s an innately cruel relationship between the body and mind,” Maunz says. “It’s so amorphous and these hierarchies between one and the other are constantly flipping. Demands and desires are often of the body and our fugitive minds often refuse to engage in the right way.”

—JEREMY HALLOCK