A curtain lifts. A dancer moves across the stage, costume fluttering around graceful limbs. A sail catches the ocean breeze. In Robert Rauschenberg: Fabric Works of the 1970s, opening at the Menil Collection Sept.19, 2025 and on view through March 1, 2026, the late artist’s softest, most ephemeral creations take center stage, hovering, swaying, translucent in form, persistent in vision.

“The Menil Collection wanted to commemorate the artist’s centennial year, so I was looking at exhibitions that would highlight underrepresented work,” said Michelle White, Senior Curator at the Menil Collection. “I found these fabric works incredibly compelling visually and historically in how they confront Rauschenberg’s work, how they are unexpected and beautiful compared to the other works he created throughout his career.”

The exhibition moves through four major series from the 1970s: the Venetians, the Hoarfrosts, the Jammers, and a selection of stage collaborations. While visually distinct, the works trace a shared trajectory, one that mirrors the artist’s own, away from the din of Manhattan streets and into the shifting breezes of Captiva, Florida.

1 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg, Glacier (Hoarfrost), 1974. Solvent transfer on fabric with pillow, 120 × 74 × 5 7/8 in. (304.8 × 188 × 14.9 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Photo: Caroline Philippone.

2 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg, Bucket (Hoarfrost), 1974. Solvent transfer on fabric with fabric, 98 1/4 × 90 5/8 × 5 7/8 in. (249.6 × 230.2 × 14.9 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Photo: Ron Amstut.

3 ⁄8

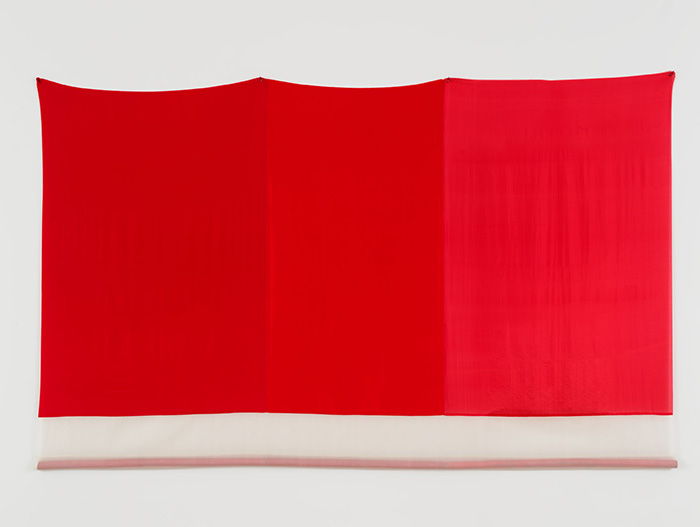

Robert Rauschenberg, Mirage (Jammer), 1975. Sewn fabric, 82 1/2 × 70 1/8 in. (209.6 × 178.1 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

4 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg, Sybil (Hoarfrost), 1974, from the series Hoarfrost. Solvent transfer on fabric, plastic and paper bag collage with rope, 82 × 82 1/2 in. (208.3 × 209.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of The American Contemporary Art Foundation, Inc., Leonard A. Lauder, President, by exchange 2014.300. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Photo: Courtesy the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

5 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg, Pimiento III (Jammer), 1976. Sewn fabric and cloth-covered rattan poles, 78 x 126 inches (198.1 x 320 cm). Private Collection, Courtesy of Gagosian. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy of Gagosian.

6 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg, Sant’Agnese (Venetian), 1973. Mosquito net, wood chairs, shoelaces, and corked glass jugs, 32 1/4 × 105 3/4 × 22 1/8 in. (81.9 × 268.6 × 56.2 cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Photo: Ron Amstutz.

7 ⁄8

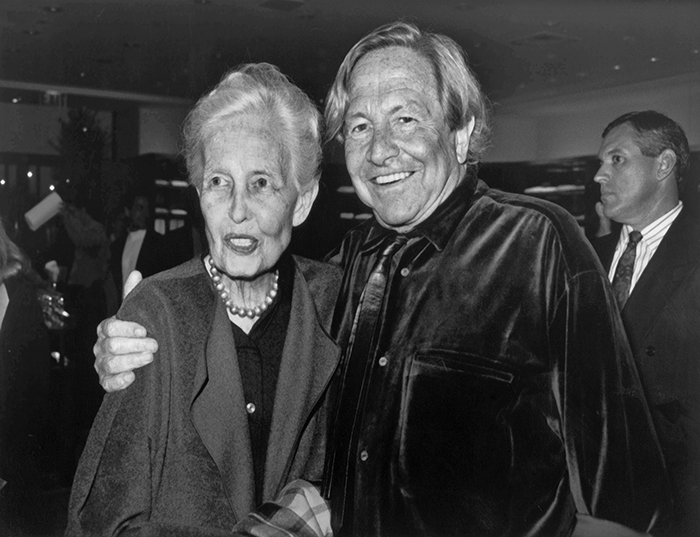

Dominique de Menil and Robert Rauschenberg, Houston, 1991. Courtesy of Menil Archives, The Menil Collection, Houston. Photo: Annie Amante.

8 ⁄8

Robert Rauschenberg; Dennis Hopper; Dickie Landry at the June 3, 1987, Menil Collection Inaugural Dinner. Photo: Crossley & Pogue.

White points to this transition as key, not just in geography, but in the material logic of his work. “He kept his residence in Manhattan but spent much more time on the Gulf Coast,” she said. “He had more exposure to the ocean breeze, started windsurfing. There’s a lot to the fabric works that speak to a nautical theme.”

The Jammers series makes this shift especially vivid. Tall, sail-like panels stretch toward the ceiling, sometimes tethered by wooden dowels, sometimes free to drift slightly with the air. They reference nautical forms, but they are not diagrams; they are encounters.

Hoarfrosts, on the other hand, are lighter still. Rauschenberg ran delicate fabric through his printing press, capturing newsprint images and ghostly transfers. Some hang limp, others billow. In their shimmer and fragility, they ask: what is left when the ink fades? What remains when memory grows transparent?

The show’s structure lets these bodies of work speak to each other, not as isolated experiments but as points along a shared arc. The Venetians, made from fabric stretched and hung over frames, take cues from both classical statuary and shopfront awnings. The later stage collaborations, including original sets and costumes for Merce Cunningham’s Travelogue, bring fabric into motion through bodies, choreography, and performance.

In these moments, Rauschenberg’s early training at Black Mountain College resurfaces. The fabric is not just a visual element; it becomes spatial, theatrical, even relational. There is also a glimpse of a younger Rauschenberg, before New York and art-world acclaim, corresponding with his childhood friend Arthur Frakes, sketching gowns, dreaming in seams.

“We have these incredible fashion design portfolios from his youth of gowns he designed and drew,” White shared. “It’s been a really fascinating aspect, and we question why it’s been suppressed within scholarship, and we’re pulling out those connections with this show.”

Rauschenberg’s use of fabric also opens up questions ignored by traditional art history. Why were these works, so rich, so meticulous in their own quiet way, dismissed at the time? Why did softness disqualify seriousness?

The answers are layered. Fabric has long been coded as domestic, feminine, and craft-oriented, categories often sidelined in the canon. Rauschenberg, who worked fluidly across boundaries of media and method, seemed less concerned with the labels than the potential. His fabric works, in their resistance to fixity, offer a form of rebellion, gentle but insistent.

As White plans the exhibition design, she intends to draw upon the connections between these bodies of work and highlight the throughline of the experimentation.

“In the exhibition, I really want to pull out the dialogue between them,” she shared. “You can start to see the great points of connection between them. For me, that’s really about his love of fabric and his experimental approach.”

In viewing these overlooked works, the Menil Collection offers the sense that Rauschenberg was not just experimenting with form, but asking something quietly radical: What if impermanence is not failure? What if softness is not weakness?

The Menil Collection has long had a relationship with Rauschenberg, dating back to the de Menil family’s early support of his career. This exhibition honors that connection while also unsettling expectations.

“I believe that spaces in between are important,” White said. “As a museum curator in this present moment, I hope any exhibition of important works of art can allow us to see things differently. I feel strongly that works that bring you to a place to experience something in the world, in real life, and allow you to challenge your assumptions is everything to our current moment.”

It is fitting, then, that this show arrives at a moment when many are reconsidering materiality, labor, gender, and the line between personal and political expression, and maybe something more: a question posed in cloth, caught in motion, never still.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN