The Dallas Opera’s production of The Flying Dutchman, beautifully conducted by Emmanuel Villaume and under the direction of chorus master Alexander Rom and stage director Christopher Alden, takes 1930s-era Germany as its visual and conceptual stage.

With curtain drawn, the overture is accompanied by an image of the cursed mariner (reproducing a self-portrait of German Expressionist Erich Heckel). The psychological agony of his curse is matched by the woodcut’s drama, and the scene is set for the unfolding story of the Dutchman’s search for redemptive love. It’s a story we know: cursed by Satan, the undead Dutchman can only be saved from eternal roaming by the love of a faithful woman, in this case embodied by Senta, who has spent her life pining after the mythic, tortured seaman.

As the curtain lifts, the male chorus, in regimented rows of sailors, embodies the best of Wagnerian spectacle. Indeed, both male and female choruses were exceptionally rich, heightening the emotional drama in fantastically bold performances that never lost their musicality to bombast. When the two choruses join in the third act for a night of drunken celebration, the combination is terrifyingly ecstatic.

Allen Moyer’s set is an off-kilter box, a massive open space walled with blue-gray wood panels that make a watery backdrop for the opera’s ship scenes and a disorienting, off-balance world when on land. A large wheel doubles as the ship’s helm and, in Senta’s later scenes, as a spinning wheel at a textile factory. It’s a brilliant decision, making a seemingly simple set beautifully versatile, and visually underscoring the emotional imbalances of the primary characters and the worlds they inhabit.

Underneath the tilted floor of the ship is a triangular underworld, made of pillars and beams to suggest the claustrophobic and hellish underbelly of the mariner’s ship. Used to impressive effect, this space is populated by ghosts doomed to sail with the Dutchman. In Dallas’s version, these figures are imagined as concentration camp victims, their shaved heads and dark eyes paired with prisoner’s striped clothing.

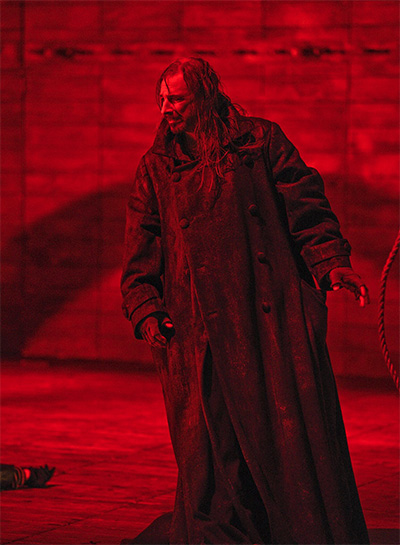

Both spaces of the set were transformed by Anne Militello’s on-point lighting design: from blood-reds and bright whites, to an almost black-light effect with purples and nauseous neon greens in the final party, color was a central protagonist in the emotional unfolding of the story.

Greer Grimsley’s rich bass-baritone gave his performance both power and pathos, his towering figure an impressively haunting presence, even when his gestures were understated. His heavy gray coat stretched out below him to form a massive pyramidal form, almost a character in and of itself. The heart of Grimsley’s performance, for me, was the moment in which he encounters Senta for the first time. Overwhelmed by emotion, he is also unable to meet her gaze, hiding his face against an open door through which he has just passed. The impact of that quietness, especially in contrast to his remarkable voice, underscored the brilliant subtlety of his performance.

Anja Kampe as Senta plays a woman obsessed and doomed, her clear soprano growing in fullness as her character steps from vulnerability to a confident embrace of this mysterious love-match.

Of course, nothing works out as it should.

Local huntsman Erik—Jay Hunter Morris, whose Texas-born tenor was the perfect earthy counterpoint to Grimsley’s Dutchman—enamored of Senta, proclaims his love for her. The mariner overhears them and spooks, believing Senta to be unfaithful after all. He abandons her, returning to the sea. In a twist on Wagner’s original, in which Senta drowns herself in despair, here, Erik shoots her dead.

We are meant to see Senta’s epic sacrifice for love as a kind of preordained tragedy leading to the Dutchman’s salvation, but I can’t help feeling exhausted by the decision to murder the lead female character. It’s a plot change that is entirely too predictable and painful, removing Senta’s agency at the one moment that Wagner allows her to have it. Indeed, in this surprise ending, an otherwise poignant production hits an especially wrong note.

By staging the Dutchman in 30s-era Germany, this production makes fascinating visual and conceptual propositions to complement Wagner’s compositional decisions and musical leitmotifs. Visually, those decisions are compelling and evocative. Conceptually, the historical context becomes muddy. If we are meant to take a lesson here, perhaps there is something about the potential of radical love, the welcoming of refugees accursed by the grim world around us… or perhaps it’s a gloomy reminder of the inevitability of disastrous violence.

—LAURA AUGUST