When an artist allows it, their practice can become all-encompassing, blurring the lines between practice, spirit, and the world around them. Beauty is found in the everyday: the preparation of a meal, a mother reading to her child on a porch, a bird lifting from a branch.

In a 1975 issue of Ceramics Monthly, she wrote, “You are not an artist simply because you paint or sculpt or make pots that cannot be used. An artist is a poet in his or her own medium. And when an artist produces a good piece, that work has mystery, an unsaid quality; it is alive.”

Toshiko Takaezu: Worlds Within is an ambitious traveling retrospective of the artist’s work, on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston from March 2-May 18, 2025.

“The exhibition is not only a look at her ceramics but the entirety of her practice: fiber, painting, bronze casting, and work on paper,” Essner explained. “It became an investigation of those who knew her work and a revelation for younger generations who do not know it.

At Takaezu’s death in 2011, the artist was revered by ceramicists but remained relatively unknown to anyone outside that sphere. Her work languished between the zones of craft and visual art, a margin in which many women thrived as men cast a looming shadow over paint and sculpture.

In 2023, Takaezu’s career took center stage with several exhibitions to celebrate the innovative nature of her artistic practice, including Shaping Abstraction at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Takaezu & Tawney: An Artist is a Poet at Crystal Bridges Museum in Bentonville, Arkansas.

1 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu, Purple Moon, c. 1998, stoneware, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Leatrice S. and Melvin B. Eagle Collection, gift of Leatrice and Melvin Eagle, 2010.2265. © Family of Toshiko Takaez.

2 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu, Closed Form, 2004, porcelain, private collection. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photo: Nicholas Knight, courtesy The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

3 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu, Gaea (Earth Mother), 1979, stoneware and hammocks, Racine Art Museum, gift of the artist; Exploded Moon, 1972, stoneware, collection of Linda Leonard Schlenger. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photo: Nicholas Knight, courtesy The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

4 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu, works from the Star Series, c. 1994– 2001, stoneware, Racine Art Museum, gift of the artist; Early Spring, c. 2000, stoneware, Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, gift of the artist in honor of Gerhardt Knodel, CAM 2007.24; Cherry Blossom, 1997, stoneware, private collection. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photo: Nicholas Knight, courtesy The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

5 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu, Double-Spouted Vase, c. 1957, stoneware, Pier S. Voulkos and Daniel R. Peters Trust. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photo: Nicholas Knight, courtesy The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum.

6/7

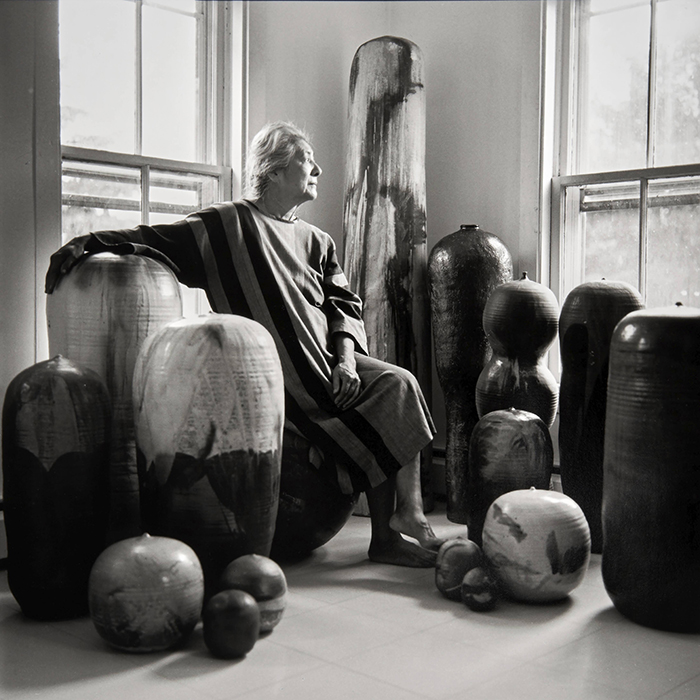

Bobby Jae Kim, Toshiko Takaezu with her works at home in Quakertown, New Jersey, 1977, gelatin silver print, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Liliane and David M. Stewart Collection, gift of Bobby Jae Kim, D97.183.1. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu.

7 ⁄7

Toshiko Takaezu with works later combined in the Star Series (c. 1994–2001), including (from left to right) Sahu, Nommo, Emme Ya, Unas, and Po Tolo (Dark Companion), 1998. © Family of Toshiko Takaezu. Photo: Tom Grotta, courtesy of browngrotta arts.

Worlds Within pulls its title from Takaezu’s own description of a universe within a pot; specifically, the closed forms that became a critical part of her practice. With the form completely sealed, Takaezu fostered a sense of mystery in her pieces, often claiming to have written messages on the inside or included writings on paper that would burn in the process.

“She thought about it as a dark space that we cannot see,” Essner explained. “The idea of interiority related to these cosmic, metaphysical ideas invisible to us, and over the course of her career it became a means of exploration.”

In this vein, co-curator Glenn Adamson posed the idea that you can see her work as single pieces but also in these installations and as a lifetime of achievement, each piece relating to the one prior and the one after.

For Essner and the museum, the installation process and the structure of the exhibition are a means to encapsulate and translate the aura and history of Takaezu.

“Installation is really essential to understanding this exhibition,” she said. “We will have black sand as a central component of displaying her work, referential to her life in Hawaii, but we also looked to her own approach to installing her works and installations to develop re-creations that honor her vision.”

Takaezu’s closed forms became 360-degree canvases for expression in glaze, offering the artist a deeper means of exploration that she continued to refine throughout her life. She closed the shapes to take the practical use out of her works, leaving a small, spout-like pinch at one end. These vessels would become cocoons, snails, and pods, some of which fit in the palm of your hand while others, like the Star Series, were over 7 feet tall.

In a 2003 interview with Gerry Williams for the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian, Takaezu described the process of creating these giant forms as “very slow but it’s moving, and I felt all this beckoning to drop into the pot.” When Williams asked whether she felt she herself would drop into the pot, she responded, “Yes, I wanted to go in the pot itself. You can feel the pounding of your heart. It was beating, because it’s a frightening experience that, you know, you want to move with the form going, and then, you know, you get dizzy, you want to go in.”

For those familiar with her work, the exhibition is an opportunity to gain a new understanding of its impact. “For those that do not know her work,” Essner mused, “I think they’ll find it revelatory. The meaning, vitality, beauty, and the multisensory relationship one can have with her work is something I am so looking forward to bringing to Houston audiences.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN