When did you first learn that art had power? For groundbreaking Chicana artist, activist, scholar, and educator Amalia Mesa-Bains, the revelation came to her as a child.

The artist recounts this memory in a short video from the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive who, in collaboration with the Latinx Research Center (LRC) at UC Berkeley, organized the nationally touring exhibition Amalia Mesa-Bains: Archaeology of Memory, on view at San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) from Sept. 20, 2024 to Jan. 12, 2025. The show celebrates Mesa-Bains’s more than forty-five years of artistic practice. Unique to SAMA’s iteration is the debut of her new, large-scale sculpture Cihuatlampa, which “explores the celestial space of the Mexica (Aztec) afterlife of women who died in childbirth.”

“When I came into the Chicano movement in the early 1970s, there was no expectation that anyone else would want to see our work. We did our work for our own community, to build our own organizations. We really created our own venues,” she says.

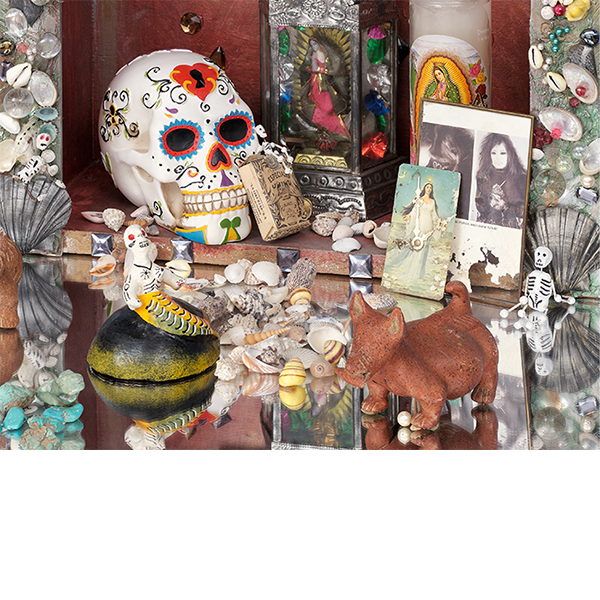

Archaeology of Memory includes a range of media, featuring forty works created between 1991 and 2024. For example, Queen of the Waters, Mother of the Land of theDead: Homenaje a Tonatzin/Guadalupe (1992) is a two-tiered mirrored altar with a plethora of found objects, surrounded by dried flowers, dried pomegranate, and potpourri on the floor, with jeweled clocks under a satin fabric drape on the wall. The autobiographical Venus Envy Chapter I: First Holy Communion, Moments Before the End (1993/2022) presents a fabric-skirted chair and white vanity dresser, the surface of which is covered with feathers, pearls, photographs, and a myriad of personal and devotional objects.

1 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: What the River Gave to Me, 2002; mixed media installation including hand-carved and painted sculptural landscape, LED lighting, crushed glass, hand-blown and engraved glass rocks, candles; 48 x 48 x 168 in.; courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: John Janca.

2 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Circle of Ancestors, 1995; mixed media installation including candles and seven hand-painted chairs with mirrors and jewels; 168 in. diameter; courtesy of the artist and the Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

3 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Queen of the Waters, Mother of the Land of the Dead: Homenaje a Tonatzin/Guadalupe, 1992 (detail); mixed media installation including fabric drape, six jeweled clocks, mirror pedestals with grottos, nicho box, found objects, dried flowers, dried pomegranate, potpourri; 120 x 216 x 72 in.;courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

4 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Venus Envy II: The Virgin’s Garden, 1994 (detail); mixed media installation; 180 x 120 x 72 in.; courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

5 ⁄8

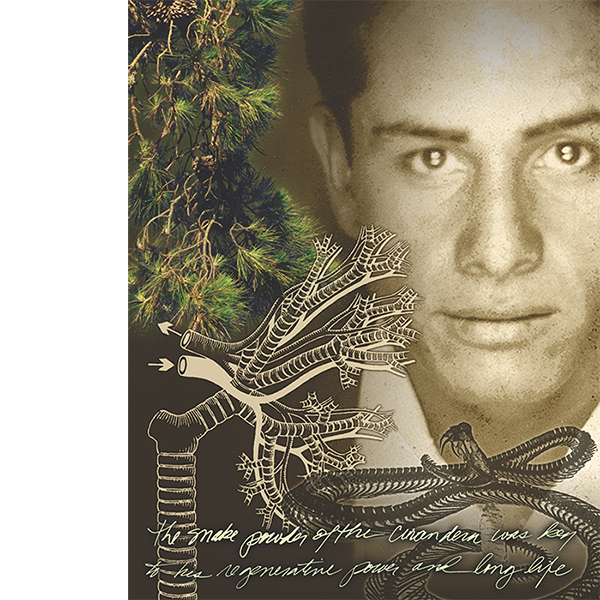

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Curando in Venus Envy Chapter IV: The Road to Paris and Its Aftermath, The Curandera’s Botanica, 2008/2023; Giclee print; 36 x 24 in.; courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

6 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Guadalupe Twins in Venus Envy, Chapter III: Cihuatlampa, 1997; Giclee print; 14 x 36 in.; courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

7 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Queen of the Waters, Mother of the Land of the Dead: Homenaje a Tonantzin/Guadalupe, 1992. Photo: Daria Lugina.

8 ⁄8

Amalia Mesa-Bains: Queen of the Waters, Mother of the Land of the Dead: Homenaje a Tonatzin/Guadalupe, 1992; mixed media installation including fabric drape, six jeweled clocks, mirror pedestals with grottos, nicho box, found objects, dried flowers, dried pomegranate, potpourri; 120 x 216 x 72 in.; courtesy of the artist and Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco.

“I realize that I persisted in making the work because it was my salvation,” she says. “It was the way I would heal myself, and I couldn’t stop working. My mother and father died during that time, and then my brother died. So, throughout the show is grief, healing, and loss.” She also suffered the death of her younger sister, Judith, who ran her studio for years.

Mesa-Bains has taken note of people’s responses to the show, including those who are not in her community.

“When I would go to take pieces down after a show, I saw that people had slipped in notes, copies of green cards, folding cards from funerals—things would appear that I knew I’d never put in there,” she says. “That’s when I realized: Even though it’s not the same, and even though these may be different communities, they’re still having some sort of a ceremonial relationship with it.”

The artist reflects, “It was a fortuitous time with the right people in the right places, and I’m very glad for it.”

It seems as though the line that Mesa-Bains has drawn extends beyond the paper. Whether it’s her revolutionary altar-installations or mutually supportive relationships with Latina curators—or any number of conversations, writings, and other offerings—she has used art’s power for good, saying, “In some ways I feel that I’m opening the door for some of the other artists of my generation.”

—NANCY ZASTUDIL