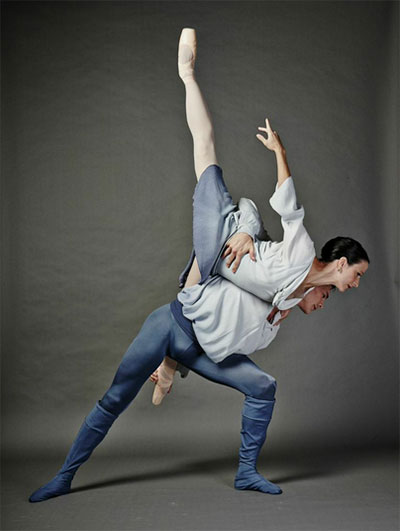

Leticia Oliveira and Carl Coomer in Texas Ballet Theater’s production of Jiří Kylián’s Petite Mort. Photo by Steven Visneau.

Dancers float like drifting clouds at the start of Five Poems, looking as if they were walking in the sky. The choreographic motif returns over the course of Ben Stevenson’s abstract ballet, lifted by Wagner’s yearning Wesendonck Songs and Jane Seymour’s ethereal set design—yes, that Jane Seymour. Created toward the end of his long stint as artistic director of Houston Ballet, it’s one of Stevenson’s most gorgeous works.

His current company, Fort Worth-based Texas Ballet Theater, revives Five Poems at Dallas City Performance Hall on April 17-19 as part of its “Masterworks” program, along with the Balanchine warhorse Rubies and Petite Mort, the troupe’s first crack at a Jiří Kylián piece. Then on May 29-31, Five Poems is replaced on the similar “Artistic Director’s Choice” bill at Bass Performance Hall by the world premiere of a commissioned work by Jonathan Watkins, a former dancer with the Royal Ballet.

“I was always crazy about the music, and when you decide to make a ballet you often fall back on music you love,” Stevenson says of Wagner’s score for Five Poems, which is set to poems written by his lover. “It’s very melodic. It soars and takes you with it.”

Stevenson accidentally discovered that he had taught dance to actress Jane Seymour in London when she was 13 and still using her given name, Joyce Frankenberg. Later, he recognized her when she was performing in a play, and they became friends. Five Poems was her first design for dance, but it was influential on Stevenson. Paintings of clouds he saw in her studio helped inspire the choreography. The huge backdrop is a watercolor cloudscape by Seymour. The dancers wear delicate, translucent costumes that she also designed.

“She was nervous, but agreed to do it,” Stevenson says. “I thought of the choreography as walking in clouds. The dancers sort of walk over one another, fly over one another as if they are literally walking in the sky.” During the fourth poem, a single female dancer performs somersaults while being held aloft by three men. Her feet never touch the ground. It’s breathtaking.

He hopes audiences will be as moved by Petite Mort as he attempts to balance Texas Ballet Theater shows with more contemporary work by younger choreographers. “The title means the little death, and it’s quite sexual in a way. The movement really is thrilling,” he says. “The way he moves dancers and his invention are wonderful. He’s one of my personal favorite choreographers. It’s about balance. All the pieces are very different. There’s me, who’s just about still living, and there’s Balanchine, who sadly isn’t, but is a very famous father of American ballet. And then there’s Jiří Kylián, who’s probably the master working today.”

The commission from Watkins, who at 16 won the Kenneth MacMillan Choreography Award, is another balancing act. Stevenson describes the British choreographer’s style as neo-classical, but didn’t know yet what the piece will look like or what it’s going to be called. Watkins had not started setting it on the dancers. He has tapped two Texans to help him: Austin-based costume designer Kari Perkins and Dallas composer Ryan Cockerham. “He’s done some successful pieces,” Stevenson says of Watkins. “I was trying to get a few world premieres in the company, so I approached him. He moves dancers very well.”

Stevenson plans to commission at least one company or world premiere each season. He says it’s an important step in keeping the dancers sharp and growing the Texas Ballet Theater audience. “I’m very anxious to do new works, to get more world premieres. I think that gives the company its face. I’m forging ahead and trying to make our programming as exciting as possible and to inspire our dancers to go higher and higher.”

The new work will mostly come from other choreographers. “I did so much when I first came here,” Stevenson says. “We didn’t have enough money to spend, so I gave a lot of my ballets to the company. Now I want to bring in choreographers I haven’t had the chance to do before. It’s important to the dancers’ development and to the audience, so it’s not just the Ben Stevenson dance company.”

—MANUEL MENDOZA