A group of fish tanks sit at varying heights before a white wall—some on the ground, others atop milk crates. Light shines from within and upon each tank, the gridded shadows evoking an illusion of form and color as though painted onto the wall.

Donnett’s practice is inquisitive, a teasing apart of concepts and ideas into threads to be woven and regenerated into a new context. Within the fish tanks of City of Atlantis: I’ll Always Come Back to You, 2025, water and a mixture of Indigo ink, dyes, and Kool-Aid blend to add color and texture to the piece, a repurposing of materials meaningful in different ways to different environments, additional threads reaching beyond the piece and into the ether.

“What tools created those shadows? Was it the transparency in the glass, reflections in the room, the light bending? These are the same questions you ask about a painting,” he continued. “Some of these materials and processes, considered necessary to create a painting are removed from the wall, which can be a painting, sculpture, or installation. In some tanks, there are objects. Is the object in the tank like an object in the painting?”

His work ranges from two-dimensional pieces to large-scale installations that envelop the audience and offer connections that reach outside the walls of the museum, whether those of the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Project Row Houses, the Visual Arts Center, or the University Museum at Texas Southern University.

Donnett returned to Houston following the completion of his MFA at Yale University and such prestigious fellowships as the John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship and the American Academy of Rome Affiliated Fellowship. Currently, Donnett is a scholar in residence with the University of Houston Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts.

In conversation, Donnett spoke about initially feeling like an outsider to the art world and the world at large, instilling an interest in establishing connections in his work, between the viewer, the world, and ideas.

“I want to offer familiarity through materials and subject,” he said, reflecting on the multifaceted notions of community in his practice. “In my work, one perspective of community is how the material and personal relationships I develop with the public. These substantive relationships offer up a set of inquiries and conditions that I like to explore.”

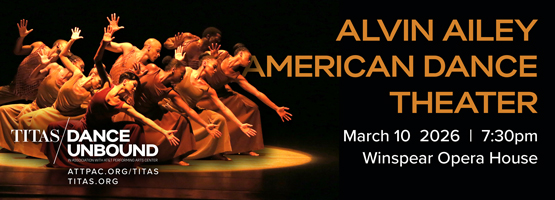

1 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Intimate Exchange of Open Enclosures. Found and reclaimed window screens, silk screen t-shirts, African sculpture tambourine jingles, stereo speaker, books, aluminum foil, record albums. Size varies depending on the exhibition space 2022. Photo by Rick Wells.

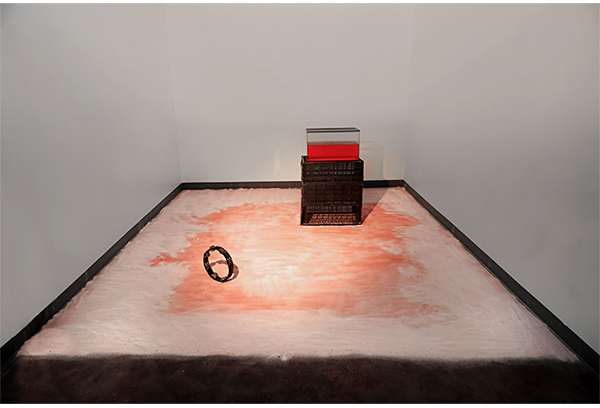

2 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Flowbodyegoplasmadefshift 9191. Milk crates, fish tank, water, Kool-Aid, tambourine, tambourine jingles record albums, light, shadows on walls. Size varies depending on the exhibition space 2024. Photo by Rick Wells.

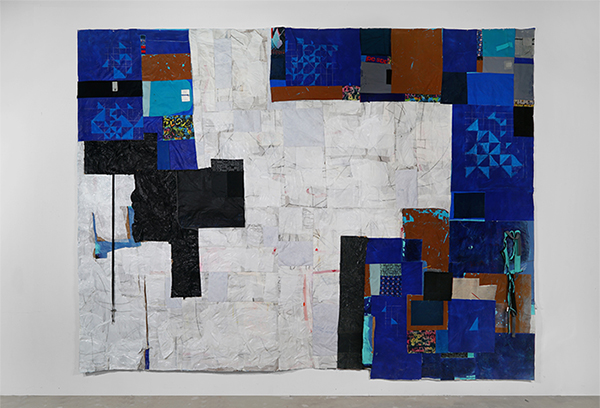

3 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Nebula. Reclaimed backpacks, duct tape, plastic trash bags, tambourine jingles, shoelace ink, Chinese marker, aerosol paint, house paint, acrylic paint, graphite, fabric thread, paper. 121” x 157” 2023. Photo by Rick Wells.

4 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Monolith Transmitter Starlight Station. Reclaimed school desks, duct tape, frames, tambourine jingles, 2022. Photo by Rick Wells.

5 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Black Ocean of Eternal Soulameens. Bought, donated, and reclaimed earring studs, house paint lights, 50’ x 12’ wall, 2024. Photo by Rick Wells.

6 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Before Aftertime 1 (Rome Series). Reclaimed paper, cement, fabric, plastic trash bags, duct tape, ink, house paint, aerosol paint, 34” x 23,” 2024. Photo by Rick Wells.

7 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Spatial Coding Antenna. Wood, 44.5” x 48” x 54” 2023. Photo by Rick Wells.

8 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, Birth of the Universe II. Snare drum, radio/tv antennas, charcoal LED light, wood 2023. Photo by Rick Wells.

9 ⁄9

Nathaniel Donnett, City of Atlantis: I’ll Always Come Back to You. Milk crates, fish tanks, Indigo dyes, water, African sculptures, aluminum foil, fabrics, books, bottles, tambourine jingles, filters, foot pedals, speakers, sound, lights, shadows on walls. Size varies depending on the exhibition space, 2025. Photo by Rick Wells.

“A community is constantly in flux and musical based on specific patterns,” he explained. “I try to mimic this in my practice, but it also exists in solitude and absent from community. I move between both spaces. I come from that which I make work from.”

In Acknowledgment: The Historic Polyrhythm of Being(s), 2022, he installed a series of backpacks on the fence surrounding a CAMH undergoing renovations. Sourcing the backpacks via an exchange for students returning to school Donnett considered them as a means of transferring and transporting education, blue lights interacting with the materials to create a painting while their practical counterparts tied threads to communities that may view museums as exclusionary.

Donnett sums up the core of his practice as “Dark Imaginarence,” a two-fold, fluctuating yin-yang sometimes in balance but genuinely in harmony. When he speaks on this concept, he breaks it down into its two counterparts: darkness and a blend of imagination and experience.

While Donnett has a history of using deep hues within his work, the darkness at play is less literal—the poetics and asymmetry of the world, the unknown and the uncertain.

The result, Donnett surmises, is that blackness blooms within enclosures, projecting material imagination as a survival mechanism onto the world. It is single and whole yet incomplete, malleable, moving beyond a single definition—a poetry of its own being.

On the other side of his practice, Imaginarence encapsulates both the mental and physical aspects of the work.

“Imagination and experience are necessary for most forms of communication and humanity to exist, worlds to build, or unknown territories to discover,” Donnett said, speaking on imagination as a necessity to move beyond limitations and restrictions placed by society or the self. “Therefore, I try to implement it by creating spaces and works that move in many directions.”

Without imagination, someone who may attempt to engage with the work may experience nothing at all. However, we gain physical experience in what we know, what is familiar to us, pulling Donnett towards material and aural choices in his work that foster this sense of familiarity.

When Donnett speaks of engagement with his work, he hopes for viewers to feel the curiosity and inquisitiveness that drive him.

“Ideally, I’d like them to apply their ideas, questions, or conclusions about the work,” he said. “That is when the imagination and experience come together, creating a question that happens to be the dark(ness) in the work.”

—MICHAEL McFADDEN