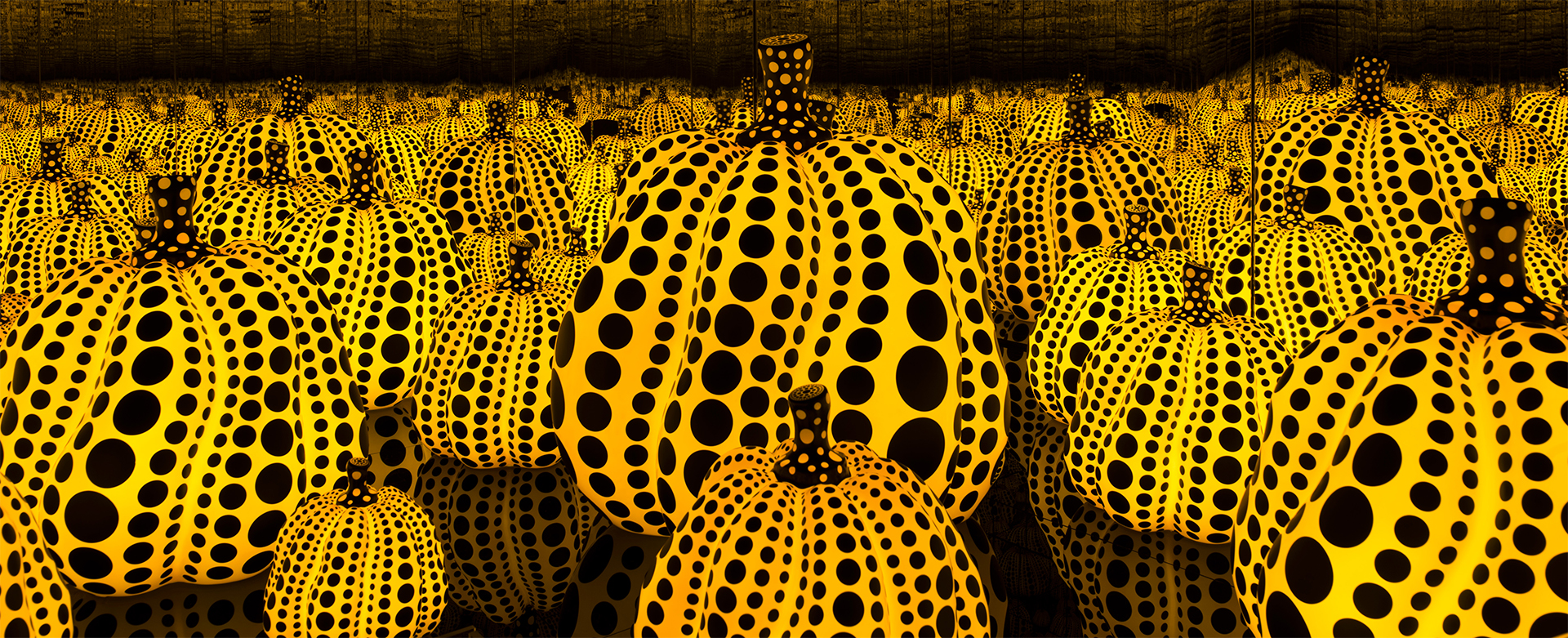

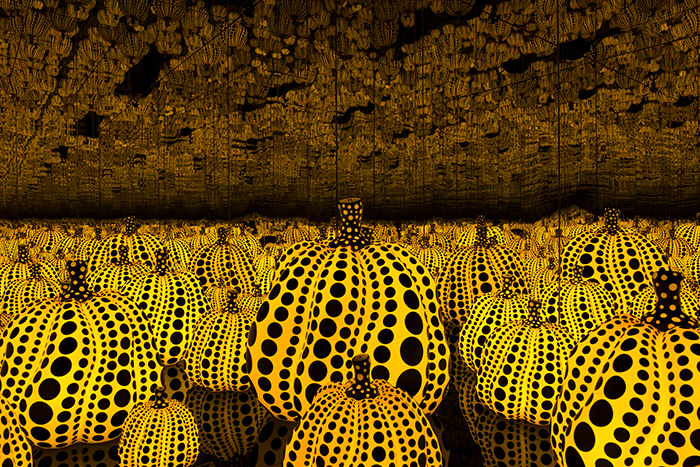

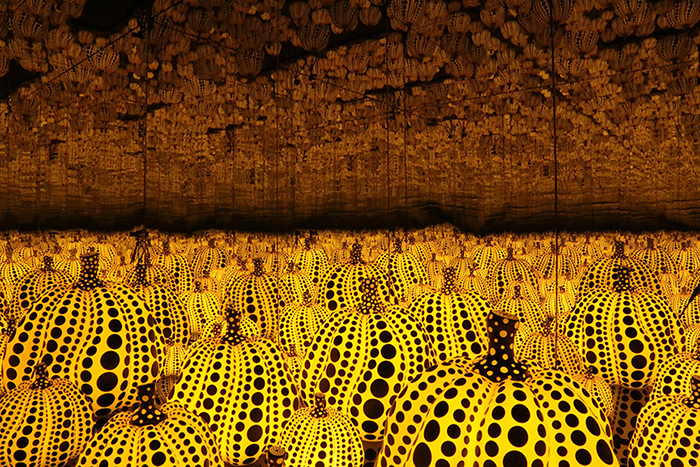

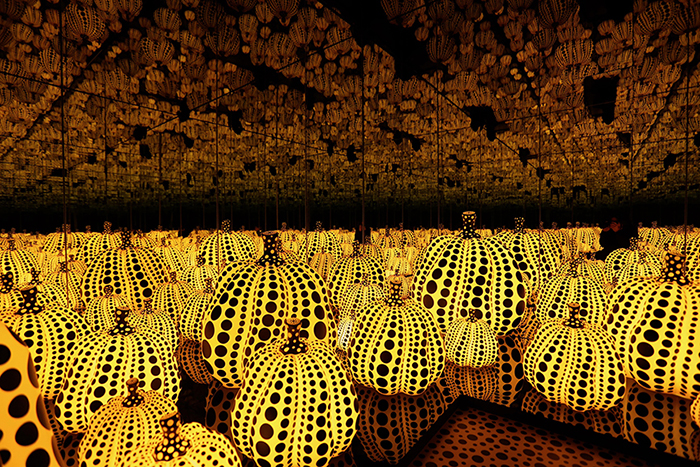

It begins with the silent closure of a mirrored door. Suddenly, you are enveloped in a shimmering chamber filled with what seems to be an infinite patch of polka-dotted pumpkins, a bumper crop designed to immerse and enchant.

Yet, these seemingly whimsical pumpkins represent so much more for Kusama herself. One of the artist’s most quintessential symbols, the humble gourds were the earliest images to fire up her imagination. Raised in Matsumoto by a family of merchants who owned a seed farm and nursery, Kusama began drawing pictures of pumpkins in elementary school.

“The pumpkin and the dots are so ubiquitous and identified with Kusama, but they go back to how she grew up on a farm,” says Vivian Li, the museum’s Lupe Murchison Curator of Contemporary Art. “Her father was a wealthy businessman who was running a large seed nursery that distributed all over Japan. So, as she was growing up in the countryside, she was using the pumpkin as a continuous motif. She also had these hallucinations early on in her life and she was taken by its whimsical form. She had already started self-identifying with the pumpkin—to this day, she sees it as an avatar or a portrait of herself.”

By the early 1960s, the artist had shifted into building her mirrored infinity rooms and creating happenings involving nude performers painted in polka dots. But it wasn’t until she participated in the Venice Biennale in 1966 with a guerrilla staging of 1500 mirrored spheres outside the Italian pavilion that Kusama’s work entered the canon of art history.

Feeling rejected by the art world, Kusama returned to Japan in 1974 and began her practice all over again from the ground up. She returned to the symbolism of the pumpkins as she explored other methodologies, including printmaking, collage, and writing. From her room at Seiwa Hospital (where she still resides), she rebuilt her life, returning once again to a symbol that meant so much from her earliest days.

“She wasn’t finding the recognition she wanted,” explains Li. “People put her in different boxes as a female artist, an Asian artist, a Japanese artist. So, she moved back to Tokyo and started over again. She also rediscovered the pumpkin, and that became a prime motif for her. By the early ’80s, it was incorporated in her art patterning and vocabulary.”

1 ⁄3

Yayoi Kusama, All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016, wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, and LED, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2018.12.A–I. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

2 ⁄3

Yayoi Kusama, All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016, wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, and LED, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2018.12.A–I. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

3 ⁄3

Yayoi Kusama, All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins, 2016, wood, mirror, plastic, acrylic, and LED, Dallas Museum of Art, TWO x TWO for AIDS and Art Fund, 2018.12.A–I. © YAYOI KUSAMA. Courtesy Ota Fine Arts, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

It’s shocking that she finally became a darling of the art world so late in life, yet perhaps Kusama’s dynamic details—the dots, the mirrors, the pumpkins—just needed to align with a time when viewers were ready to understand their meanings. Both visionary and tenacious, she never gave up until her audience was ready to immerse themselves in her work.

“It was just from a couple of prescient, smart curators that got her invited to represent Japan in 1993,” says Li. “She’s such a visionary artist for our time in so many ways, and her vision has always been there, but there hasn’t been recognition at different points in her life.”

The Dallas Museum of Art initially acquired All the Eternal Love I Have for the Pumpkins in 2017 (the year after it was created), putting it on view shortly afterwards. As many new residents who might not know the DMA owns a Kusama have relocated to the city, it made sense to reinstall the piece with a few more guardrails in place.

This time, a guard stands in the room to ensure the sculptures experience the minimum amount of wear and tear. Visitors are required to put their phones in a lanyard to avoid accidental spills. Handbags are banned, and the DMA offers a specific “know as you go” list to cover any eventuality when viewing Kusama’s piece.

Now 96, Kusama is still working daily in her studio on art, knowing she’ll leave Earth with pieces like this infinity room serving as a repository of hope, particularly for young artists who can benefit from her persistence in establishing her art and vision.

Li adds, “She wanted people to feel they could get lost in infinity and also be connected to each other and to the nature of the world. That’s what saved her. In her poetry, she talks about this often: to lose yourself and be connected with the beauty of the universe—that is what has sustained her and her art over all these decades. She hopes her work will continue to bring the same sense of joy and connection to people.”

—KENDALL MORGAN