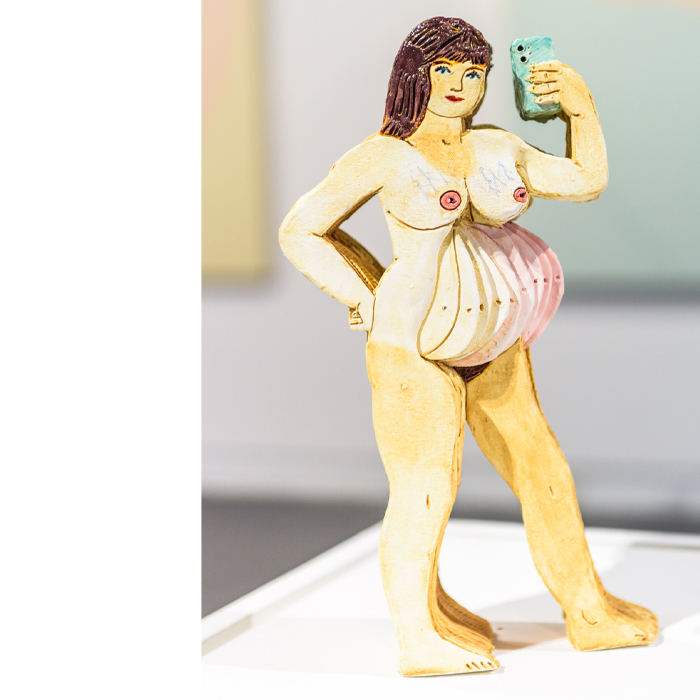

Surprise, delight, and discomfort are a few of the feelings you may experience upon entering Designing Motherhood, an ambitious, wide-ranging, but ultimately cohesive survey of the physical, psychological, and political experience of human reproduction. On view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft through March 15, 2025, and organized by HCCC Curator and Exhibitions Director Sarah Darro, Designing Motherhood presents the science and strangeness of conception, birth, and childcare, as viewed through the prism of craft, design, and fine art. With over 60 objects spanning the past 50 years on display, including 10 works by Texas-based artists, there’s a lot to look at and some of it ain’t for the squeamish. But art, when it’s connecting you to what it means to be alive, isn’t always comfortable. “I consider all of these objects in the show art objects,” says Darro. “These objects hold a lot of power, and visitors are having very visceral reactions.”

The HCCC iteration is also the first to focus on craft, a discipline defined by its materials, process, and how technique is passed down to succeeding generations. “For me, care feels synonymous with craft,” says Darro. Indeed, the hand of the craftsperson is imbued in a caregiving object as straightforward as the Kuddle-Up Blanket, a baby blanket first produced in the 1950s. Meanwhile, the art in the show is installed in direct proximity to these functional objects to support the idea of caretaking and reproductive experiences as analogous to craft and other creative disciplines. “They require so much time, labor, and practice,” says Darro of art making. “It’s not inherent knowledge. It’s passed between generations.”

1 ⁄7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

2 ⁄7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

3⁄ 7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Featuring Alecia Eggert’s OURs, 2022-2024. In collaboration with Sarah Sandman and Planned Parenthood. Neon, custom controller, steel, paint. 20 x 48 x 120 inches. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

4 ⁄7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

5 ⁄7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Featuring Liss LaFleur’s and Katherine Sobering’s Queer Birth Project Collection 1: on bodies, 2022. Steel, neon tubes, electrical wire, transformer, and glass rods. 30” x 23” x 3” inches. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

6 ⁄7

Gallery view of “Designing Motherhood” at Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. Featuring Madeline Donahue’s Biological Clock, 2021. Glazed ceramic. 7 x 6 x 12 inches. Photo by Graham W. Bell.

7 ⁄7

Francesca Fuchs, Baby 1, 2004. Acrylic on canvas. 86 x 127 inches. Photo courtesy of the artist and Inman Gallery.

Throughout the exhibit, objects representing past eras of design, including a 70s-era Fisher-Price nursery monitor, a vintage glass Stork nursing bottle, and antiquated products created to aid with menstruation, fertility, and pregnancy, engage in an unspoken dialogue with such dramatic standalone works as Aimee Koran’s blood-red chrome-plated breast pump and Kim Harty’s blown and cut glass uterine sculptures. Other thoughtfully curated combinations of craft, design, and art objects address miscarriage, abortion access, and disaster preparedness for parents.

One of the many admirable things about Designing Motherhood is its commitment to promoting a deeper knowledge of the arc of human reproduction through the power of art. “Parenthood and motherhood is like any other skilled discipline,” says Darro. “It’s a mistake to think it’s an inherent knowledge we all carry inside.” In the last gallery of the exhibit, Liss LaFleur and Katherine Sobering’s neon and fringe installation, Queer Birth Project, glows like an empty disco, illuminating a space for visitors to sit with what they’ve seen, and consider the role caregiving plays in our existence as a communal species.

—CHRIS BECKER