Now a Painter, the Decider Still Plays By His Own Rules

This really is not the place to debate who is the best (or worst) painter, George W. Bush or David Bates. This is, however, just about the best place imaginable to question the location, logic, legitimacy, motivation, and quality of The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy, an exhibition including 30 portraits of world leaders by the 43rd President of the United States, George W. Bush, and sundry trinkets gifted personally by important internationals to the President.

Even as it attracted national attention and bemusement, the exhibition opened at 9 a.m. April 5 at the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum to little fanfare in the local art world. There was no public vernissage where art-fanboys might tip hats to a curator and the new artist on the scene, Dubya, while getting tipsy from champagne. That affair was held in secrecy several nights before, following patterns of opacity similar to those in which his administration was shrouded and which one similarly encounters in the attempt to reach a human voice on the phone at G.W.’s SMU-based institution. Keeping Dubya’s show opener under wraps likewise distanced him from the grubby hoi polloi who are the denizens of the indigenous art world, and any would-be detractors.

The shebang and wow so usual to the debut of an art exhibition, as research from experts, which also makes an artist’s body of work open to critical reception, was left to Centraltrak: The UT Dallas Artists Residency, where two G.W. impersonators showed up the night of April 5 at The Paintings of *George W. Bush, an exhibition that lampooned the show over at SMU.

Curated by young, hot spitfires Morehshin Allahyari and Julie McKendrick, The Paintings of *George W. Bush regaled the world with fake but faithful art: copies of George W. Bush paintings made by “Children of Artemis—Sketch Cult,” a regularly assembled group of Dallas artists at Centraltrak who make art in a communal setting. It was a short-lived but powerful foil to Dubya’s show at the SMU Museum, ponying up the critical evaluation from which our 43rd President has seemingly tried to duck. In mirroring the exhibition of paintings by the president, the Centraltrak show highlights the absurdity of a president who, considered by so many to be a thoughtless, trigger-happy war criminal, blithely takes up painting, the art of incremental rumination.

There was none of the usual art-world protocol for The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy, and that should serve to tip us off about the three L’s: Location, logic, and legitimacy. This is “art” of another stripe. Think here amateurish Sunday hobby painting or self-soothing from paint-by-numbers. And of course, one must not deny the glaring nepotism at work in an art exhibition of one’s own work in one’s self-proclaimed Valhalla. Louis XIV famously said, “L’état, c’est moi!” From monarchy to oligarchy, like Louis, G.W. Bush is autonomous, works within a world of few rules, and is still his own judge.

What is lost in terms of legitimacy is gained perversely in terms of the very same location, the architecture of the G.W. Bush Library and Museum. The monumental classicizing modernism of Robert A.M. Stern’s Freedom Hall has a corporate grandeur. Its rarefied volumes with an extruded grid functioning as a sun-break dig out the deep grammar of classicism within architecture writ large, just as did the massive colonnades of Albert Speer’s Zeppelinfeld (1933) in Nuremberg or any one of the buildings at E.U.R. (1942), Mussolini’s new town in suburban Rome. Like these buildings, the G.W. Bush Library and Museum is a peaceful oasis functioning inversely to the hawk-like policies propagated when he was in power. Signs and guards alike make it very clear upon entering Freedom Hall: Remove your weapons friends. No guns allowed!

Dubya lays bare the roots of his motivation in the seven-minute video produced by the History Channel that precedes the painting exhibition. There we see Dubya shyly explaining his turn toward painting in his post-presidency years. “I’ll be painting ’til I drop,” he says. The former President is intermittently encouraged along by his maternal-seeming wife at his side on the couch. The message here is that Dubya is a nice guy, a man not simply of diplomacy, but a regular person like all of us. Never mind that he originally fares from New England, not Texas or anywhere near the south, that there is a family dynasty and gobs of wealth. The short video shows a montage of clips: Dubya’s bona fide diplomacy with international leaders and a cut-away to Condoleeza Rice adulating Bush for his kindness further evidence of which can be found, she claims, in his painting.

Many political leaders in history were painters, such as Ulysses S. Grant, Adolf Hitler, and Dwight D. Eisenhower. The radix of Bush’s will-to-art is the heroic British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. At the suggestion of a friend, G. W. read Churchill’s Painting as A Pastime, published in 1965. Following this, G. W. started painting with oil in 2012 at the age of 65.

A comparison of the two men is useful here. Like Churchill, G.W. paints figures rather than abstractions. In a review of Churchill’s book, the eminent 20th-century art historian E.H. Gombrich wrote of the special-interest-jukebox that figural painting seems to be, noting that it is legible, accessible and a good place from which to launch as a painter-hobbyist. In Churchill’s time, painting figures—en plein air or in the studio—was the norm. What Gombrich said of Churchill applies in some certain sense to G.W. as well: “He [Churchill] was lucky to be born into a generation whose artistic idiom was more easily accessible to the amateur than was any previous style of painting.” Unlike Bush, Churchill took up painting when he was in his 40s, in the 1920s, and he exhibited his work in Paris under a pseudonym (Charles Morin). He sold five landscapes for thirty pounds each.

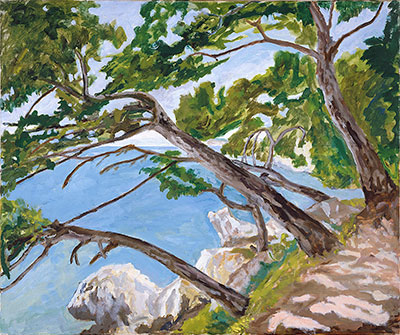

The two men also have unique ties to Dallas. G. W. resides here while likenesses and indices of Churchill do in the collection of the Dallas Museum of Art. One finds in the archives of the DMA photographs of Churchill painting at La Pausa, the French Riviera villa of Churchill’s close friends, Emery and Wendy Reves; Wendy was born in the East Texas town of Marshall. Equally haunting is the landscape painting by Churchill, hung within the on-site replica of La Pausa that is part of the permanent display of the Reves collection at the DMA. Churchill’s ambition to show and sell his work in Paris reveals a deeper understanding of making art as both a conceptual enterprise as well as part of a profound history that engages a public intelligentsia.

Nevertheless, G.W.’s portraits are not simply the failed stuff of poor craft and missed verisimilitude. He based his portraits of international leaders on a combination of photographs and memories. They are reminiscent of the intentionally naïve paintings of Belgian artist Luc Tuymans, whose work sells for high dollars while inflected with a related mystery of a lost Belgian empire about which Tuymans reminisced in a public talk at the DMA in 2010.

G.W.’s portrait of Tony Blair is probably the most carefully wrought, and this is likely because Blair was so amicable with the President. G. W. modeled Blair’s face in peachy tones with some aplomb. By contrast, G.W.’s self-portrait is messy and incomplete, as if to suggest an unusual streak of self-awareness, even existential self-deprecation. As amateur works, they also seem to be the result of sheer diligence and chance. The portrait of Angela Merkel is especially serendipitous. The Picasso-esque abstraction created by the asymmetry between her eyes (one is higher than the other) is less a matter of intention and more the accidental result of the limner painter that G.W. is. In an attempt to give volume to Merkel’s visage, G.W. seems to have forayed far from binaries into the unknown subjective territory of thinking abstractions.

Further heightening the sense that these paintings are more archival artifacts than art, the installation of the exhibition is cluttered and slipshod. The gifts from world leaders seem at times to supersede the paintings in importance.

But all this does not rule out the changes in a man that such a turn to art might suggest. And here I would like to end on the thematic of time and deliberative thought.

As if to separate the man from his presidency and post-presidency, as well as from partisan politics, the museum is split into two areas. The permanent museum exhibition gallery and temporary exhibition gallery sit astride the central 67-foot-tall Freedom Hall. Inside the former, there are several installations including the Decision Points Theater, which is arranged something like the United Nations in miniature. (Never mind that Republicans loathe the UN.) Several individual seats face touch screens that in turn are opposite a wall upon which is hung an enormous screen. Visitors here are invited to replay the rapid-fire ill-thought decisions made by the Decider himself in no more than five seconds time. Who was the greatest menace during the W. Administration? An image of Saddam Hussein appears on the large screen, supposedly reflecting the collective vote of those seated.

The Fox-newsroom pace of this kiosk, a permanent display, is far more rapid than that of the painting exhibition on the other side of Freedom Hall. According to the New York Times, G. W. told a private gathering that, while he once rushed through the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia in 30 minutes, he now liked to spend hours in museums ruminating over the individual brushstrokes of paintings. This would seem to reflect a slower, more thoughtful, and perhaps even brooding temperament on the part of the once Great Decider.

Does painting make him a more ethical person? Perhaps not. But then again, giving slow thoughtful attention to the details of a painting might lend itself to greater deliberation over the complexities of the world.

—CHARISSA N. TERRANOVA

The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy

George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum

Through June 3