Through more than 70 pieces from Berlin’s esteemed Neue Nationalgalerie, the latest exhibition at Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum gives American audiences a rare opportunity to explore the artistic developments within one of history’s most infamous periods. Modern Art and Politics in Germany: 1910-1945 runs through June 22. The exhibition holds an unwavering lens to its subject matter, illuminating astonishing stories from the tumultuous and fraught period via an extraordinary collection of works from German artists who rarely receive such mainstream recognition in the United States.

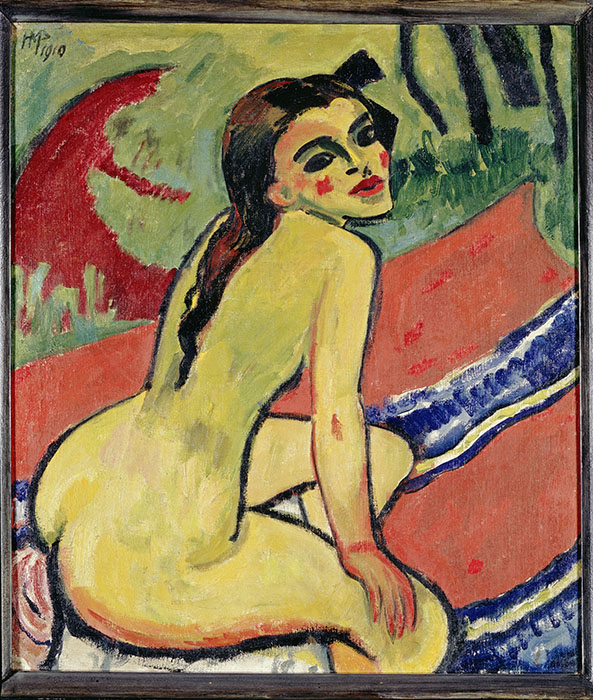

Divided into six sections, each exploring a different side of the artistic and political landscape of early-to-mid 1900s Germany, the exhibition begins with German expressionism. One of its most unique pieces, quite literally, is Conrad Felixmüller’s The Orator No. I, Otto Rühle. The piece is a fragment of a work depicting Rühle, a Marxist who was kicked out of two communist parties, intensely delivering a speech to workers. “When the Nazis came to power, Felixmüller thought he better destroy this painting for fear of getting in trouble,” Shackelford says, describing the artist’s decision to cut out the painting’s head and destroy the rest of it. The fragment survived the war, and Felixmüller would later use it as a reference to recreate his original piece alongside archival photography. The resulting painting concludes the exhibition in the final section titled Before and After.

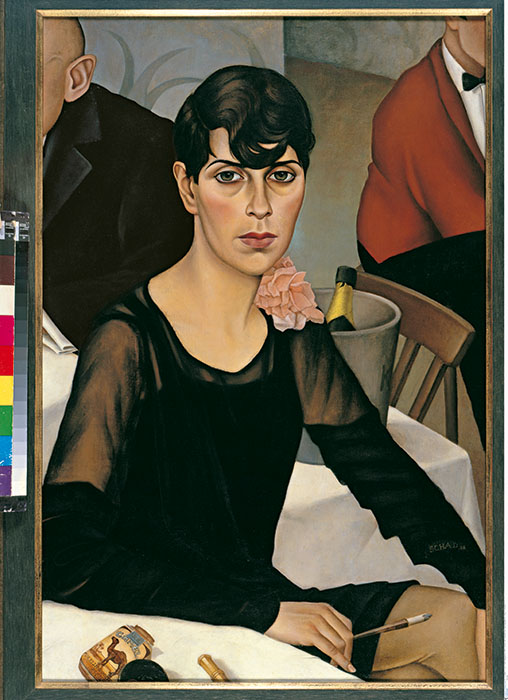

The exhibition’s second section diverges from expressionism by exploring the New Objectivity movement defined by sharply realistic depictions of modern life in the new Weimar Republic. The section features a number of captivating portraits, including Christian Schad’s acclaimed Sonja.

The following section, International Avant-Gardes, explores the German impact on the broader art world. It includes Woman Sitting in an Armchair by Pablo Picasso. The artist received his first major exhibitions outside of France in 1913 courtesy of German art dealer Heinrich Thannhauser. The Kimbell owns a painting of Thannhauser by Lovis Corinth, which marks one of a trio of portraits depicting influential German art dealers, each of whom was forced to flee the country due to their Jewish heritage. “When I saw this section developing around the subject of German dealers and foreign art, it made every sense to include the Kimbell’s painting,” Shackelford says.

In many ways, the next section, titled Modes of Abstraction, continues to explore the effect the Nazi dictatorship had on the art world. The section focuses on abstract artists and the influence of the Bauhaus, the German state art school that counted a number of esteemed artists, designers and architects among its faculty. Many of the artists featured in the section, including Hannah Höch, Rudolf Belling and Paul Klee, had work labeled as “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime, a term applied broadly to works that appeared modern or abstract that marks a common theme throughout the exhibition as a whole.

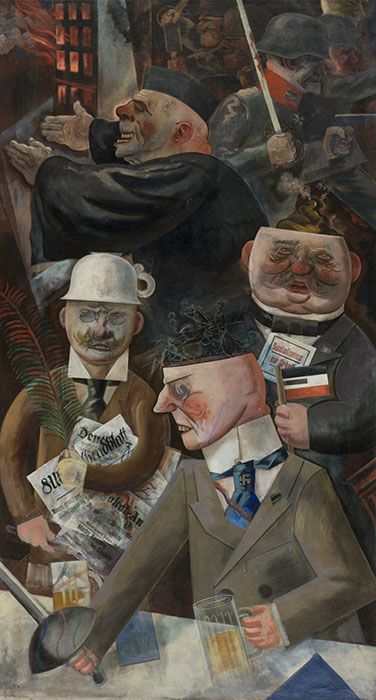

Those themes of persecution and repression continue in Politics and War, which encompasses both World Wars and includes works of protest as well as stark, poignant reflections on the atrocities experienced in the wars among its many prominent pieces. Pillars of Society by George Grosz serves as one of those social commentaries, satirically depicting and criticizing those so-called “pillars” of Weimar Republic society in 1926. Shackelford calls the massive 6-foot-5-inch piece “one of the most important pictures in the show.”

1 ⁄6

George Grosz, Pillars of Society, 1926, oil on canvas. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © 2024 Estate of George Grosz / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Kai Anette Becker © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

2 ⁄6

Christian Schad, Sonja, 1928, oil on canvas. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © Christian Schad Stiftung Aschaffenburg / ARS, New York, 2024. Photo: Jörg P. Anders © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

3 ⁄6

Wassily Kandinsky, Hornform, 1924, oil on cardboard. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

4 ⁄6

Lyonel Feininger, Teltow II, 1918, oil on canvas. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn Photo: © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

5 ⁄6

Max Pechstein, Seated Girl, 1910, oil on canvas. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © Pechstein Hamburg/Tökendorf / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2024 Photo: Klaus Göken © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

6 ⁄6

Kurt Günther, Portrait of a Boy, 1928, tempera on wood. Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo: © Neue Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

The exhibition’s final section, Before and After, looks at the aftermath of World War II in the art world. It includes three paintings by acclaimed German artist Max Beckmann, including a self-portrait he painted while in exile in Amsterdam. Similarly, Salvador Dali’s Portrait of Mrs. Isabel Styler-Tas, which the artist painted while in exile in America, is displayed in this section as well.

Overall, Shackelford says this exhibition marks a rare opportunity to see such an expansive collection of German art outside of a select few destinations across the globe. Moreover, it allows new audiences to learn about many talented German artists whose contributions rarely receive popular recognition despite creating captivating works during such a calamitous period.

—BRETT GREGA