The internet is peppered with a handful of articles about the artist Michael Tracy, the majority of which take either his extravagant but gruff personality or his 2024 passing as their subject matter. Whether it’s the New York Times site visits, Artforum’s emotive review, or the Houston Chronicle’s report of “death, conflict, extinction, disaster,” these stories will tell you almost everything you, dear reader, need to know.

Almost.

But why exactly is the San Antonio museum championing this artist who was “exiled” from Houston?

For starters, Matthew McLendon, Director and CEO of the McNay, tells me that the McNay presented Tracy’s first museum exhibition in 1971, which speaks to the museum’s heritage of championing emerging, marginalized artists. That kind of support is reflected by the current exhibition as well.

What took place between these book-ending exhibitions is the stuff of legacy and legend, to which the dynamic nature of The Elegy of Distance alludes, at least in part.

After more than a decade of living in San Ygnacio, Tracy founded the River Pierce Foundation in 1990, welcoming artists from different cultures to immerse themselves into the local environment as Tracy did. Christopher Rincón, Director of the River Pierce Foundation and President of the Michael Tracy Foundation, says that River Pierce was a resource center during the 20-year period that the artist worked on the art in The Elegy of Distance. Essentially, the exhibition would not have been possible without the archival nature of the organization’s work, or guidance from the artist himself.

The foundation’s inaugural event that year was “a procession, a performative action based on the annual Via Crucis (Way of the Cross) liturgy practiced in San Ygnacio for hundreds of years,” Rincón explains. Other contemporary artists were commissioned to set up interventions along the route. “The final stop involved the burning of Tracy’s piece Cruz: La Pasión as it was floated into the Rio Grande and it became a beacon of destruction and transformation in protest to the problems of immigration that we still deal with today.”

1 ⁄6

Michael Tracy

Speaking with the Dead n.d. (detail)

Acrylic on canvas stretched on wood (7 panels)

60 H x 48 W inches (each panel)

Courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

Photograph by Matthew Fuller Photo, courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

2 ⁄6

Michael Tracy

El Canto de Todos: Honoring the Suffering of Migrants, 1982 - 1986

Acrylic and metal leaf on wood with tin coronas

42 H x 28 W x 12 D inches

Courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

Photograph by Matthew Fuller Photo, courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

3 ⁄6

Michael Tracy

Flower Sacrifice, 1988

Gilded wood, swords, brass milagros, silk, and fresh flowers 42 H x 35 W x 35 D inches

Courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

Photograph by Matthew Fuller Photo, courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

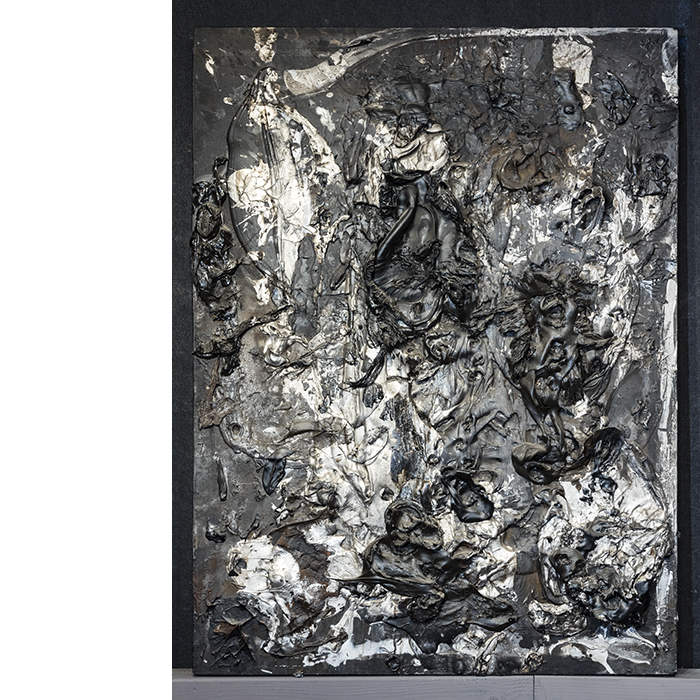

4 ⁄6

Michael Tracy

In the Mexican Garden (detail), 2005

Acrylic on cloth mounted on wood (2 panels)

72 H x 45 W inches (each panel)

Courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

Photograph by Matthew Fuller Photo, courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

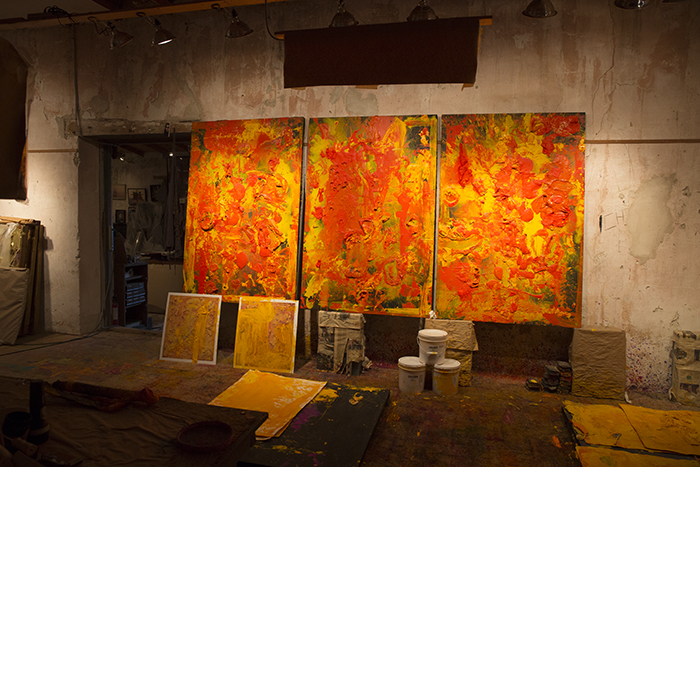

5 ⁄6

Michael Tracy’s studio in San Ygnacio, Texas. Photograph by Bryan Schutmaat.

6 ⁄6

Library, The Michael Tracy Foundation, San Ygnacio, Texas. Photograph by Matthew Fuller Photo, courtesy of Michael Tracy Foundation

While The Elegy of Distance doesn’t include performance per say, the installation is nothing short of dramatic—rightfully so, considering Tracy’s interests, artmaking sensibilities, and the influences of religion, spirituality, and Catholicism on his work. Large-scale sculptures and assemblage reference altars and stations of the cross while heavy impasto abstract paintings offer up fleshy textures that bring to mind the messiness of life. Brightly colored walls of red and yellow immerse museum visitors into a setting that sparks feelings of both celebration and alarm.

“Because the work is largely abstract, and the titling of the work is often quite evocative, viewers are transported to different worlds, whether it be to India, to Mexico, or to different planes of consciousness, because that was something Michael was very interested in,” says McLendon. “Also, Michael was really a great colorist—he understood color in a profound and sophisticated way, and many of these canvases are riots of color. He pushes the boundaries of accepted notions of what beauty is, and that’s exciting.” Additionally, the exhibition features an original soundscape from Omar Zubair, whom Tracy had commissioned to produce a soundtrack for the Trevino-Uribe Rancho, now a National Historic Landmark owned by the River Pierce Foundation and open to the public.

Rincón remembers, as a twenty year old, asking Tracy how he “did it.” “He chuckled because he knew I was asking a very complicated question but he knew the right response. He told me, ‘Just keep making your work. Don’t ever stop.’

—NANCY ZASTUDIL