Gustave Caillebotte, Nude on a Couch, 1880.

Oil on canvas. 51 x 77 in.

Minneapolis Institute of Art, The John R. Van Derlip Fund.

An Unsung Impressionist’s Distinctive Vision Comes to Light at the Kimbell

Don’t skip Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, which opens Nov. 8 at Fort Worth’s Kimbell Art Museum, no matter how sick you think you are of Impressionism. In fact, the more you’ve overdosed on Monet, Renoir, and other familiar figures, the fresher and stranger Caillebotte’s strikingly modern, quasi-photographic, and arguably queer sensibility will look in this focused selection, which Kimbell deputy director George T. M. Shackelford co-curated with Mary Morton of the National Gallery of Art, where I saw the show this summer.

Before attending to queer readings of Caillebotte’s work, which have gained currency in recent years and seem vindicated by the visual evidence, it’s worth noting what critics of his day observed—that paintings like the seminal Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877), with their combination of scrupulous detail and seemingly arbitrary compositional elements, had a lot in common with photography. Paul Sébillot wrote that “this painting, despite its contestable qualities, startles without being moving; it gives an idea of what photography will be like when the means are found to replicate colors with their intensity and finesse.”

That prophecy aside, if you’ve seen even one of Parisian photographer Charles Marville’s contemporaneous black-and-white shots of any post-Baron Haussmann boulevard, with what catalog contributor Sarah Kennel calls “its sharply receding orthogonals, its sense of immeasurable space, and its palpable emptiness,” you’ll recall it often during this show—which could almost be called The Photographer’s Eye—even when Caillebotte turns his attention indoors.

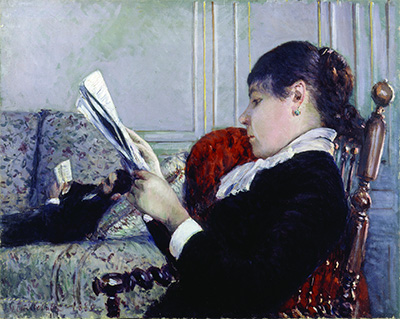

Take the claustrophobic Interior, a Woman Reading (1880), in which the reader, shown in profile from the waist up as she dominates the foreground, hilariously gets photo-bombed (canvas-bombed?) as she lifts her newspaper to reveal a literally downsized husband, who’s about a third the size he should be. Caillebotte further enhances the perspectival trickery by oversizing the divan on which the man, who’s also reading, reclines. “Overstuffed comfort may have been modern, but in Caillebotte’s interiors the overlapping physical, psychological, and gendered connotations of soft furnishings routinely work against the subject’s ability to feel comfortable,” writes catalog contributor Elizabeth Benjamin in the aptly titled essay, “All the Discomforts of Home.”

The giant divan returns in Nude on a Couch (1880), one of Caillebotte’s rare and decidedly anti-erotic treatments of the female nude. Unlike roughly 99 percent of her predecessors in the Western tradition, she comes across as un-idealized, oblivious to the viewer and not even slightly on display. She is not a new possession for the painting’s presumably male buyer. Indeed, there may not have been a presumed buyer, as the independently wealthy Caillebotte bought far more paintings than he sold, which may account both for his relative obscurity and for some of his artistic candor. In 1884, you didn’t replace the traditional toilette subject—a female nude—with a muscular man flexing his glutes while toweling off, as Caillebotte did in Man at His Bath, if sales were a paramount concern.

Contrasts in the way Caillebotte, who never married, depicts male and female flesh (look how the light plays across the shirtless workers’ sinewy bodies in his realist masterpiece The Floor Scrapers, 1875), his overwhelming preference for painting men, and the way décor-gone-wild amplifies domestic tensions in many of his interiors, are just a few of the reasons queer theorists have found ample fodder in his oeuvre. Another is the cruisy vibe in paintings like The Pont de l’Europe (1876), in which a bourgeois flâneur seems to ignore his female companion to gaze intently at a working-class man leaning at the railing, and the related On the Pont de l’Europe (1876-77). Once you’ve picked up on it, you can’t un-notice it.

—DEVON BRITT-DARBY