Sometimes the final act brings resolution and neatly ties up an epic tale. Sometimes the final act leaves little resolution and gives an opening for a follow-up, or nothing at all.

“It’s about seeing where we are right now, the impact of all of this history and how we see ourselves going forward. How can we go forward with this weighted history?” Harjo, who lives in San Antonio, said.

Sara-Jayne Parsons, exhibition curator and director of the Art Galleries at TCU, doesn’t see it as a conclusion, however. “There’s still a personal kind of reckoning or grappling. But then the show itself is not going to be like, ‘here’s all the answers,’” she said.

1 ⁄4

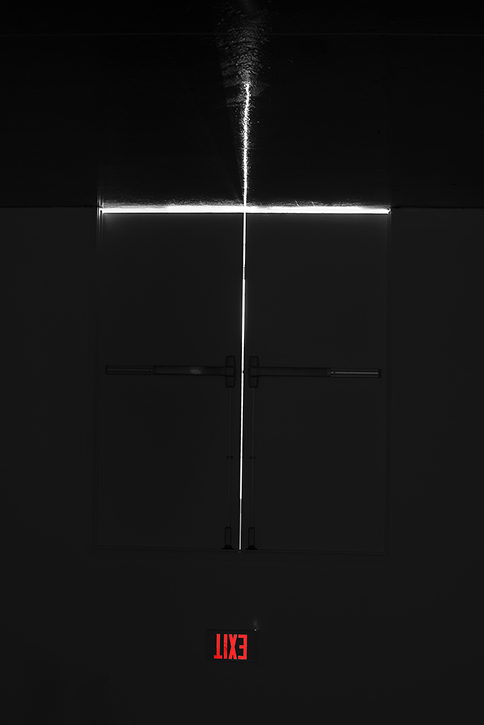

Joe Harjo, EXIT, 2019, digital archival print, 40 x 27 inches

2 ⁄4

Joe Harjo in the studio, a working image from a photo session, 2025. Photo courtesy of the artist.

3 ⁄4

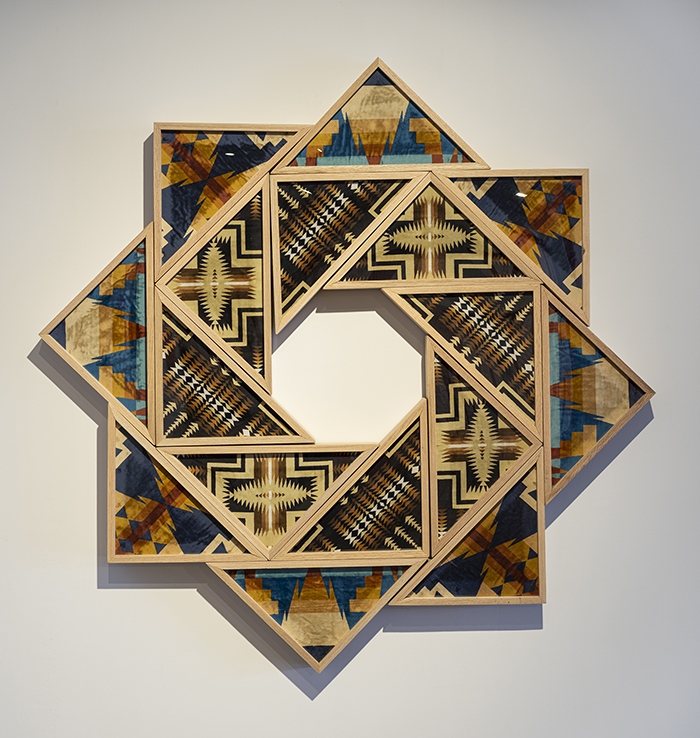

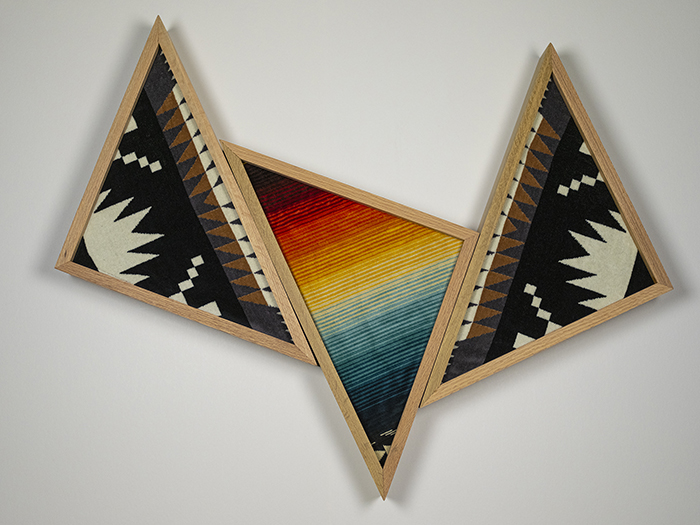

Joe Harjo, When the Roses Bloom Again, 2024. 16 custom memorial flag cases, 16 ceremoniously folded Pendleton beach towels, 78 x 78 inches

4 ⁄4

Joe Harjo, Waiting for the Birds to Sing, (detail), 2025, sculptural installation

He’s showing how colonization is about more than a land grab and a vision. It’s a culture shift.

But he had to build up to that tension. The first act, Indian Removal Act I: American Progress, which ran at the Galveston Arts Center in Galveston in 2023, was an introduction. It featured black and white self-portraits like Mark of the Beast, 2019, showing the back of his head, hair tied into two braids, with the hairline shaped as a cross.

The second act, Indian Removal Act II: And She Was, which ran last year at The Contemporary at Blue Star in San Antonio, featured resilient women facing a shift from matriarchal to patriarchal structures and forced conversion to Christianity. He was among the characters featured in emotive self-portraits and the video A Heretical Act of Resistance: Walking with Babygirl, 2024. In the ten minute video, Harjo walks along a road in Okemah, Oklahoma, where his great-grandmother Babygirl was relocated. Each step follows her life and the larger Native American struggle of the past. But he keeps an eye toward a more hopeful future.

For these eloquent sculptures, which are among his best works, he folds and fits into the triangular frames reserved for American flags given to soldiers who died. The first, Honor and Loss in the Time of Annihilation (Attempted), 2023, is a cross-like structure constructed from 12 indigo towels, ceremoniously folded and encased in boxes. He’s reclaiming Indigenous patterns, expanding, even if he could verge on heresy to some for replacing the flags in the boxes. As for the cross shape, “I think of them as memorial flag cases that are arranged to look like a cross.”

He is unafraid to explore his themes via other media as well with other symbols. He takes on the United States flag, with its red, white and blue stripes and white stars.

The third and final act, he said, is about “reclaiming some agency and just saying, ‘we’re going to tell our stories when we want to tell them as many times as we want to tell them and how we want to tell them. We’re going to own our history, and we’re going to determine what we look like going forward.”

While not the end, one of his underlying messages is hope and inspiration for young people.

And going forward, he said, “I hope that young native people take the reins and just run the hell out of it. I want them to go forward and be what we can be unapologetically.”

—JAMES RUSSELL