A Jerome Robbins gem gets top billing in the advertising. But each work in Houston Ballet’s “In the Night” program opens a window into the company and its history.

Lila York’s Celts is a rousing showpiece that especially highlights the company’s men, while also commemorating artistic director Stanton Welch’s longtime efforts to promote choreography by women. And Welch’s own Maninyas not only explores how people behave as romantic relationships evolve, but it commemorates a crucial moment in the relationship between the Australian native and Houston Ballet.

Let’s begin with Maninyas. “It’s a very personal ballet of mine that I feel like I’ve had with me for a very long time,” Welch says.

Maninyas—Welch’s first American commission, created for San Francisco Ballet—dates back to 1996, when he was an Australian Ballet dancer branching out into choreography. Based on a violin concerto of the same name by Australian composer Ross Edwards, it centers on five couples.

“Throughout the ballet,” he continues, “these five couples have different relationships and interactions with each other. At the very end, these veils which they’ve been moving through the whole time fall away. They’re in this open space with the person they’re committed to, and go forward into a different kind of relationship.”

San Francisco Ballet treated Maninyas to “an amazing cast. It was all-star people,” Welch recalls. But the premiere run’s audience included someone with a different influence: Ben Stevenson, then Houston Ballet’s artistic director. Stevenson later contacted the young choreographer.

“He said, “I’ve seen Maninyas, and I really like it. I’d like you to come (to Houston) and make a new work,’” Welch recalls. That yielded Welch’s Indigo, which introduced Houston Ballet’s audience to him.

Welch had already encountered the company and city: Urged by his mother, an Australian ballerina who had known one of Houston’s ballet mistresses since they were students at the Royal Ballet School, Welch had come to town for two weeks of ballet classes when he was around 18 years old. When he returned for Indigo, he says, the company impressed him anew.

1 ⁄5

Nozomi Iijima and Christopher Gray in Stanton Welch’s Maninyas. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2014). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

2 ⁄5

Nozomi Iijima and Ian Casady in Stanton Welch’s Maninyas. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2014). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

3 ⁄5

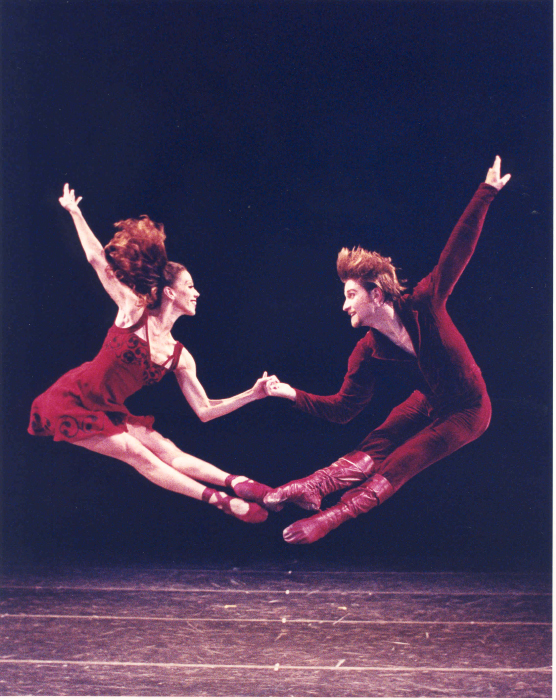

Pamela Lane and Ian Casady in Lila York’s Celts. Photo by Jim Caldwell (2004). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

4 ⁄5

Houston Ballet Principal Karina González and Joseph Walsh in Jerome Robbins’s In the Night. Photo by Leonel Nerio (2011). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

5 ⁄5

Houston Ballet Principal Jessica Collado and Christopher Coomer in Stanton Welch’s Maninyas. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2014 ). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

“That felt wonderful,” all the more so because Welch had just had the opposite experience, he recalls, with the Royal Danish Ballet in Copenhagen. “I came from that dark, cold place, where no one wanted to work, to the heat and the green of here, and these dancers who were so hungry to make a ballet. I loved it.”

After Houston Ballet hired him as artistic director in 2003, Welch brought Maninyas to his new company—including for a German tour in 2017. Meanwhile, the work contributed to other Houston Ballet careers: It gave Jessica Collado “one of her first breakout lead roles” on the way to becoming a principal dancer, he recalls. When Welch staged Maninyas for Tulsa Ballet, he encountered Karina González, who he brought to Houston. She’s now another principal.

Houston Ballet dancers’ knack for transforming themselves into whatever a particular work needs, Welch says, explains why they’re cut out for Jerome Robbins—many of whose works are in the company’s repertoire. Robbins demands performers who are “really detailed, down to the eyebrow rise, down to when you laugh, when you look back. Tiny, micro things,” he explains. “That’s what makes the work timeless.” He likens it to the art of the spoken theater.

As a dancer with the Australian Ballet, Welch himself performed In the Night, which Robbins set to four Frédéric Chopin nocturnes. While it isn’t a story ballet, Robbins gave its couples distinct identities.

“The first couple is innocent love, new love—tentative,” says Welch, who belonged to that pair onstage. “The middle couple is smart and sophisticated, and they have a rapport. And the third couple has wear and tear and emotions and baggage. I think that’s a lovely progression of romance and stories and relationships.”

Depicting all that, Robbins’ choreography is “remarkably intricate and precise,” he continues. “I love that as a choreographer, and I loved it as a dancer. And (at Houston Ballet now) everyone wants to be in it desperately, of course. But it’s only three couples. … So I think it will be the stars of the organization.”

Celts will balance that out, unleashing the company en masse. Premiered by Boston Ballet in 1996, it’s a celebration of Irish dance and spirit, set to recordings by the likes of The Chieftains.

York, an alumnus of Paul Taylor Dance Company who moved into choreography around 1990, “has been a part of Houston Ballet’s history and lineage for a while,” Welch says. The company performed three of her works—Celts among them—during Stevenson’s time. “And she’s iconic for me,” Welch adds, thinking back to his beginnings as a choreographer. “Everywhere I went to work, there were Lila York ballets.” He saw audiences “going crazy” for Celts.

Celts’ climax introduces “kind of a Mother Earth figure, with this universe spiraling around her,” Welch says, and the entire company takes off in “enthusiastic, joyful dancing.” It represents “community and being together, and using Irish dancing—with ballet, of course—to … build this kind of eruption. That’s what we all are, that’s what humanity is. It’s a great ending to an evening.”

Celts belongs to a long series of works by female choreographers that Welch has brought into Houston Ballet’s repertoire. He has seen the effects within the company’s own ranks.

“In the 20 years I’ve been here, I’ve always had choreographic workshops,” Welch says. Early on, “if we put up a list, the men would have no problem writing their name on the list. There would be very few women, and I would go and encourage them.” Around 10 years ago, a change began. “Now, when you put up a list, half the names are women,” Welch continues. “It takes a long time just to show that there’s a path. And (amid) the younger kids in the school now, there sometimes are more women than men choreographing at the academy level.”

In the main company, soloist Jacquelyn Long “made a lovely piece for us,” Welch adds. “She’s young and fearless, and that’s exactly what we want. … It’s about making sure the younger generation starts choreographing—feeling what it’s like—as young as possible, and that they see people they like and admire who are ahead of them. That helps.”

-STEVEN BROWN