Michelle Handelman, Beware the Lily Law, 2011.

Video, 27:47 minutes.

Courtesy the artist.

Art can be radical. There’s nothing new about this statement because art has always been radical in some form or function. Art has long intermingled with politics, whether praising leaders and institutions or dissenting against them. When life itself is political, something more and more people have come to realize lately, the art no longer seems radical or revolutionary. More often than not, it really just feels like public opinion, a reflection of beliefs from some circle of society that its opponents might dismiss as easily as the art itself. The overt caricatures no longer satisfy; the not-so-subtle satire becomes par for the course, an expected reaction to an easy target.

When artists find unexpected ways to confront injustice, whether by pointing to it or working to correct its impact, art once again sparks dialogue if not direct action. On view at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) through Jan. 6, 2019, Walls Turned Sideways: Artists Confront the Justice System showcases artists who work to directly address a complex, disjointed, and flawed system within the United States. Organized by guest curator Risa Puleo, the exhibition features over 40 artists from across the country.

Puleo and the CAMH have arranged the exhibition in sections that examine the many components of the system these artists are targeting. They range from profiling and arrest into the courtroom for processing, through incarceration to an exit that can be either hopeful or dreadful.

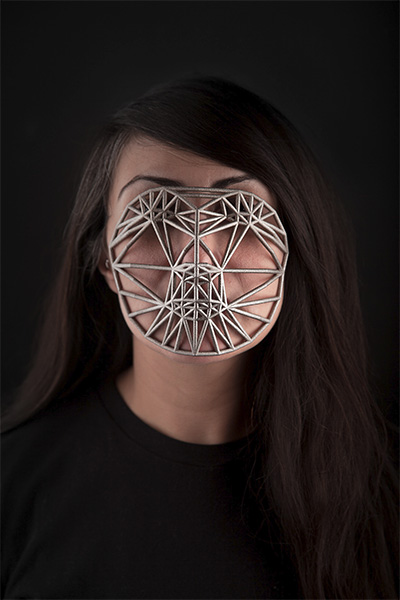

In a series of works titled Face Cage, Zach Blas utilizes facial recognition software, a tool likewise being utilized by police and government agencies on a regular basis. He used this software to analyze his own face as well as those of his collaborators, flattened them into 2D grids and designed head cages reminiscent of those used in the past to punish and humiliate rather than rehabilitate individuals. The works are presented in a group of 4 monitors, each with a video of someone adorned in their face cage and set against a black backdrop. For some, they simply sit resting around the eyes. Others seem weighted as they strip the wearer of their identity. Akin to the facial recognition fiasco Apple faced, though, the software does not recognize all faces equally. With the technology not optimized to scan the specificity of certain skin tonalities, Blas’s work points to a fault in profiling common to the justice system.

Dread Scott’s project Wanted, in which he address the criminalization of American youths, points to harassment in current policing techniques – the police sketch. Presented initially in Harlem, New York, the project consists of a series of wanted posters with depictions of youths from the community accompanied by descriptions of the behaviors that entice police harassment. One poster reads “The male was observed standing on corner with other males.” Another, “The police allege that the suspect moved suspiciously when officers approached…” Through the works Scott argues that the United States has criminalized an entire generation of POC youth through laws that officials claim deter crime but in reality provide police with added authority and normalize harassment.

Tucked into the back of an erected structure, a prison cell has been built to give visitors an intimate experience with Beware the Lily Law by Michelle Handelman. The video uses the Stonewall Riots as a jumping point to discuss the issues faced by transgender inmates, often placed in prisons based on the gender assigned to them at birth. One inmate flashes between prison and life and their heyday of celebration and drag at the Stonewall while another mournfully explains his longing for top surgery and why he’s been placed in a women’s prison. Handelman imagines in this installation a reality these inmates don’t always experience, shared space, stating that they typically wind up in a form of solitary confinement for their own protection.

If you follow the works according to the process established within the justice system, you find yourself among works both hopeful and dreadful. There are only so many ways you can find yourself out of prison, after all. The lighter side showcases artists who engage inmates in the reentry process, working with them to reimagine life and establish a vision for the future. Gregory Sale, in collaboration with members of the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, created the project Future IDs to do just that. Participants recreate ID cards representative of where they hope to go. Some simply show desire to return to their families while others bear new titles, dream jobs they strive for.

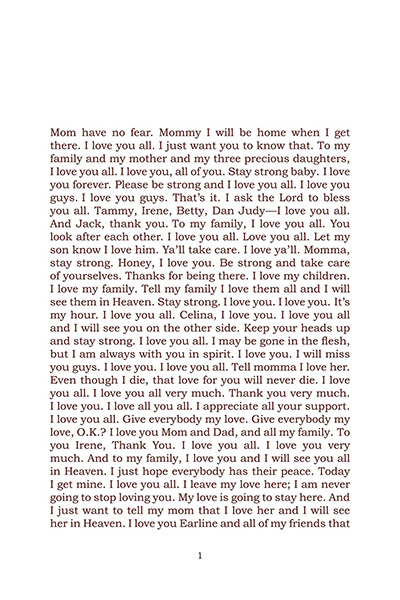

For other inmates, though, these futures aren’t possible. They stay in prison on life sentences or fall victim to the death penalty. In his work Last Words, Luis Camnitzer has gone through death row records of inmates’ final utterances before meeting their fate, culling statements of love and running them together into an extended verse of grief and acceptance.

Puleo’s exhibition is a heavy and necessary education of the realities that people experience within the justice system. The works within stagger between subtle and heavy-handed but all contribute to a greater conversation about reform that is desperately needed across the board.

—MICHAEL McFADDEN