Climb the stairs to the second level of the Law Building at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and you encounter two silent, black-and-white films, projected on the wall near the entrance to Tamara de Lempicka, the first major museum retrospective of the Art Deco pioneer and one of the 20th century’s most underappreciated artists. Three-and-a-half minutes of looping footage to the left captures Lempicka, her lover and muse Ira Perrot, and an unidentified fop smoking, drinking, and looking fabulous in the Jardin du Luxembourg. Always hyper-conscious of her appearance, Lempicka repeatedly gazes directly into the camera. On the right, a 1932 newsreel shows Suzy Solidor, the lithe and beautiful proprietor of a famous lesbian nightclub, posing nude for Lempicka at her easel.

Born Tamara Rosa Hurwitz on June 28, 1894, in either Warsaw, Saint Petersburg, or Moscow, the trajectory of Lempicka’s biography is complicated and until her death in 1980, filled with gaps. Glamorous, wealthy, and free-spirited in her pursuit of sensual pleasure, Lempicka may initially come across as shallow—more of an “illustrator” than a “serious” artist. But the quality of works on view in the MFAH exhibition, on view through July 6, 2025, makes it clear that Lempicka is worthy of such an in-depth reappraisal of her art.

Tamara de Lempicka premiered at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, and the MFAH is its second and final stop. Originally conceived by Lempicka scholar Gioia Mori and FAMSF curator Furio Rinaldi, the exhibit includes over 90 paintings, sketches, and studies, including drawings by Lempicka’s teacher and mentor André Lhote, and several dramatic, cinematically staged photographs of Lempicka.

In 1918, the Russian Revolution and the arrest of her first husband, Tadeusz Lempicki, forced Tamara and her young daughter, Marie-Christine, nicknamed Kizette, to flee their home in Saint Petersburg. They made it to Paris, where Tamara was somehow able to secure Tadeusz’s release. To survive, she sold some of her jewelry, and later, began painting commissioned portraits of the city’s “minor aristocrats and wealthy patrons,” as well as bohemian women. “Tamara may have loved women for their bodies and men for their power,” says Greene. “Most of her male lovers were to her financial or social or professional advantage. But that’s nothing new.”

Unique to the Houston exhibit is the integration of objects from the MFAH’s permanent collection of modern design, including perfume bottles, glass vases, and even a small waste basket, each carefully placed to engage and complement the art, and create a cool, elegant vibe for visitors. “If you put a pink vase in a room with nudes, it makes that vase very sexy,” says Greene.

1⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Saint-Moritz, 1929, oil on panel, Musée des Beaux-Arts d’Orléans, inv. no. 76.12.1. © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY

2 ⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of Ira P., 1930, oil on panel, private collection. © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY.Image © 1969 Christie’s Images Limited

3 ⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of a Young Woman in a Blue Dress, 1922, oil on canvas, private collection © 2025 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY, Image © 2023 Christie's Images Limited

4 ⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Kizette on the Balcony, 1927, oil on canvas, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne / Centre de création industrielle, Paris, gift of the artist, 1976, inv. AM1976-113. © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY. Digital Image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

5 ⁄8

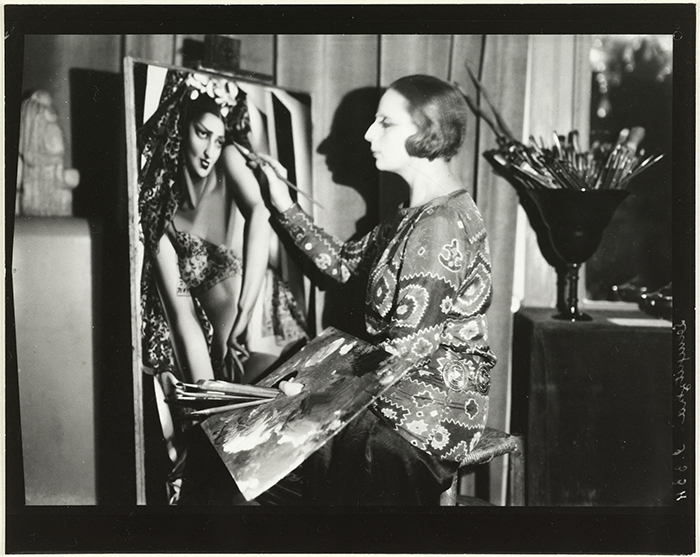

Thérèse Bonney, Tamara de Lempicka working on the portrait “Nana de Herrera,” c. 1929, gelatin silver print. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Source: Ville de Paris / Bibliothèque historique 4C-EPF-006-00701.

6 ⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Still Life of Fruit and Draped Silk, 1949, oil on canvas board, Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin, gift of Luis Aragón, 1986, inv. no. 1986.174. © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY

7 ⁄8

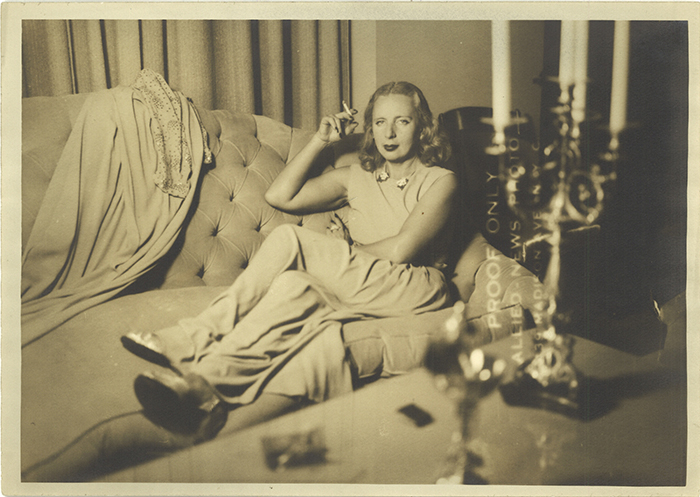

Unidentified photographer, Tamara de Lempicka at home in New York, c. 1943, Tamara de Lempicka Estate.

8 ⁄8

Tamara de Lempicka, Young Girl in Green (Young Girl with Gloves), c. 1931, oil on board, Centre Pompidou, purchase, 1932, inv. JP557P. © 2024 Tamara de Lempicka Estate, LLC / ADAGP, Paris / ARS, NY. Digital image © CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN- Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Tamara’s collectors were by and large men who were drawn to the sensuality of her paintings of women, and women with women. One such work is La Belle Rafaëla, a painting Lempicka redid many times of a shapely, full-figured woman touching herself purely for her own erotic pleasure. “The squishy parts of the female body . . . that if you lean this way, something else falls that way, I think that’s something she’s very attuned and sympathetic to,” says Greene. “It’s not just about how a woman’s body looks, but how it feels.”

—CHRIS BECKER