Carter E Foster.

Image Courtesy Carter E.

A+C TX Q&A with Carter E. Foster

Carter E. Foster, former Steven and Ann Ames Curator of Drawing at the Whitney Museum of American Art, was recently appointed Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs and Curator of Prints and Drawings at The Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin. A+C contributor Laura A. L. Wellen corresponded with Foster through email, addressing some of his experiences at the Whitney as well as his appreciation of the Old Masters, his curiosity about the Austin music scene, and more.

LAURA WELLEN: I’m interested in your training as a specialist in Old Master drawings and how that manifests itself in your work with 20th century and contemporary artists. This kind of long term connection across broad swaths of time is an exciting way of approaching the medium of drawing and linking it to other media.

CARTER FOSTER: When I came to the Whitney Museum of American Art, I found that in working regularly with living artists, I could have really great conversations about art history. Most artists are deeply appreciative art historians in their own right. And one of the aspects of working with prints and drawings as a curator is that those collections often span that range of time in museums: if you’ve been trained in “print room” culture, you naturally think about a broad swath of art history rather than a narrower historical period.

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, c. 1560

Pen and brown ink with brush and brown wash over traces of black chalk on cream antique laid paper

22 3/8 x 16 7/16 in.

Blanton Museum of Art, The Suida-Manning Collection, 1999.

LW: Can you describe the new position you will be taking at the Blanton Museum of Art? It bridges Curatorial Affairs, and Prints and Drawings. Is this a new position they’ve created?

CF: I’ll be working with the talented staff of the Julia Matthews Wilkinson Center for Prints and Drawings, Jeongho Park and Kristin Holder, to continue their already deeply established mission of sharing that important collection with University of Texas and other Austin communities, as well as doing rotations from the collection in dedicated galleries. So the collection of prints and drawings will be my direct curatorial area, while as Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs I’ll be working on long term and strategic planning for both the exhibition program and the overall direction and development of the entire collection.

LW: As the first Curator of Drawing at the Whitney, among many other things, you worked to develop the drawing study room. Tell me a bit about the study of drawing, what you implemented there, and what you hope to bring to the Blanton. It strikes me as a uniquely intimate way of engaging with art, to see works on paper in this kind of environment, and a special opportunity for UT-Austin students and researchers.

CF: What I helped the Whitney do was really just open a center that was up to current museum standards in this area. Now the Whitney’s important collections are finally accessible in a way they were not before, to Whitney staff as well as outside researchers, curators and scholars. I was able to take advantage of the knowledge of many colleagues in the field who had already thought about what makes a study room work and what does not, so hopefully the Whitney now has a state of the art facility for the future. The Blanton already has the Wilkinson Center, a beautiful, state of the art study center for its collection of prints and drawings. Studying works on paper is in fact a very intimate way to look at art, and study rooms provide that access, which I understand is heavily taken advantage of by the Austin and UT communities. When you are looking at a print or drawing up close and unframed, you are about as close to the artist as you can possibly get, which is what makes places like the Wilkinson Center inspiring for visitors.

LW: Can you tell me a bit about the strengths of the Blanton’s prints and drawings collection, for those who aren’t familiar with it? I know it’s still very early, but I wonder if you already see certain areas to build on within the collection?

CF: Certainly, Old Master prints and drawings, which roughly means works created between the early Renaissance and the mid 19th Century, are a strength to be celebrated and enhanced. My own specialty within that field is French drawings and prints, so I certainly plan to use that expertise to help build the collection. But I also plan to take advantage of the entire curatorial staff’s expertise in their various areas as we consider how best to add really meaningful works on paper. Certainly making acquisitions is, for me, one of the most enjoyable and rewarding aspects of curatorial work—its impact is lasting.

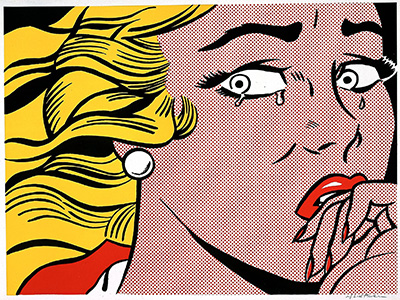

Crying Girl, 1963

Three-color offset lithograph

18 1/16 x 24 in.

Blanton Museum of Art, Gift of Charles and Dorothy Clark, 1976.

LW: The new Whitney Museum’s inaugural exhibition, America Is Hard to See, which you co-curated, made some impressive (often overlooked) connections between artists. It offered many fresh ideas about how we think about art history and its threads or resonances. Was there a visual connection in that exhibition that you were especially invested in, that was really unexpected or providential?

CF: Two in particular come to mind: one was the juxtaposition of a sculpture by the African American artist Richmond Barthé with a painting by the poet E. E. Cummings. The Barthé piece, African Dancer, is conservative in form in that it is a figurative work. The cummings painting is totally abstract, by contrast. But by presenting a beautiful black female body in the tradition of the Western canon the way he did in 1933, Barthé was actually being transgressive. And both pieces, while seemingly oppositional as objects (flat colorful abstraction vs. monochrome figurative and fully three dimensional), are about the power of sound and music and how that can be visually translated.

I was also very pleased that we showed two drawings by James Castle alongside works by Grant Wood, Andrew Wyeth and other extremely well known figures of the thirties and forties. Castle worked in isolation in Idaho and his achievement still yet is not fully understood. Yet I’m convinced that in a hundred years he will be seen as one of the great American artists of that era.

Christ Preaching, called La Petite Tombe, c. 1652

Etching, drypoint, and burin on Japanese paper

6 1/8 x 8 1/8 in.

Blanton Museum of Art, purchase through the generosity of the Still Water Foundation, The Dean of the College of Fine Arts, and the Archer M. Huntington Museum Fund, 1995

LW: You’ve worked in Cleveland and Los Angeles, New York and now Austin. I love this variety between big urban centers and smaller regional cities. What are you looking forward to about being in Texas, apart from the Blanton? And what are you curious about?

CF: I’ve said to myself before: “If Texas was a country, I’d want a passport.” There is a genuine friendliness and a kind of “can-do” attitude, which is just immensely appealing. Texas is also full of great museums and is an incredible place for cultural philanthropy in general. Most Texas museums are relatively young when compared to the established institutions of other places in America, yet they are world class. Texans combine ambition with sophistication and doing so has put the state and its cities on the cultural map in a big way. We see this in Austin and at the Blanton with their interest in pursuing the realization of Ellsworth Kelly’s building, Austin. I just look forward to engaging with this great Texas spirit and community—one I felt a rapport with the first time I visited. As for curiosity—well, I can’t wait to dive into the Blanton’s collections and to take advantage of UT’s other amazing resources—the massive library system and the Ransom Center in particular. And certainly I’m curious to check out what must be the many, many nuances of the Austin music scene.

—LAURA A. L. WELLEN