Dance artists are shaped by the work they dance, and the relationship between the dancer and the dance-maker is extremely potent when it comes to what we see on stage. More and more, the dance field is acknowledging the creative agency of the dancing body, the body as an archive of all that a person has danced, and how that knowledge contributes to the richness of a dancer’s artistry. When a dancer learns a new work it enters their dance DNA, in that it becomes part of the choreography that lives within their bodies.

For many of the company’s new dancers it will be their first taste of these outstanding dance-makers’ work. For veteran performers, they get another chance to deepen their experience with a choreographer’s work.

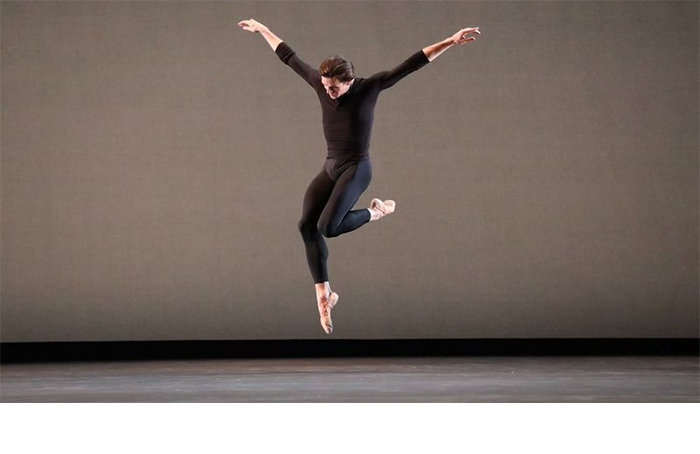

Who better to chat about dance DNA than Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh, now entering his 20th season with the company? Walsh can boast a deep dance DNA well that includes works by Stanton Welch, George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins, Jiří Kylián, William Forsythe, Justin Peck, Alexander Eckman, Wayne McGregor, Christopher Wheeldon, Twyla Tharp, Hans Van Manen, Glen Tetley, Christopher Bruce, Anthony Tudor, Nacho Duato and Serge Lifar, Melissa Barak, Aszure Barton, Edwaard Liang, Mark Morris, James Kudelka, Nicolo Fonte, Melissa Hough, and Garrett Smith.

In many ways, Walsh is a quintessential Houston Ballet dancer, able to seamlessly traverse the continuum from classical roles to the most contemporary work happening in ballet today.

Now fluid in Welch’s choreographic language, Walsh recalls his baptism into Welch’s work with his experience performing Maninyas, which returns later this season.

“There was a physical aggression that I really responded to,” says Walsh. “There’s this animalistic, grounded quality where you’re still using your ballet technique, but with a sense of abandonment along with attack and release.”

Welch created Velocity, with a score by Michael Torke, in 2003 for The Australian Ballet. The ballet is a perfect example of Welch’s hard driving, yet delicately ornamented style. It’s a powerful kinetic signature, which is why it’s such a crowd favorite.

1 ⁄7

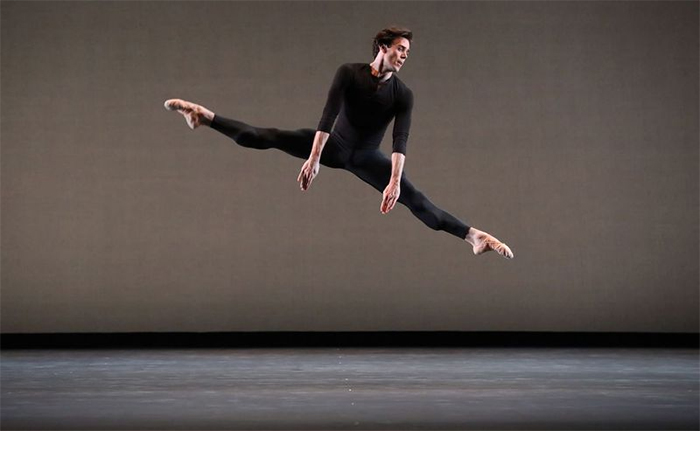

Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh in Aszure Barton’s Come In. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2019). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

2 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh in Aszure Barton’s Come In. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2019). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

3⁄ 7

Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh in Aszure Barton’s Come In. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2019). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

4 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principal Connor Walsh with former Principal Melody Mennite in Aszure Barton’s Angular Momentum. Photo by Lawrence Elizabeth Knox (2019). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

5 ⁄7

Houston Ballet Principals Karina González and Connor Walsh with artists of Houston Ballet in Stanton Welch’s Velocity. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2014). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

6 ⁄7

Artists of Houston Ballet in Connor Walsh ’s A Joyous Trilogy (in flight). Photo by Lawrence Elizabeth Knox (2022). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

7 ⁄7

Choreographer Silas Farley and Artists of Houston Ballet rehearsing The Four Loves. Photo by Amitava Sarkar (2024). Courtesy of Houston Ballet.

He sees a theme of relationships in Welch’s ballets. “There’s often this tension about whether it’s a positive relationship or a negative relationship. In Velocity, it’s about your relationship with dance, your relationship with ballet, your relationship with your body. His works require a great amount of strength, but also tremendous attention to detail, so there’s always tension between precision and attack.”

Walsh encountered an entirely different choreographic process with Canadian choreographer Aszure Barton, who created Angular Momentum for Houston Ballet in 2012. Barton was already a world phenomenon when she landed in Houston Ballet’s studios to workshop the new piece. I spent a day watching the company adjust to Barton’s idiosyncratic vocabulary for a story in Pointe Magazine. I distinctly remember Walsh’s ultra-focused concentration. The room was steeped in Barton’s tiny details that made her movement pop.

Walsh describes the process. “For Aszure, the ballet is created in the studio. There’s a lot of workshopping and cutting and pasting. She’s constantly sketching. And then when you look at her work, it looks so fluid and so seamless. She creates a beautiful sensitivity in her sense of detail.”

Walsh returns to Barton’s work dancing in Come in, a ballet for 13 male dancers, with a score by Vladimir Martynov, originally created for Mikhail Baryshnikov in 2006.

Walsh reflects on revisiting Come In at this milestone in his career. “I am in the place of passing things on. The central figure has this gift and in the end, gives the gift away. It feels like some sort of swan song.”

Silas Farley’s world premiere Four Loves, inspired by C.S. Lewis’ book of the same name, with a commissioned score by Kyle Werner, completes the trilogy. Farley, a former dancer with New York City Ballet, is currently serving as the Armstrong Artist in Residence in Ballet at Southern Methodist University’s Meadows School of the Arts. Farley has created a one-act ballet with 27 dancers, which makes perfect sense since his first work for the company, Rococo Variations, Op. 33, proved a hit during the 2022 Jubilee of Dance.

Although Walsh has not danced Farley’s work, he can certainly comment on what this rising young choreographer brings to the mix. “There’s buoyancy to his work, you can see a lighter classicism, and his youthful energy in the piece,” explains Walsh. “I can just see his passion for ballet vocabulary within his dances. He watches class with a smile on his face and you can see that joy within his work.”

As in most mixed reps, there’s something for everyone, in that the curatorial palette is a diverse one. Walsh agrees, elaborating on each ballet’s distinct qualities. “Velocity is aggressive and direct, Come in is calm and sensitive, and The Four Loves is airy and floating.”

He also realizes that having such a deep well of dance DNA could be an obstacle. How do young choreographers become informed by the choreographers that exist in their bodies without being held back? “I am still working on how to find my own voice,” says Walsh. “I don’t want my ‘dance parents’ to define me.”

I imagine that I am not alone in anticipating how and when Walsh will develop as a choreographer. He has the discipline and the DNA to become a strong choreographic voice. As for this moment in his career Walsh simply wants to relish year 20 with a full heart. “I’m trying to not be stressed about imperfections. I want to focus on being present within the works and to bring something as valuable as I can.”

—NANCY WOZNY