A mixture of blues and greens sweeps across the canvas, colliding with and scaling mountain ridges formed by scraps of terry cloth. At the peak, a yellowish hue cascades down the other side of the cloth. From a distance, the painting seems like some far-off scene of celestial bodies. Up close, it appears almost like a textured map.

“My process allows for different textures of material to be thought of in a way that disguises, blends, and covers tracks,” said Martinez, describing their work. “These pieces of cloth create a passage from one material to the next.”

Born in the Rio Grande Valley, Martinez grew up in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where they are currently based. Throughout their life, art played a major role, with Martinez focusing their energy on art from an early age.

“From preschool all the way through everything, I was encouraged about it, so I kept following it,” they stated. “Around the age of 10, I really knew and started to work with more serious art supplies and took it to the next level. Since then, I’ve gone through a whole trajectory of drawing, painting, metal sculpture, and welding.”

“The Valley is important to my work, identity, thinking, and all those things,” Martinez expanded. “You cross a checkpoint going to the Valley, so the boundaries weren’t clear to me growing up, and the concepts of boundaries and borders come into the work in plentitude. There are aspects that deal with landscape, texture, dryness, dustiness, and color.”

From the physical border between Texas and Mexico to the perceived border between painting and sculpture, these lines play a role in how we consider or identify ourselves, others, environments, and objects around us.

“The experience of my work is trying to grapple with what the materials are and what they’re doing,” Martinez mused. “Are they being destroyed or remade? It’s about these dualities and where you are in the moment since everything is always in flux.”

That idea of remaking, destroying, and repurposing is central to Martinez’s studio practice as the terry cloth utilized in their paintings are the materials they use to clean the studio. From one purpose to another, they remain a part of the process.

1 ⁄6

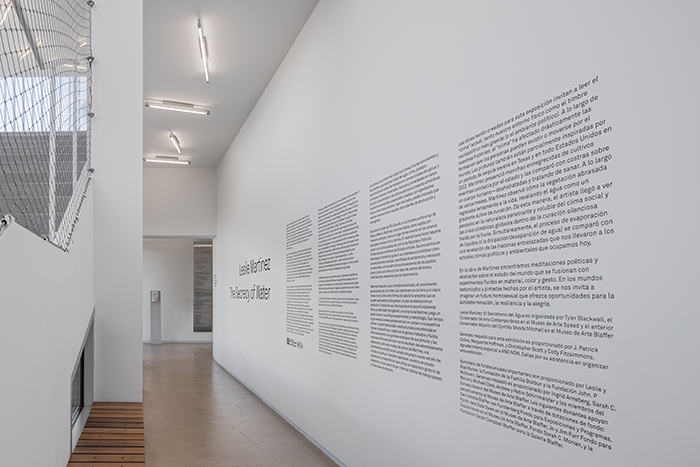

Leslie Martinez: The Secrecy of Water at the Blaffer Art Museum; installation photos by Francisco Ramos.

2 ⁄6

Leslie Martinez: The Secrecy of Water at the Blaffer Art Museum; installation photos by Francisco Ramos.

3⁄ 6

Leslie Martinez: The Secrecy of Water at the Blaffer Art Museum; installation photos by Francisco Ramos.

4 ⁄6

Leslie Martinez, In the Arcs of Time Ripped to Shreds, 2023. Fabric and paper scraps, charcoal, fine ballast, pumice and acrylic on canvas, 96 x 144 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and AND NOW, Dallas.

5 ⁄6

Leslie Martinez, Blazing Bounty, 2023. Fabric and paper scraps, charcoal, fine ballast, pumice, and acrylic on canvas, 96 x 144 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and AND NOW, Dallas.

6 ⁄6

Leslie Martinez, Every Fiber of the Beast, 2023. Fabric and paper scraps, charcoal, fine ballast, pumice, and acrylic on canvas, 96 x 144 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and AND NOW, Dallas.

In discussing the process, Martinez spoke of the studio as an incinerator, with materials entering the studio in one form only to exit as part of a painting.

“The work is everything it takes to make the work,” they stated. “There’s a lot of processing and material grading because everything has its future role, so there’s a futurity-based thinking without a plan. The material may not be used for years, but it’s understood that it will be used.”

In considering the scale and nature of the paintings, Martinez’s work explores the space of the canvas, finding expansion within confinement.

“There’s this weird thing about the question of wholeness and finitude,” they stated. “You enter the space of the canvas, which people think is contained, finite, and you realize it’s not confined, it’s boundless and expansive. Scale can allow a person to have a more total experience.”

As they continued to explore these ideas, the work and the materials expanded to being parts of the whole instead of a finite completion, “moving away from that infinitude and toward the infinity of possibility.”

How can the way you question what you look at be replicated in the way you experience life? If you sit with the work and experience it, all the questions you seek are the questions you’re asking about what you see.

“We live in a world of entrenchment where people don’t understand others,” Martinez wondered, “but what can the ways you naturally engage with the curiosity of a painting say about an individual’s ability to understand another person?”

When your body shares a space with a painting, it can transform your understanding of what you see. What does that say about our ability to engage with difference in the world?

—MICHAEL McFADDEN