Even if you’ve never been to Spain, you’re likely to be familiar with some of the country’s most stunning signature artistic marvels, such as the elaborate retablos, or altarpieces, found in churches and cathedrals throughout the region. These opulent, stately displays of devotional paintings and sculptures portraying Christ, the Virgin Mother, and other saints rose to prominence during the Renaissance, during a time when the Spanish empire was experiencing unprecedented expansion and cultural fertility. It’s also the era that produced Alonso Berruguete, one of Spain’s most revolutionary sculptors whose artistic genius literally and figuratively brought Spanish art to new heights through his towering, ornately designed retablos.

Currently, the Meadows Museum at SMU in Dallas is the home of Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain, the first exhibition devoted to the artist to be displayed outside Spain; it is on view through January 10, 2021.

Organized with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration with the Museo Nacional de Escultura in Valladolid, Spain, the collection of approximately 45 paintings, sculptures and works on paper gives visitors the opportunity to discover Berruguete not only as sculptor, but also as painter, designer, draftsman, and architect.

“As I hope becomes clear to visitors, Berruguete’s work is immediate, expressive, and entirely distinctive,” says Wendy Sepponen, curator for the Meadows installation, who began working on the exhibition in 2016 as a curatorial fellow in the sculpture and decorative arts department at the National Gallery of Art. “These objects themselves have so much to say about the people that assembled, carved, painted, and gilded them, and there are new details and surprises to discover in every one, even after all this time.”

Though Berruguete spent more than a decade of his young adulthood developing his artistic ingenuity in Italy in the presence of Michelangelo and other contemporaries, his own style is distinct from that of the Italians. In his sculptures, bodies are elongated and exaggerated to convey expression and heightened emotion, characteristic of the style of Mannerism, which rose in popularity in the early 16th century. And then there’s that glorious hair… perhaps best illustrated on Abraham in The Sacrifice of Isaac, the exhibition’s striking introductory sculpture that was originally displayed in the niche of a Benedictine monastery altar. “He’s known for what I call the ‘Berruguete wind,’” says Sepponen, describing the piece with a grin. “The hair always looks like it has a fan on it somewhere.”

Turning into the first room of the gallery, the journey of Berruguete’s life begins with a few works representing Spain’s artistic landscape during the artist’s youth at the turn of the 16th century. Most notable in this section is The Virgin and Child Enthroned, a painting by Alonso’s prolific father, artist Pedro Berruguete, a well-known practitioner of the Hispano-Flemish style. An aspect of the Meadows exhibition distinguishing it from the previous installation at the National Gallery is the availability of space; the Meadows has more of it, enabling them to incorporate additional pieces from the museum’s permanent collection. Sepponen says it’s an opportunity to enrich and amplify the context of Spanish art during Berruguete’s youth.

1 ⁄ 8

2 ⁄ 8

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), Old Testament Prophet (Isaiah?), 1526–1533. Polychromed wood with gilding. Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, CE0271/035. Image © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor.

3⁄ 8

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), The Sacrifice of Isaac (detail), 1526–1533. Polychromed wood with gilding. Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, CE0271/013. Image © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor.

4 ⁄ 8

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), Roundel with Male Head, 1526–1533. Polychromed wood with gilding. Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, CE0271/075. Image © Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid (Spain); photo by Javier Muñoz and Paz Pastor.

5 ⁄ 8

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), Sepulcher of Cardinal Juan Pardo Tavera, 1561. Carrara white marble. Hospital Saint John the Baptist, Toledo. © 2019 Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic—im. 05583046 (foto Mas C-80351/1934).

6 ⁄ 8

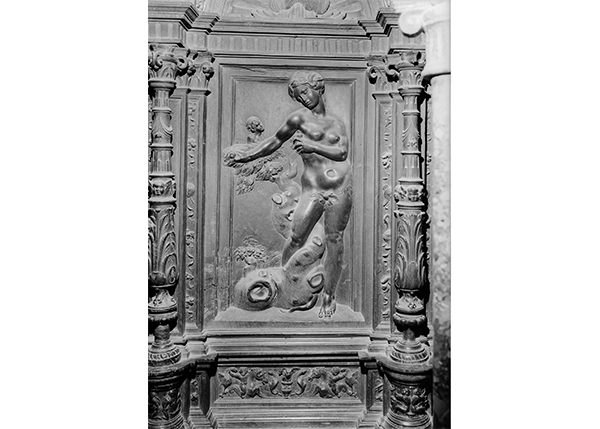

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), Eve, 1539–1542. Walnut, Toledo Cathedral. © 2019 Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic—im. 05583045 (foto Mas C-76421/1934).

7 ⁄ 8

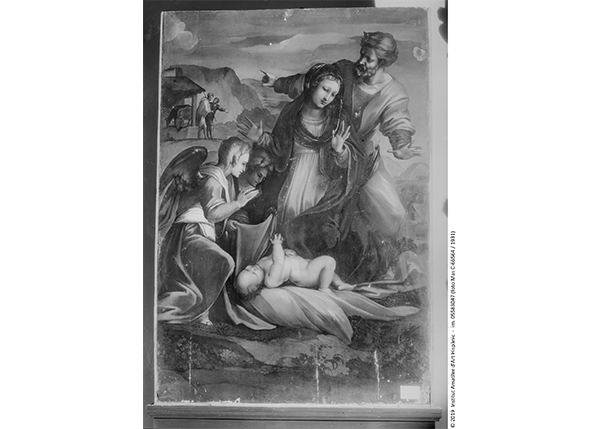

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), The Nativity, 1526–1533. Oil on panel. San Benito el Real, Valladolid. © 2019 Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic—im. 05583047 (foto Mas C-66564/1931).

8 ⁄ 8

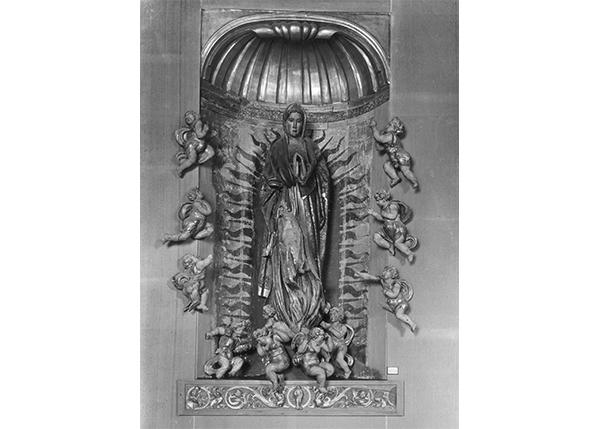

Alonso Berruguete (Spanish, c. 1488–1561), The Virgin and Angels, 1526–1533. Polychromed wood. San Benito el Real, Valladolid. © 2019 Institut Amatller d’Art Hispànic—im. 05583041 (foto Mas C-26027/1951).

Further into the room, visitors come upon Berruguete’s earliest-surviving sculpture, Ecce Homo, depicting Christ at crucifixion. The exaggerated, sinewy limbs and attenuated facial features serve as early indicators of what would become the artist’s unequivocal trademark.

The exhibition flows into the period Berruguete spent in Italy, a pivotal point of his artistic evolution. Among the highlights in this section are two paintings from his time in Florence, along with a few examples of his drawings on paper. “You can start to get a sense of how he’s working up compositions and this is a very Italian practice,” explains Sepponen, who adds that the drawings serve as examples of how Berruguete took what he learned in Italy to implement in his Spanish workshops. Because the history of drawings among Spanish Renaissance artists is minimal at best, Berruguete’s corpus is considered the first and largest collection in terms of Spanish art history.

“So all of this sets you up for the next gallery,” says Sepponen during a walk-through, as she rounds the corner into a room glowing with painted and gilded sculptures. As the obvious centerpiece of the exhibition, the items in this gallery come from the high altarpiece of San Benito el Real in Valladolid. One wall contains a loosely-reconstructed portion of the altarpiece (which was originally about seven stories high) to give visitors an idea of how the sculptures were first installed. A single, long bench sits in the middle of the room. “It is a room meant to be experienced, sat with, and gone over slowly,” says Sepponen. Indeed, the surroundings give admirers a sense of the majesty and scale of the original retablo, in addition to the meticulous planning, designing and passion that went into its creation.

The final stretch of the exhibition seems like an after-dinner mint following the sumptuous main course of the sculpture room. Sepponen says that it’s also another part unique to the Meadows installation, which dives deeper into some of the questions that Berruguete’s work naturally draws out around the processes and techniques used for gilding and making polychrome sculptures. A bust and collection of panels loaned from the National Gallery of Art demonstrate the procedures step-by-step, beginning with raw wood, followed by the stages of applying a primer sealant, various layers of gesso, and eventually, paint. Another panel displays an X-Ray image of The Sacrifice of Isaac to solve the mystery of whether nails or glue were the chosen methods of fastening the wood pieces together.

Additional didactics provided at the conclusion of the tour include a map of Berruguete’s travel trajectory, sites from where his materials were sourced, and locations to where his works went. A separate room provides an informative film showcasing works by Berruguete that cannot travel.

Meanwhile, an adjoining gallery contains a companion exhibition, Berruguete Through the Lens: Photographs from a Barcelona Archive. This collection of 31 black-and-white images from the Meadows’ Archivo Mas collection shows Berruguete’s masterpieces in their original contexts before the Spanish Civil War of the early 20th century.

Both exhibitions were scheduled to open in March, but were put on hold in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Luckily, Sepponen, who wrapped up her tenure as the 2018-20 Mellon Curatorial Fellow for the Meadows Museum in October, was still able to see her years of planning come together.

“The simplest satisfaction is also the greatest: to finish installing the exhibition and to share it with the public,” she says. “The exhibition was postponed for nearly six months due to the pandemic, and they have been months filled with uncertainty in so many respects. To be able, finally, to introduce the artist and his extraordinary works to the public, whether in person or through our robust calendar of virtual programs, has been immensely rewarding.”

—AMY BISHOP