They were pivotal to Europe’s transformation during the Enlightenment, leaders in the excavation and new discoveries of Pompeii and elsewhere. Those discoveries inspired design that is even seen to current times.

You most likely haven’t heard of them.

Professor and University of Texas at Dallas’s Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History director Michael Thomas showcases his and others’ decades-long research into the excavation and findings following Mount Vesuvius’s eruption in 79 CE.

“What’s unique about this show is it is the first exhibition looking at the court’s impact on architecture, its impact on production and their obsession with the volcano,” Thomas said.

But as the exhibit unfolds in six rooms, the king, who was pushed by his wife Maria Amalia, ordered excavations of nearby sites covered in volcano ruins, most notably Pompeii. His son Ferdinand IV continued their legacy.

Maria’s influence is understated. “There are some moments and discoveries in this period we should make about her,” Thomas said. But it was a family effort and a sign of royalty’s commitment to their adopted home.

“It shows how the excavation took on a life of its own,” said Thomas. Given the Bourbons are not household names, the show opens with family portraits. Antonio Joli’s landscape painting The Royal Procession of Piedigrotta, seen from the West sets Charles and Ferdinand riding in a carriage against the Naples cityscape.

1 ⁄6

Second Style wall painting with monochromatic landscape, mid-first century BCE, Reale Scudiera (Royal Stables) of Portici. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale de Napoli, inv. 8593. Pigment on plaster, 77 x 76 3/8 in. (195.6 x 194 cm). Photo © foto Giorgio Albano.

2 ⁄6

Wall painting fragment showing a woman (so-called Flora), early first century CE, Villa Arianna, Stabiae. Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale de Napoli, inv. 8834. Pigment on plaster, 14 15/16 x 12 5/8 in. (38 x 32 cm). Photo © foto Giorgio Albano.

3 ⁄6

Antonio Joli (Italian, 1700–1777), Departure of Charles of Bourbon for Spain, seen from the Harbour, 1759. Oil on canvas, 50 3/8 x 80 ¾ in. (128 x 205 cm). Napoli, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. Photo © Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte.

4 ⁄6

Anton Raphael Mengs (German, 1728–1779), Portrait of Ferdinand IV of Bourbon, 1759. Oil on canvas, 70 7/8 x 49 5/8 in. (180 x 126 cm). Napoli, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. Photo © Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte.

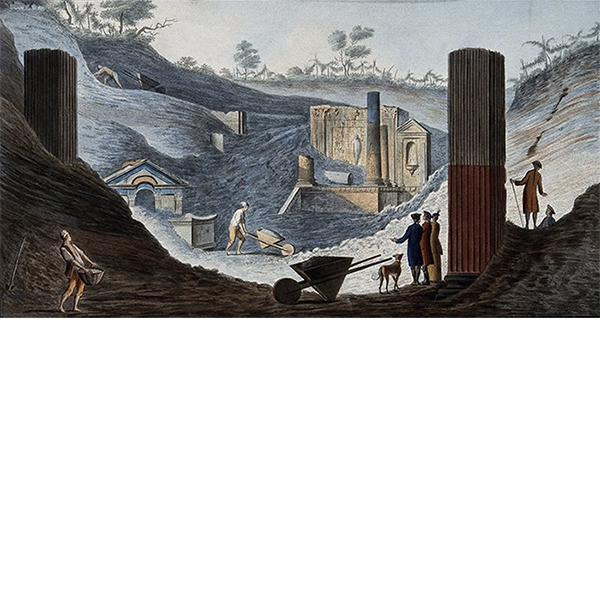

5 ⁄6

Pietro Fabris (Italian, active 1756–1779), The Discovery of the Temple of Isis at Pompeii, buried under pumice and other volcanic matter, c. 1776. Hand-colored etching on paper 8 3/8 x 15 ½ in. (21.5 x 39.2 cm). Wellcome Collection, London. Photo Public Domain Mark. Source: Wellcome Collection, London.

6 ⁄6

Pierre-Jacques Volaire (French, 1729–1799), Eruption of Mount Vesuvius on the Ponte della Maddalena, 1782. Oil on canvas 51 1/8 x 90 1/8 in. (129 x 260 cm). Napoli, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte. Photo © Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte.

The 18th century was an important time for archaeology, Thomas said.

“What excites me is bringing art from the court as well as their excavations,” he said. Among the objects found near the Portici royal palaces are 18th century renditions of ancient artifacts in biscuit porcelain, 19th century copies of the famous bronzes from the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum and frescoes depicting sacred landscapes alongside imagery of priests conducting rituals, including worship of the goddess Isis.

Commissions inspired by the Bourbon legacy are also included to make the case this was not a novelty project for the wealthy. The most notable is by a British diplomat to Naples. Sir William Hamilton commissioned Pietro Fabris to document the volcano’s eruptions for his book in his publication, Campi Phlegraei: Observations on the Volcanoes of the Two Sicilies.

“People don’t think of the 18th century as momentous,” Thomas said. “But you have Pompeii capturing the public’s imagination and the birth of Neoclassicism, with Charles and Maria as patrons. It’s an overlooked 100 years of European history.”

—JAMES RUSSELL