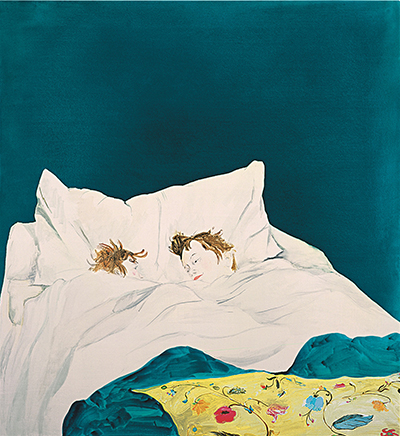

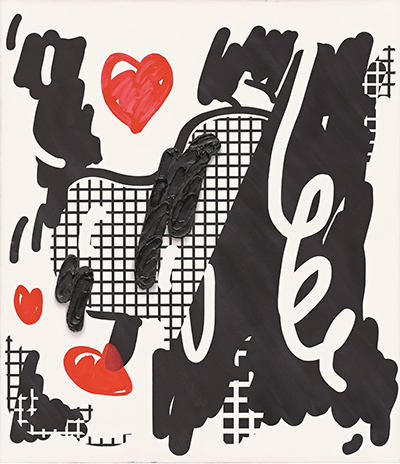

Laura Owens, Untitled, 1995, acrylic, oil, enamel, ink, and felt-tip pen on canvas, Collection of the artist.

Courtesy the artist / Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York and Rome; Sadie Coles HQ, London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

© Laura Owens.

Serendipity often plays a large role in life; it can in the art world, too. Laura Owens’s mid-career survey Laura Owens, is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art through July 29, after a run at the Whitney Museum. Scott Rothkopf, curator-in-chief of the Whitney and co-curator of its exhibition Laura Owens, started his art career by interning at the DMA.

The DMA’s iteration of the exhibition will contain many but not all of the works from the New York showing, plus some additions. “Laura’s shows are very site-specific; she pays a lot of attention to the architecture of the setting,” says Dr. Anna Katherine Brodbeck, DMA’s Nancy and Tim Hanley Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art. “At the same time, this is a mid-career retrospective, so it is important to tell the story of that career.”

Some readers may know that the story of Owens’s career is not without controversy. She and her dealer Gavin Brown have been implicated in the gentrification of the Boyle Heights neighborhood in Los Angeles; activists protested at the VIP opening of her show at the Whitney.

Owens is a prolific artist, manoeuvring seamlessly between abstraction and figuration, and between different painting styles. Amid this rich oeuvre, Brodbeck and her team want to highlight certain themes that are consistent throughout the artist’s career, most importantly her treatment of painting alongside installation, and the collaborative nature of her work.

One gallery at the DMA will combine both: an installation based on collaboration between Owens and artist Jorge Pardo, whose work uses elements of art, design and architecture. Three bedroom sets designed by Pardo will complement three paintings by Owens, with mirrors enhancing the three-dimensionality of the space. “It will be like an art-furniture showroom,” explains Brodbeck.

According to Brodbeck, “Laura’s generosity as an artist really stands out.” An early painting of 1995 shows a picture gallery with the artworks painted in by some of Owens’s artist friends. She could have used any fictional images but chose to pay homage to those to whom she feels close. But something else also catches the eye in this work. The perspective is warped, with an unusual horizon: the white floorboards take up most of the picture plane, the wall only a small diagonal strip of color at the top. It is the opposite of a bird’s-eye view, as if a tiny creature nesting on the gallery floor had presented us its awe-inspiring vista. In Owens’s paintings something is always slightly off.

For another example (all Owens’s works are Untitled), the horizon sits at the bottom of the canvas, like a small strip of sea, making way for a seemingly infinite sky. Flying high in the sky are two black birds. They cast strange shadows, as if the canvas itself is a mirror. And on closer look, a tiny abstract dot floats in the sky, black like the birds, and complete with its own little shadow.

Brodbeck tells me such works are typical. “Owen’s work is very playful and joyous. Encountering her work goes beyond the passive experience of viewing a painting. People are always due to respond to the work on different levels; there’s something for everyone and the more time you spend with the work the more it gives to you.”

Sometimes there is an interactive element as well. There will be a few paintings in the DMA show that allow the visitor to send a text message to the painting, which will then dutifully respond with its own recorded message.

Playfulness also comes across also in Owens’s attention to the materiality of her work. She often incorporates craft, such as embroidery, buttons or cloth, to give her paintings extra texture. Her painting styles itself add texture too, especially in her abstract canvases, combining older silkscreen techniques with digital imaging technologies like Microsoft paint, impasto brushwork with newspaper ads. As Brodbeck explains, “Owens has a very interesting way of layering. Strong colors and a graphic quality belie a meticulous technical skill.”

There was a period when Owens painted in a more traditional way, creating images that have an organic, drawn quality, almost bordering on illustration. This coincided with the period that she became a mother, but also with political unrest after 9/11. It is as if she wanted to retreat a little from the bold, life-affirming, happy-go-lucky quality of her earlier works, into a more reflective and comforting style. “Laura made references to works of old worship, and created a version of the Bayeux tapestry: a medieval conflict, alluding to the bellicose. The interpretation of such works is more oblique. To honour these quotations, the works from this period will be displayed in a salon-style hanging.”

Owens’s work has sometimes acquired the label of appropriation, but Brodbeck is quick to counter that notion. “I don’t think appropriation is the right word, but she does cross-reference a lot of historical painting. For example, the first time she incorporated human figures in here work she was inspired by Toulouse Lautrec. Laura samples, synthesizes, and takes inspiration from the history of painting.”

The DMA’s installation of the survey will try to emulate that artist’s own variety, richness, and dialogue with earlier art. Her work will be spread out over the museum, some of it as an intervention in the existing permanent collection. “You can follow her paintings like a breadcrumb trail throughout the museum,” says Brodbeck. There will be benches with custom-made covers designed by Owens. Her art even makes it way outside the walls of the museum, through the covers of the exhibition catalogues—each of the 8,000 copies comes with a unique silk-screen cover, handmade in Owens’s studio.

This brings us back to Owens’s generosity. “She is very generous to the spectator,” Brodbeck says. “There is something about her painting that goes beyond what typical painting does.”

—SABINE CASPARIE