Jamie Wyeth, Kleberg, 1984. Oil on canvas, 77.5 x 108 cm (30 . x 42 . in.)

Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1992.164

© Jamie Wyeth

Photography courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Jamie Wyeth at the San Antonio Museum of Art

Jamie Wyeth painted President John F. Kennedy, befriended Andy Warhol, and covered the Apollo moon shot for NASA, but he is most at home in the rural environs of Pennsylvania’s Brandywine Valley and along the rocky shores of Maine. While the 68-year-old artist may be the country’s most popular realist painter, his work is often lumped in with his father’s and grandfather’s as the absolute antithesis of modernism, a living link to Old Weird America.

Spanning more than 50 years of his career, Jamie Wyeth, on view through July 5 at the San Antonio Museum of Art opens with his childhood drawings, traces his development as a portrait painter, examines his stint in The Factory with Warhol in New York, contemplates the rural scenes that pay homage to his family’s legacy and details his emergence as a great animal and bird painter.

Descended from a line of realist painters extending from the Civil War era, Jamie Wyeth belongs to the “Brandywine tradition” that encompasses the work of Howard Pyle (1853-1911), who was a mentor to his grandfather, Newell Convers “N.C.” Wyeth (1882-1945), famous for illustrating classic novels such as Treasure Island, and his father, Andrew Wyeth, who painted the iconic Christina’s World, yet spent much of the latter part of the 20th century as modernism’s whipping boy.

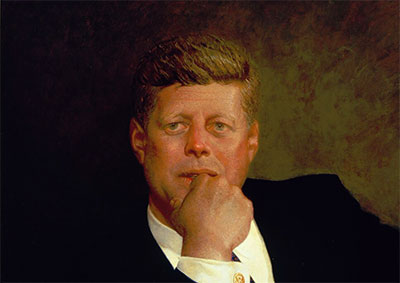

Jamie Wyeth has struggled to forge his own identity while remaining true to the family’s distinctive brand of highly detailed, emotionally evocative American rural realism. His portrait of President Kennedy cemented his status as national celebrity, although the commission was ultimately rejected. At the exhibit’s opening, Wyeth said the Kennedy family wanted “a blonde, blue-eyed American boy.” However, the portrait has been recognized for capturing Kennedy’s thoughtful introspection and the psychological drama of the times.

Crucial to Wyeth’s development as an artist is his portrait of the arts impresario Lincoln Kirstein, which led to introductions to the Russian ballet dancer Rudolph Nureyev and to Warhol. An entire gallery is devoted to Wyeth’s Factory period, examined in depth in the 2006 exhibit Factory Work: Warhol, Wyeth, Basquiat at San Antonio’s McNay Art Museum. Besides a Warhol portrait of Wyeth at SAMA, two miniature, three-dimensional dioramas made by Wyeth recreate scenes from The Factory, including Warhol’s dining room furnished with a glowing TV, magazines, a bar and colorful Fiestaware. Wyeth made miniature versions of Warhol and his friends using GI Joe doll bodies topped by lifelike heads carefully sculpted in Plasticine.

But Wyeth soon left New York behind to return to his rural roots. One of the key works on view at SAMA is Bale, an amazingly detailed painting of a hay bale. Wyeth contends his paintings would be “just as interesting hung upside down,” because he uses abstract elements to form his realism. At first glance, Bale could be 19th-century folk art, but up close a universe of whirls, circles and expressive marks is revealed. Wyeth said he considers his “landscapes to be portraits,” building up layers of realistic detail to reveal an inner spiritual depth. He said he has almost given up painting with a brush, noting, “you should be able to paint with a stick,” though he prefers a palette knife.

As the exhibit progresses, animals become more prominent, finally exploding in the last gallery with dynamic paintings of birds, including a magnificent Raven with the brooding intensity of a religious icon on a monumental scale more usually associated with contemporary realism. But seagulls are the main attraction, culminating in a series of misbehaving laughing gulls inspired by the Seven Deadly Sins. Wyeth’s gull paintings are much looser and freer than his earlier work, even containing splashes of color with the wild abandon of an abstract expressionist.

-—DAN R GODDARD