A multipotentialite, according to Emily Wapnick, is “a person with many interests and creative pursuits.” Another word for this multifaceted creator is a polymath, defined as a “person of wide-ranging knowledge or learning.” The Greek word polymathes actually means “having learned much;” poly “much,” and manthanein translates to “learn.”

Leonardo Da Vinci comes to mind; at once a talented painter, sculptor, mathematician, scientist, inventor, he had a wide range of knowledge on many subjects. Such individuals are sometimes called “renaissance people” as the work that they produce is usually associated with ushering in a new age.

In October of 2020, the Buffalo Bayou Partnership celebrated its 5th anniversary with an “Artful Anniversary” series featuring five unique virtual performances. Urban Souls performed Take Me To The Water, Guy’s work based on his “bone” memories of his own baptism, which reflects his many streams of genius.

In this work, Guy resourcefully utilizes every space within The Cistern to explore the concept of baptism.

Baptism is seen in the Black church as an adoption into a new relationship with God, a deeper connection with the community and an embracing of new life. The differential advantage that Urban Souls offers is that, in addition to technically sound talent and beautiful strong bodies, its dancers bring the emotional energy of their own experiences to express the reverence of this water ritual. In the vastness of the Cistern space, curated lighting illuminates the shapes and the passion of every movement.

Each movement is accompanied by a tapestry of sound; Guy reading sacred passages to mark each moment of the spiritual journey, African drums and rich live singing, poetry, sounds of water, wind, breath, and the voices of the dancers as their powerful words reverberate. Even the Cistern becomes an instrument in this performance.

As the piece carries us from moment to moment, we are assured by Guy’s steady voice: “And this water symbolizes baptism that now saves you also, not by the removal of dirt from your body, but the pledge of a clear conscience toward God…”

When the Cynthia Woods Center for the Arts came calling in 2020, he was ready to transform the theater into a space that connects hearts, worlds and mindsets. A curator of Ten Tiny Dances in 2018, he shifted the narrative and the gaze toward the change that he wants to see. “Artists create with the misfortune of being triggered and not healed. Artists are creating and producing work that heals others,” Guy shares. “I have felt invisible in this realm.” In his self-choreographed and performed “Mr. Invisible,” his nuanced movements explore the waves of anger, fear and despair that many Black artists feel when their well-done work goes ignored by the mainstream media.

It’s a feeling that he knows all too well. In his Racism and the Arts training, Harrison shares that since founding Urban Souls, he worked for 16 years with very few grants, invitations or media coverage from a non-black organization. “I spent a lot of years begging and courting to get people to believe in the work that we do. I knew that it was not just for Black people to see.” Guy pauses, in reflection. “And that in fact, if non-Black people saw it, they would get more out of it. Black people already know about racism.”

A trip to Rwanda was a revelation and a motivation. Guy had traveled with the assumption that he had something to give; he returned having experienced a different kind of baptism. His immersion in a culture in which African features were normal and one that did not espouse Western and European beauty ideals as the standard invigorated him.

“I began to think about how free I felt; my shoulders were down. I felt like I was at home,” he recalls. “At home you can just recreate yourself over and over again, and I wondered why haven’t I felt like this before?”

Being welcomed and adopted by those he met was an invitation into a new way of seeing, and a new way of understanding how he was seen.

“In Rwanda, I learned that what I have is good enough and there is no need to convince people or to spend my time creating work with a convincing mechanism to it. I am so happy to have this awareness. After that trip, if you follow the work, it was where I just created anew; I was like, “Let’s just go create anywhere.’ ” His journey was not just an invitation to see his skin differently; it was a challenge to be in his skin, gloriously.

Upon his return, he became more deliberate about the convergence of dance and human rights.

1 ⁄7

Harrison Guy, director and choreographer of Black Bodies in White Spaces at The Moody Center for the Arts in collaboration with the Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning. Photo by Rory K James.

2 ⁄7

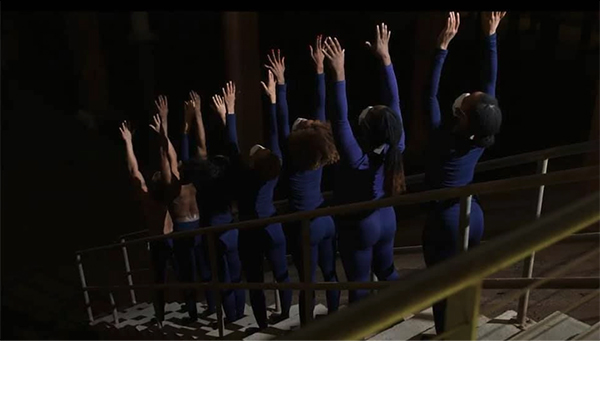

Urban Souls Dance Company at the Glassell School. Photo by Shoccara Marcus.

3 ⁄7

Urban Souls in Harrison Guy’s Take Me to the Water at Buffalo Bayou’s Cistern.

4 ⁄7

Jason Dennis and Courtney Sherman-Allen.

5 ⁄7

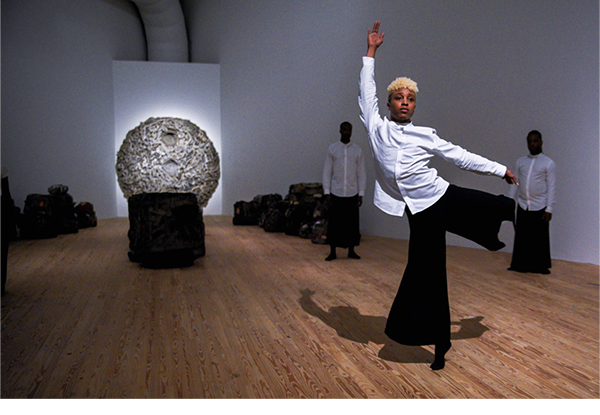

Cameo Miller in Harrison Guy’s Black Bodies in White Spaces at the Moody Center for the Arts.

6 ⁄7

Jaylon Givan, Toba Atkins-Montana, and Hindolo Bongay in Harrison Guy’s ReWritten in Stone as part of CAMH’s Ideas on the 28th Amendment, Nari Ward We the People' exhibit. Photo by Sanjuana Banda.

7 ⁄7

Jaylon Givan, Cameo Miller, and Jem the Poet in Black Bodies in White Spaces at The Moody Center for the Arts in collaboration with the Center for Engaged Research and Collaborative Learning. Photo by Rory K James.

In February of 2020, when we were still able to experience performances in-person and sans masks, he was the first Center for Engaged Research and Collaborate Learning (CERCL) Artist in Residence at Rice University’s Moody Center for the Arts. During Moody’s spring exhibition, “Radical Revisionists: Contemporary African Artists Confronting Past and Present,” Guy choreographed and presented “Black Bodies in White Spaces.”

“My perspective is not ‘Let us in these white spaces as a resume builder,’ but rather, ‘How do we reimagine what they could be?’ ” Guy shares.

When William Marsh Rice bequeathed his fortune to establish Rice University, he did so with a cruel and specific condition: that Rice University was for white students only. In the 1960s, The University sued the Rice estate in order to allow students of every race to attend. Harrison’s work began outside with a reconsecrating ritual. He then led participants through the exhibition spaces and finally the theater. His intention was to touch and to fill every space within the space. He shifted the energy of the Moody Center with this act of sacred inclusivity.

He thinks of this and his recent work with Urban Souls at the Contemporary Arts Museum of Houston, Re/Written in Stone: Ideas on the 28th Amendment. The work begins with a reading of “Let America Be America Again” by poet and activist Langston Hughes.

Guy is clear: “The work is not saying, ‘Let us in these spaces.’ It’s saying we will transform these spaces going forward. Our presence is a baptism of the space. We’re not happy to be here; we’re happy that you get to experience us being here.”

Including diverse and immensely talented artists doesn’t erase the past; it creates a hopeful, sustainable and authentic future. Guy believes that organizations broaden their audiences by creating a safe space for Black bodies. “That signals to other oppressed groups that you may be good with them.” He says. “People from the LGTBQIA community are looking for a cue to inclusion. If you are good on race, and you got it right on race, you might get it right including other communities.”

Harrison’s eyes flicker at the mention of his award from Society for the Performing Arts for his new piece, entitled Colored Carnegie. This work explores the locally and nationally-historic story of the Black committee who worked to open the first African-American Library in Houston, funded by Andrew Carnegie and guided by Julia B. Ideson, for whom the most ornate section of the Houston Central Public Library is named. After Houston denied library service to its African American citizens, Colored Carnegie would garner support from Booker T. Washington and stand in Houston for over fifty years.

“There will always be a theme of Black history. It’s still a big part of the work and that’s because I love history.” Harrison declares. “But it’s not from a teaching standpoint. It’s really from a perspective of honoring; there is a different energy when you are working to honor a story. It feels good to me.”

He grins thinking about the beauty of this story, on that stage. “It has a lot for a lot of people.”

As if this wasn’t enough, and it really is, Guy also teaches the next generation of dancers at Houston’s Kinder High School for Performing and Visual Arts. His class, called “The Skin I’m In,” is an intersection of the arts and the humanities. ”In the class, we talk about identity, empathy, true history and how this is connected to your art.” Guy noticed that the students could technically do anything, yet they were not being taught to connect their soul to their craft. “I am able to walk the students through real-life empathy and put themselves in the shoes of those who are different from them.” When asked how the students responded to such a daring effort, he shares, “They had never been in a space that was so safe, and they were really grateful for this space. They told me,’“We feel like we are the experts in the room.”’

He will continue to teach and has even adapted the curriculum for the students at Henderson Elementary.

As the first African American gay man Grand Marshall of Houston’s Pride Parade and a leader on Mayor Turner’s LGBTQ Advisory Board, Guy’s eye is on creating a path of support and education for the emerging classes of dancers and community leaders.

With his calendar and his heart full, Guy shares “I am really excited about my artistic path. I am more excited about what I’ve gotten to do than what I’ve gotten.” When it comes to striving, pleading, and appealing to the white gaze, Guy responds:”If people like it, they like it. Either they like it or they don’t. I’m at the point in my career where proving is not a part of the work for me anymore.”

Harrison’s hope and work is that more spaces will open their doors to the baptism and transformation that happens when its inhabitants are truly free.

—DANIELLE FANFAIR