“What I’m trying to work with and understand is what makes a sonic territory fertile, and how it affects culture,” says Houston-based multidisciplinary artist Jamal Cyrus. His is a journey in step with music that evolves out of a specific place.

A focus of Cyrus’s broad and layered visual art practice is to uncover legacies of Black music and its makers in American culture. “Looking back, my work has always been part of a process of self-education” he says, noting the gaps—often, outright erasure—that results from the lack of teaching about these lives and stories.

“Due to the illegality of teaching the enslaved to read and write, and the subsequent lack of access to education following Emancipation and well into the middle of the 20th century, the action of teaching oneself has a long history within Black culture. This concept, is of course, multidisciplinary, appending itself through practical, political, and spiritual import,” he said on the occasion of receiving a Joan Mitchell Painters & Sculptors Grant in 2019. He has also received the prestigious Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award and the 2020 David C. Driskell Prize.

When Cyrus was in graduate school, Terry Adkins, one of his mentors, gave him an iPod which contained The Collected Poem for Blind Lemon Jefferson, an album from 1971 by experimental jazz composer and saxophone player Julius Hemphill and poet K. Curtis Lyle that mythologized the life of Blind Lemon Jefferson—a listening experience that became the impetus for the works on view at The Modern.

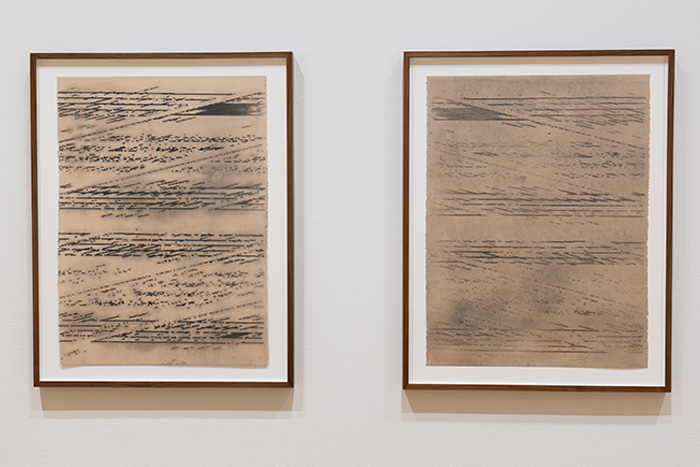

For example, Cyrus has created text-based drawings in graphite powder by borrowing from an ornithologist manual on translating bird sounds into English sounds, which he then translates into a saxophone solo. He tells me that both Hemphill and Ornette Coleman were inspired by saxophonist Charlie Parker, and they first heard his music on jukeboxes in Fort Worth, and Parker’s nickname was Yardbird.

“In regards to sound and music, I’m most interested in their uses outside the realm of entertainment,” says Cyrus. “In America, music has been used to create communities. It’s been used to integrate American society and it’s been used as a tool to politically organize and educate.”

1 ⁄6

Jamal Cyrus

Common Tongue, 2022

Denim, piano keys, and cotton thread

Overall: 55 × 43 in. (139.7 × 109.22 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago 60.2022.10

2 ⁄6

Jamal Cyrus

Port of Call, 2022

Conch shell, microphone stand, microphone wire, caulk, and vinyl Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago 60.2022.3

3⁄ 6

Jamal Cyrus

River Bends to Gulf (Double Time), 2021

Denim and cotton thread

Overall: 73 × 110 1/2 in. (185.42 × 280.67 cm)

Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago 60.2022.1

4 ⁄6

FOCUS: Jamal Cyrus at The Modern April 1, 2022 - June 26, 2022, installation image.

5 ⁄6

Jamal Cyrus

(left) Rite_1-Percussion Ballad, 2022.

(right) Rite_1-Percussion Ballad (reverse low pass gate), 2022. Graphite powder on paper. Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago.

6 ⁄6

FOCUS: Jamal Cyrus at The Modern April 1, 2022 - June 26, 2022, installation image.

Later on he learned that the type of indigo, the color used to dye blue jeans and grown in the southern US and southeastern US, was essentially cultivated in West Africa. He also learned that denim was one of a few types of cloth relegated to enslaved blacks in the American South.

Cyrus also cites Gee’s Bend quilts as a point of inspiration and connection. Several years ago when he saw a small show of the quilts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, he was drawn to the numerous lines throughout the fabrics. His fascination with the use of multiple or accumulated lines literally and figuratively connects works in which he glues together ironed strips of denim. The result is a visual rhythm of masses of threads that refer to alluvium, organic deposits left by flowing streams in a river valley or delta, typically producing fertile soil: A fitting metaphor for the blues.

—NANCY ZASTUDIL